|

The Rise of the Nazi Party, 1928 — 33 |

Economic and Political crisis following the World Depression |

|

October 1929 marks a turning point in the History of Germany during the inter-war period. During this month Gustav Stresemann, also died. It is usual to regard Stresemann as a strong leader who might have saved democracy in Germany had he lived, so his death is significant. In the same month there was the Wall Street crash.

|

|

|

These events precipitated a crisis in the Germany, but the crisis was already rooted in the weaknesses of the Germany economy prior to 1929. (1) There was nothing substantial about the German boom of 1924-9, since it was fuelled by short-term borrowing from the United States at high rates of interest. (2) Agriculture in Germany was also in recession. There was world over-supply, and this had caused a decline in world agricultural prices by 30% from 1925 to 1929. Rents on agricultural land in Germany were high. (3) The German middle class (The Mittelstand) was also feeling the pinch; as a class it was squeezed between the power of large-scale industries on the one hand, and the mass trade unions on the other. (4) In 1928 there was already a significant slow-down in economic growth; unemployment had risen to 1.3 million.

|

|

|

The First World war had contributed to the long-term instability of Germany. It shifted the balance of power from Europe in favour of the United States. The United States had become the major creditor nation. Between 1913 and 1929 there was a boom in the American economy which grew 70% during this period. In the same period there was only 4% growth in Germany. American people speculated without restraint, buying shares without funds to support the purchase and anticipating rising share prices. The American economy was a bubble. In an atmosphere of doubt major shareholders sold out in October 1929, precipitating a crisis that led to the Wall Street Crash of 24th October 1929 (Black Thursday). Germany was particularly vulnerable to the consequences of this crash. There was a decline of world demand, and prices and wages fell. Unemployment in Germany climbed during the winter of 1929-30 to over 2 million. By October 1930 it reached 3 million; it was 5.1 million in September 1932, and it peaked in the early months of 1933 at 6.1 million. These figures also underestimate the impact of the depression in Germany, since people who did not register as unemployed are not included in them. Social benefits were paltry, and virtually every class was affected. There was the loss of respectability that also went with unemployment. There was particularly strong agricultural poverty. The effects gave the appearance that there was an uncontrollable breakdown of society. In this climate people lost faith in the democratic processes of the Weimar republic and started to turn to forms of political extremism for answers.

|

|

|

The election of May 1928 had brought to power a coalition government under the leadership of Hermann Müller, leader of the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

|

|

|

Although the overall result of the May 1928 election was poor for the Nazis, in some respects their electoral position was better than overall appearances. In rural areas, where agricultural depression had already started, the party won over 10% of the vote. During 1929 the political issues were those of the Young plan and the subsequent referendum organised by Hugenberg. As a result the Nazi were given access to Hugenberg's media empire, and the association with Hugenberg gave the Nazis the appearance of respectability. Leading industrialists made financial donations to the party — the chief among these were Emil Kirdorf, the leading coal magnate in the Rhur, and Fritz Thyssen, the steel manufacturer. Membership of the NSDAP during 1929 increased to 178,000 and the Nazis won further support in the state elections. They polled 11.3 % in Thuringia, and a Nazi party member, Wilhelm Frick, became a minister in the state government.

|

|

|

Following the May 1928 election, there was still the issue of reparations. The Dawes Plan of 1924 had rescheduled payments, but this had been only a temporary measure. The Inter-Allied Reparations Commission, headed by American banker Young, reported in June 1929. It proposed a “permanent” solution by reducing the overall sum to £1.85 bn and rescheduling repayments to last until 1988. In return for accepting the Young plan Streseman had obtained a promise that the allies would evacuate the Rhineland by June 1930.

|

|

|

Right-wing parties within Germany regarded the acceptance of the Young plan as a further betrayal of Germany. Alfred Hugenberg, a media tycoon who owned 150 newspapers, a publishing house and the UFA film company, and was the leader of the Nationalists organised opposition to the treaty. He was supported by other right-wing groups such as the Pan-German League and the Nazis. They denounced the payment of reparations in their Law against the Enslavement of the German People. This was supported by enough signatures to force the government to concede a referendum over the issue, which took place in December 1929. The opposition to the treaty was defeated, securing only 5.8 million votes instead of the 21 million it required. However, one effect of the whole episode was to increase the apparent respectability of Hitler and the Nazi party and to publicise their cause.

|

|

|

Chancellor Müller found it increasingly difficult to hold the government together. The German People's Party, following the death of Stresemann, who was its leader, drifted to the right. The increase in unemployment created a deficit in the insurance scheme. Social Democrats wanted increase welfare payments, but this was opposed by the People's Party. The government was split over the issue and Müller was forced to resign as a consequence. President Hindenburg appointed the leader of the Centre party, Henrich Brüning as the new Chancellor. But this was not an appointment of a democratic leader, but the result of intrigue between various influential people connected with the President. The principle agents of this move were Otto Meissner, who was the State Secretary to the President, Oskar von Hindenburg, the son of the President, and General Kurt von Schleicher, the political leader of the army. These people had lost faith in democracy, and conspired to create a strong centralised authoritarian government. Brüning proposed cuts in government expenditure, which were rejected by the Reichstag by 256 votes to 193 in July 1930. The proposals were implemented nonetheless by Presidential decree. This was opposed by the Reichstag which voted for a withdrawal of the decree. At Brüning's request Hindenburg dissolved the Reichstag and an election was called for September 1930.

|

|

|

The depression of the 1930s increased the popularity of the Nazi party, and in September 1930 they gained 107 seats in the Reichstag as a result of the election. Support for the Nationalists and middle-class democratic parties declined at the same time. Turn out at the election had increased from 76.5 to 82 %, and the electorate was also larger by 1.8 million voters; some of the Nazi support came from first-time voters and people not used to exercising their right to vote. At the same time the Communist Party increased its share of the vote to 14.3%, and gained 23 new seats in the Reichstag.

|

|

Semi-dictatorship

|

|

|

The election of September 1930 placed the chancellor Brüning in a more difficult position, since his government was now opposed by more powerful extremist groups on both the right and the left. He was not, however, forced out of office, since Hindenburg still exercised his power of presidential decree in his favour. Additionally, the Social Democrats decided to give tacit support to this arrangement, since they were more alarmed by the growth of the extremist parties. Brüning adopted deflationary economic policies in order to prove to the Allies that Germany was no longer capable of paying reparations, and reparations were abolished at the Lausanne Conference in June 1932. Brüning also attempted to negotiate a customs union with Austria, but following the announcement of the scheme in March 1931 the French opposed it; it was referred to the International Court of Justice which narrowly ruled that it was contrary to the Versailles Treaty. As a result the foreign minister Curtius resigned.

|

|

|

A financial crisis ensued within Germany. The Danat, one of the major banks, was forced to close in June 1931, and at the same time unemployment increased to 5 million by early 1932. Brüning helped to secure the re-election of President Hindenburg when the presidential election fell due in spring 1932. Hindenburg was opposed by Hitler and the Communist, Thälmann; Hindenburg polled 19.3 million votes (53%) to Hitler's 13.4 million (36.8%) and Thälmann's 3.7 million (10.2%)

|

|

|

Despite the support he received from Brüning during the election, Hindenburg forced the Chancellor to resign in May 1932 by refusing to sign any further decrees. Brüning was proposing to employ 600,000 unemployed on Junker estates in East Prussia, and the unpopularity of this scheme gave Schleicher the opportunity to bring about Brüning's downfall.

|

|

|

Brüning was replaced as Chancellor by Franz von Papen. Von Papen was a Catholic aristocrat and a member of the Centre Party and a close friend of Hindenburg, but he lacked political experience and was not a member of the Reichstag. Schleicher intended to use von Papen as a puppet. In order to gain the support of the Nazis von Papen agreed with them to dissolve the Reichstag and call a fresh election, and also to lift the government ban on the SA and SS. The election was scheduled for 31st July 1932, and was fought amidst unprecedented street violence. At the same time Scheicher and von Papen abolished the Prussian state government on the pretext that it was ineffective. Von Papen declared a state of emergency in Prussia and made himself Reich Commissioner of Prussia. Despite this undemocratic act the Social Democrats and trades unions staged no kind of effective protest. The election gave the Nazis a dramatically increased share of the vote — rising to 13.7 million votes and 230 seats. In fact, Hitler was constitutionally empowered to form a government.

|

|

|

|

|

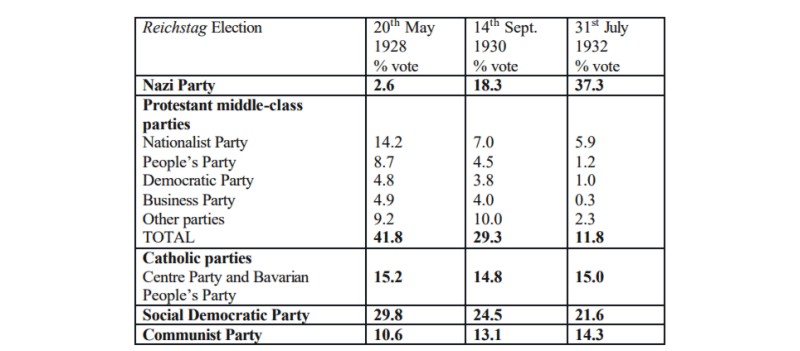

German elections 1928 — 1932

|

|

The Basis of Nazi Political Support |

|

By 1932 the Nazi party had become a national movement attracting support from many different groups. The statistics for the voting in the elections indicate that the Nazis won support at the expense of primarily protestant middle-class parties and to a lesser extent the Social Democrats. The Catholic parties and the Communists did not lose support during this period. The Nazis had more support in the north and east of Germany, and less in the south and west. This was owing to the strength of Catholic support in the south and west; the more Protestant the region, the more significant were the Nazi gains. Whilst Bavaria was the birthplace of Nazism, it had the lowest percentage of Nazi supporters at this time owing to the strength of Catholicism there. Whilst the Nazi party had started as a “workers” party, by this time only 32.5% of its support derived from workers; it drew support from Protestant, rural and middle-class people.

|

|

|

The resilience of Catholicism and socialism to the Nazi advance can be accounted for by (1) the fact that both Catholicism and socialism were coherent ideologies opposed to Nazism on an intellectual level; (2) both had well-developed organisations.

|

|

|

Those voters who turned to Nazism had lost faith in the existing system, and felt that their traditional status was threatened. Seymour Lipset has proposed the theory that fascism is a middle-class reaction to perceived social threat. The Nazis presented themselves as revolutionary and reactionary at the same time. They suggested that they were going to return Germany to some former glorious age. Hitler exploited middle-class anxiety with the promise of a solution to the current economic crisis and a return to respectability.

|

|

|

Additionally, the depression coincided with a demographic bulge in the population owing to a pre-war increase in babies. This meant that there was disproportionately higher unemployment among the young and new entrants to the labour market, and the Nazis derived considerable support from this class. 41.3% of party members before 1933 were born between 1904 and 1913.

|

|

|

The Nazis were not the only extreme right-wing party in Germany during the inter-war period. However, they were different from other groups primarily in their grasp of the importance of propaganda. Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf that “the receptive powers of the masses are very restricted, and their understanding is feeble ... all effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare essentials”. Joseph Goebbels was placed in charge of propaganda in April 1930. The Nazis made extensive use of posters and leaflets; they made use of all forms of media: loudspeakers, radio, film and records. Hitler was very active and combined the apparent ability to be everywhere with a statesmanlike image. Mass rallies were organised; an intense emotional experience was generated by means of flags, uniforms, torches, salutes, music, songs and anthems. Messages were adapted to the different audiences.

|

|

|

The Nazis made systematic use of violence. For example, during July 1932 there were 461 riots in Prussia and street battles between Communists and Nazis were a regular occurrence. In one incident alone there were 19 deaths when Nazis marched through a working class district in Hamburg.

|

|

The Appointment of Hitler as Chancellor |

|

Following the July 1932 election, Hitler aimed to become Chancellor, which neither Schleicher nor von Papen were prepared to accept, and a meeting between Hitler, von Papen and Hindenburg on 13th August produced no resolution to the problem. Von Papen expected Nazi support to decline in the atmosphere of political deadlock, and he dissolved the Reichstag on 12th September and called another election. The Nazis were short of funds, and were unable to fight so effective a campaign and their support fell to 11.7 million votes (33.1%), giving them 196 seats. However, von Papen still did not have a majority supporting him in the Reichstag. Von Papen sought to persuade the President to declare martial law and establish a presidential dictatorship, but Schleicher would not support von Papen, and Hindenburg requested von Papen's resignation. Schleicher himself sought to establish a government by splitting the Nazi party, gaining the support of the socialist faction of the party under Gregor Strasser. Strasser was willing to accept Schleicher's offer, but Hitler successfully isolated Strasser within the party. Von Papen now sought to regain office by negotiating with Hitler and persuading Hindenburg to accept Hitler as Chancellor. Hindenburg was encouraged to accept this offer by his son Oskar and State Secretary Meissner, and on 28th January Hindenburg withdrew support from Schleicher and Hitler was appointed Chancellor on 30th January 1933 with von Papen as Vice-Chancellor.

|

|

Why did the Nazis Replace the Weimar Republic? |

|

(1) There was a general collapse of popular support within Germany for the Republic; in 1932 only 43% of the electorate voted for pro-republican parties. (2) The Depression profoundly destablised Germany politics and gave the Nazis an opportunity to exploit the crisis as a manifestation of the failure of the Weimar Republic. (3) The Nazi “ideology” of racism, nationalism and anti-democratic ideas was actually appealing to a large class of disillusioned middle-class people. (4) The Nazis made successful use of propaganda techniques. (5) Hitler was a charismatic leader with astute political cunning. (6) Leaders in the army, the landowning class, and the industrial class came to accept that they needed to do a deal with Hitler and cooperated in his appointment as Chancellor in 1933. It appeared to them that the alternative to Hitler was a military dictatorship, and this could be followed by a civil war. Therefore, a deal with the extreme right appeared attractive as a means to crushing the left and stabilising German politics.

|

|

|

Hitler's first cabinet included Papen, Hugenberg and von Blomberg — conservative politicians that enhanced the apparent respectability of the government. The conservative parties believed that Hitler could be controlled.

|

|