|

The Economics of the Third Reich |

|

Before 1932 Hitler had no real economic policy to speak of. From 1932 onwards the Nazis started to address this issue. (1) They wanted Germany to become an autarky (a self-sufficient state), and then develop into the dominating economic power in Europe. (2) They accepted the idea of deficit financing as a means to creating jobs and expanding demand. (3) They wanted Germany to develop an economy that was devoted to the needs of war even in peace time. However, there was no overall plan in January 1933 and Hitler was wholly uninterested in economic issues. The lack of consistency in their subsequent policies indicates that policy was made up on an ad hoc basis — that is, in response to situations as they arose.

|

|

|

During the period from 1934 to 1937 Nazi economic policy was directed by Hjalmar Schacht, who was President of the Reichsbank from 1933 to 1939 and Minister of Economics from 1935 to 1937. Schacht had played an important role in the establishment of the new Germany currency in the wake of the hyperinflation criss of 1923. During the 1934 to 1937 he directed the government expenditure programme on such things as public buildings, armaments and motorways. The Nazi period coincided with a period of growth in the world economy, but the reduction in unemployment within Germany to 1.7 million by mid 1935 was an impressive achievement.

|

|

|

Germany started to import more in raw materials than the value of its exports, and a balance of payments problem began to develop. To combat this the government introduced strict controls over wages and prices, which was possible owing to the abolition of trades unions. However, the balance of payments problem continued to worsen during 1934.

|

|

|

Economics Minister Schmidt advocated an increase in public consumption, but the Nazis wanted a rearmaments programme. The upshot was that Schmidt was dismissed and Schacht was appointed as both Economics Minister and President of the Reichsbank. He was given, by a law of 3rd July 1934, power to control all aspects of the German economy and currency exchange. From 1934 Germany pursued a policy of signing bilateral trade agreements with other countries, especially in the Balkans and South America. This extended German influence in these areas.

|

|

|

The trade agreements solved the balance of payments problems, and by the end of 1935 there was a trade surplus. During the period 1933 — 35 the economy had grown by 49.5%. However, the apparent success of the policies concealed structural weaknesses in the economy — a point which Schacht himself recognised. Further pressure on Germany's balance of payments continued. In order to redress the problem, Schacht proposed a reduction in armaments expenditure, but the Nazi leadership would not countenance this, and Schacht's prestige was diminished as a result.

|

|

|

In 1936 a Four-Year Plan was introduced by Göring aiming to make Germany ready for war. Schacht's influence was very much reduced, while the Nazis moved towards establishing an even tighter control on industry, whilst maintaining regulation of imports and exports. They aimed to be self sufficient in all raw materials, and to develop synthetic substitutes for those raw materials they did not have direct access to. Schacht resigned in November 1937 and was replaced by Walter Funk, but Göring became the real economic dictator. The plan had a mixed result. Germany did not succeed in eliminating reliance on all imports, but it did expand production of such things as aluminium and explosives.

|

|

|

One intentionalist theorist, B.H. Klein, has argued that the strategy of short wars that would not overburden the economy was a deliberate policy of the Nazis, and that the Nazis did not turn Germany into a war economy until after the Stalingrad defeat of 1942-43. Milward has modified this theory, but basically agrees that the policy of Blitzkreig was not intended to develop into a war of attrition. He places the turning point in Nazi economic thinking, however, earlier — after the failure to take Moscow in 1941.

|

|

|

However, political historians have concluded that the outset of the European war in 1939 was not part of a German policy. Hitler expected the war with Poland to be a short, local war and that Britain and France would not be involved. According to Overy Hitler was preparing for a total war, but only to commence in 1943. From this perspective the declaration by Britain and France of war on Germany in 1939 stalled the Nazi plans to create a superstate, and forced them into the policy of Blitzkrieg.

|

|

|

Nonetheless, during the period 1936 to 1939 two thirds of all German new investment went into the rearmaments programme.

|

|

|

Industry did boom under Hitler. The abolition of the trades unions encouraged capital investment. However, small businesses did not prosper — it was bigger business that did well. The first industries to expand were the coal and steel industries, thereafter, the electro-chemicals industries did very well.

|

|

|

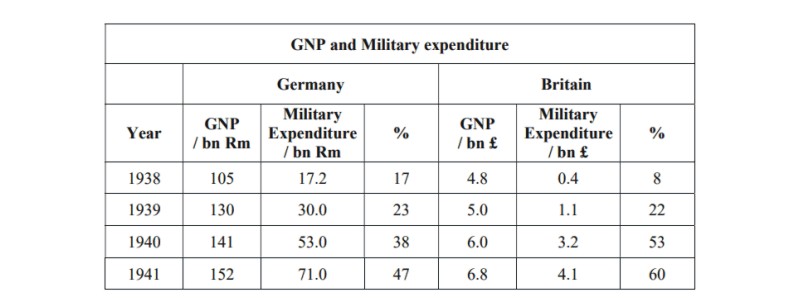

The military successes of 1939 — 41 enabled the Germans to hide many of their ongoing structural weaknesses. In fact, the British were more successful in mobilising their economy for war than the Germans.

|

|

|

At some point the Nazis started to address the weaknesses in their economy, but historians have not been able to identify exactly when this happened. For instance, reforms were introduced by Albert Speer as Minister of Armaments from February 1942, but some of those reforms were already initiated by Fritz Todt, who was his predecessor.

|

|

|

|

|

The main initiative introduced by Todt and Speer was to relax the controls on industry. They replaced rigid controls with a committee called the Central Planning Board. This committee regulated sub-committees each of which had responsibility for some sector of the economy. Speer was able through this committee system to maintain central control of the economy, whilst still allowing industry freedom to take their own initiatives.

|

|

|

German industry remained broadly loyal to the Nazis throughout the period, even when Germany was facing immanent defeat towards the end of 1944. Industrialists appear to have been satisfied with the continuing rise in profits.

|

|