|

The Social and Economic Developments of Russia during the later Imperial Era, 1881 — 1914 |

The Social and Economic Structure of Tsarist Russia |

|

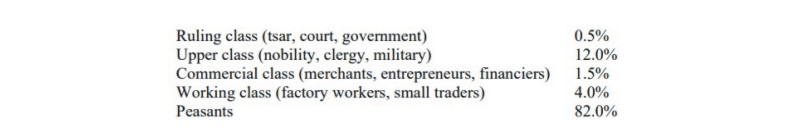

The 1897 census indicated:

|

|

|

|

|

1897 census

|

|

|

Over 80% of the population were peasants, and they were mainly illiterate. The ruling elite both feared and despised them, and denied them free expression.

|

|

|

Russian was officially divided into estates (sosloviya), but it is now thought that a rigid caste system did not exist and some mobility between the estates was possible. The aristocracy stood at the pinnacle of Russian society. In 1900 there were 79 aristocratic families owning land of about 46,000 hectares each. Such families tended to concentrate of raising livestock and forestry. They often possessed large areas of timber land in the Urals. Such families would also own urban property and securities. The aristocrats were enormously wealthy.

|

|

|

The provincial gentry were squeezed, and were the objects of envy of the peasants. For example, during the 1905-6 revolution peasants often destroyed the products of their enterprise, such as vineyards, livestock and machinery. This provoked a reaction from the gentry from 1907 onwards, and they politically were opposed to reforms.

|

|

|

The lower commercial classes were made up of office staff, shopworkers and artisans. They were active in the period of 1905-6 in campaigning for higher wages and better conditions. The craft industry produced a large variety of goods. However, artisans were desperately poor.

|

|

|

Thus Russian society had many horizontal divisions as well as vertical ones based on nationality. The horizontal divisions may be linked to the strong prevalence of class antagonism that existed even during periods of domestic peace. Life for workers and peasants was permeated with violence, such as fist-fights, gang warfare and lawless behaviour. This violent mood also found expression in the form of anti-Jewish pogroms.

|

|

|

Nonetheless, class antagonism was countered to an extent to the existence of monarchist sentiment. The tsar was still respected, particularly among peasants, as a semi-divine being. Peasants were more likely to become politically agitated in those regions where there was the highest population density. Peasants who joined the army often acted as vehicles for disseminating revolutionary ideas into villages.

|

|

|

The population of the Russian empire rose from 74 million in 1860/64 to 164 million in 1909/13. The birth-rate remained steady but the death-rate decreased from 37 per 1000 in the 1860 to 27 in 1000 by 1914. This was due to better nutrition than to better medical care.

|

|

|

Russians tended to marry young and have, on average, nine children half of which died young. There was strong community pressure to maintain this traditional lifestyle. Those who migrated to town, or who rose in social status, tended to have fewer children.

|

|

|

There were changes to the structure of the typical Russian family. For example, a study of a Voronezh province in 1887-96 showed that 42% of households comprised two generations and 46% three or more, but it seems that the proportion of families with three or more generations was declining. This was a patriarchal system, but women did have a well-defined economic and social role, and were valued. Nonetheless, women were often the recipients of violent beatings from their husbands, and many young country girls were not attracted to the prospect of marriage, and preferred to work in textile mills or take up domestic service.

|

|

|

The bulk of the lower ranks of the army and navy were conscripts. Army life was brutal - discipline severe and conditions grim. Between 1825 and 1855 1 million Russians died whilst in the army during peace. The C19th peacetime strength was 1.5m. It cost the government 45% of its annual expenditure, whilst 4% went on education. Only aristocrats could occupy the higher ranks and there was widespread corruption. Except for the Crimean war, the army's primary duty was the suppression of national risings.

|

|

|

By the C19th the bureaucracy was corrupt and incompetent, but it had immense power over the lives of the people. It was regarded as a scandal.

|

|

Autocracy |

|

The Romanov dynasty had been Tsars since 1613. They believed in their divine authority and were autocrats. The Imperial Council, the Tsar's advisory committee, and the Cabinet were appointed by the Tsar. They had no power to oppose the Tsar. Thus Russia was politically backward, with no parliament and no official toleration of political parties. There was state censorship. All opposition had to be covert and the Tsar's secret police, the Okhrama, often infiltrated left-wing groups.

|

|

|

It has been maintained that political opinion in the ruling elite was divided between 'Westerner' advocating adoption of Western European style political institutions, and 'Slavophiles' who rejected Western values. Reform was prevented by the absence of representative institutions. The tsars were not prepared to yield power and reforms in Russia came about only in response to some shock to the system. Alexander II (1855 - 1881) did introduce some reforms. In 1861 there was the emancipation of the serfs; in 1864 there was the creation of rural councils (zemstra) which were elected, even if the franchise made them dominated by the rural gentry. Village communes (mir) were also given administrative functions and there were legal reforms. Alexander II permitted greater freedom of expression and a Russian 'intelligentsia' developed. He wanted reform from above rather than revolution from below. But Alexander II remained an autocrat and during the 1870s he swung back to the right.

|

|

|

The orthodox church supported the tsars. The church had been outside papal authority since the C15th. Its catechism included the statement, “God commands us to love and obey from the inmost recesses of our heart every authority, and particularly the tsar.”

|

|

Agriculture and Peasantry |

|

The edicts of 1861-6 freed peasants from serfdom but did not make them prosperous. The lack of material progress is linked to the adherence to Russian traditional crop rotation system, which persisted right up to the 1917 revolution. Methods were primitive — the use of the wooden plough, for example, persisted. The continuance of village communes (obshchina) fostered egalitarian sentiment. These communes periodically redistributed land according to changing family needs. The quality of peasant housing remained poor, and standards of hygiene were poor. One result of this was a terrible cholera epidemic in south and south-east European Russia following the famine of 1891-2. Several hundred thousand people died. Peasants were generally illiterate, poverty-stricken and angry.

|

|

|

The best arable land was in the Black Earth region - the part of European Russia that stretches from the Ukraine to Kazakhstan. Demand for land exceeded supply and although peasants could buy land, its price was too high for them. The government also taxed property sales as a means of compensating landowners for losses incurred by the emancipation. Peasants that did buy had heavy mortgage payments and their holdings were very small. Modern equipment was not used.

|

|

|

However, this is the traditional description of Russian peasantry at this time, and since the 1960s there has been some modification of it. It is now recognised that some regions were not as backward as others. Peripheral areas, such as the Baltic states, the south-east and western Siberia, were more progressive than the Black-Earth region of south-central Russia. Russian peasant farmers had a more active role in the shape of their lives than has hitherto been recognised.

|

|

|

Yet it is true that the peasants were legally tied to their village communities and obliged to take the allotment given to them. They had to redeem the allotment by payments to the government who had in turn compensated the gentry for the loss of land. The period of redemption was set at 49 years. Many peasants fell into arrears and in 1882 the redemption dues were reduced, and in 1906 the whole system was abandoned.

|

|

|

The increasing population caused complaints about 'land shortage'. However, the average ex-serf had an allotment of 3.6 hectares and state peasants received 6.5 to 7.3 hectares.

|

|

|

The government believed that the obshchina was a means to maintaining order in the countryside. One way in which this was achieved was through the right of the village elder(s) to issue passports to peasants wishing to leave a village to work elsewhere. Nonetheless, the number of passports issued increased from 1.2 million in 1861 to 6.2 million in 1891 to 8.8 million by 1906.

|

|

|

It was not common for the obshchina to redistribute land from prosperous and innovative households to poorer ones. One way families increased the prominence and prosperity was to have large numbers of children. There was great social pressure on couples to produce male heirs. However, this means to increased status was temporary; once the children grew up they left the family and set up households of their own.

|

|

|

There was an increase in agricultural output. Total output for European Russia rose by between 1.5 and 1.9% per annum between 1860 and 1913. This was partly due to an increase in the area of land cultivated. Nonetheless, crop yields on peasant allotment land increased by 40% and on privately owned land by 63% during this period. The number of horses rose from 15.5 million in the 1860s to 21.4 million by 1914. The number of cattle rose from 21.0 to 30.7 million in the same period. By 1913 Russia was exporting over a million head of cattle per annum.

|

|

|

Thus food output increased in line with the population growth and people did not starve on the whole. So it is not true that villages became run down during this period; if anything prosperity increased. With the increase in cattle there was more manure available and this stimulated the development of improved systems of crop rotation. Peasants increased their ownership of land relative to the gentry. In 1877 the gentry owned 59% of the land, but by 1914 they owned 46%. There were many sales of land after the 1905-6 period of unrest with 12 million hectares being bought by peasants at that time. The gentry generally achieved higher yields that then peasants since they farmed less intensively.

|

|

|

The State opened a Peasant Land Bank in 1883, but it took two decades before it could make loans on an extensive scale. After 1895 capital was provided by credit cooperatives as well, yet there was a shortage of rural credit which inhibited agrarian development.

|

|

|

Leasing land was not an attractive option to peasants who could not afford to buy land, since rents were so high. As a result landless peasants often preferred to work as seasonal labourers on large estates in New Russia. The work was gruelling (sixteen hours a day) for minimal wages, but in 1900 2.5 million men worked in this way in New Russia alone.

|

|

|

Others attempted to migrate to Asiatic Russia. By 1908 3/4 million people crossed the Urals for this purpose, but the toil involved was such than many would give up and return.

|

|

|

Finally, surplus labour migrated to towns. For example, Moscow increased from 350,000 in 1856 to over 1 million inhabitants by 1897. There was also new industrial towns such as Ivanovo-Voznesensk. Conditions in the suburbs were insanitary, and there was considerable overcrowding, with, for example, 7.4 inhabitants per apartment in St. Petersburg in 1900, where, in 1914, 60,000 people were living in cellars. Peasants who migrated to towns tended to retain their links with their villages. In fact, workers remained officially peasants. Workers would regularly send money home to their villages, and return there themselves generally once a year to renew their passport and assist with the harvest.

|

|

Industry |

|

Generally, Russia was economically backward; and by 1880 an industrial revolution had not taken place. The Urals did have iron industries and textiles were manufactured in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Russia was too big and her road and rail network not sufficiently developed. There was no effective banking system.

|

|

|

The 1880s saw an industrial expansion in Russia. It has been called the 'great spurt'. Coal output from the Ukraine and oil from the Caucasus rapidly increased. The expansion was brought about by private enterprise. Government policy sustained it; however, for military reasons.

|

|

|

Sergei Witte was minister of finance from 1892 to 1903 and sought to modernise Russia. He invited foreign experts to advise on industrial development. He believed in state capitalism - that is, he expected the state to direct the development of the economy. He negotiated foreign loans of capital, but held high taxes and interest rates within Russia. Witte has been criticised for making Russia too dependent on foreign loans, and for not diverting resources to light industry and agriculture. Witte had many contemporary critics who were suspicious of him and his policies.

|

|

|

So industrialisation gathered pace during the period of Witte, who ensured that industrially was energetically supported by the state. The 1905-6 revolution interrupted this development, but thereafter there was a recovery and the period up to the 1914 war was a “second golden age” for Russian industry. However, nowadays it is held that state intervention to foster this development was not so important. Additionally, it would probably be a mistake to regard Russia as developing a capitalist mentality; Russia never developed an business ethos and free-enterprise economy. Typically, a Russian merchant of the Moscow region was ultra-conservative and came from an Old Believer family; they were concerned not to risk their position by political agitation. They were authoritarian and harsh in their treatment of workers, and tended to obstruct the efforts of government to introduce factory legislation.

|

|

|

The situation was more dynamic in the peripheral regions, especially in Russian Poland and the Baltic area, where St. Petersburg increased in population from 1.25 million in 1897 to 2.2 million by 1914. It was an important centre of metal-working, textile industry and food-processing. Newer industries of chemicals, rubber and electrical equipment also developed there. Much of this was due to foreign investment. Labour productivity increased. The Putilov works, manufacturing industrial machinery and railway locomotives employed over 12,000 men. Shipbuilding, leather-working and brewing were also important industries. There were also jobs in banking, insurance and the civil service.

|

|

|

In the south there was a major expansion in the iron and steel industry. This region produced 64% of the empire's iron and steel and 70% of its coal by 1913. Output of coal rose from 15.6 million tons in 1870 to 1.6 milliard tons by 1913. Firms organised into the Association of Southern Coal and Steel Producers, which was in effect a cartel that manipulated the market by making output quotas and fixing prices. This monopoly power was enhanced by the high degree of vertical integration in Russian industry — with corporations controlling every stage of production.

|

|

|

In the north Caucasus at Baku oil extraction became a major business financed by the firm of Nobel; yet Russian percentage of total world output fell as oilfields were opened up in the Near East and elsewhere.

|

|

|

Average gross factory output increased by 5 to 5.5% per annum during 1883 to 1913. Productivity increased by 1.8% during this period.

|

|

|

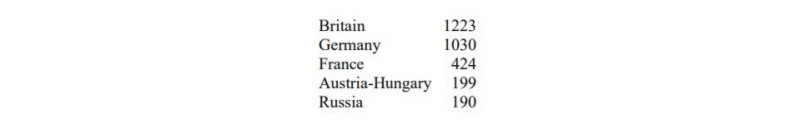

Comparative growth rates for 1894 — 1913 are:

|

|

|

|

|

Comparative growth rates, 1894 — 1913.

|

|

|

Foreign trade in £millions was:

|

|

|

|

|

Foreign trade, 1894 — 1913

|

|

|

Although Russian industrialisation was a success story, Russian industry was by no means firmly established by 1914, when the war struck. Historians debate whether Russia was or was not in a process of industrialisation in the period up to 1914. Alex Nove, the leading Western writer about Russia's economy, states that the question is “meaningless”.

|

|

|

The growth in the Russian economy was in part due to the worldwide boom of the 1890s. By 1900, however, there was a slump in international trade. Rapid industrial growth meant that the towns rapidly increased in size and there was overcrowding. With the slump came unemployment; however, there was recovery during 1908 to 1914, during which time state revenues doubled from 2 to 4bn roubles and the number of industrial workers increased from 2.5 to 2.9 million. However, real wages fell during this period. Between 1908 and 1914 there was 40% inflation, but wages only rose 8%. There was enormous industrial unrest. The number of strikes rose from 892 in 1908 to 3,574 in 1914. (There was a dramatic increase from 466 in 1911 to 2,032 in 1912). (The peak was in 1905 at 13,995.)

|

|

|

There was a successful strike in St. Petersburg in 1896-7 by 30,000 cotton spinners and weavers; the won public sympathy and a law was introduced restricting work to 11.5 hours per day! However, whilst this figure is high it must be remembered that there were many public holidays in Russia and only 270 were worked.

|

|

|

All associations of workers striving for better pay and conditions were illegal until 1906.

|

|

|

There were increases in state supervision of work-places; in 1885 22% of workers in industry were subject to the factory inspectorate; this figure rose to 31% by 1909. More and more women were being employed in industry, and this upset trade-union activists who sought to maintain wage-differentials and exclude married women from working altogether.

|

|

Communications and Finance |

|

To contemporaries the existence of a railway was a symbol of progress and modernity. This period saw an extensive expansion of the Russian railway network. Moscow became a meeting point for railway lines. Lines were built from St. Petersburg to Archangel and also, by 1916, to Murmansk. The railways were linked to military planning, which was also important in the development of the trans-Siberian railway, which started in 1892, and was almost completed by 1904.

|

|

|

Total track length increased from 1,000 miles in 1860, to 33,000 miles by 1900 to 45,000 miles by 1917. Railway construction accounted for 1/4 of total net investment during the 1890s. Most of the track was owned by the state — 2/3rds in 1914, and the government also had large share holdings in private ventures. The railways were most important for the transport of freight rather than passengers.

|

|

|

Regarding trade, the government initially supported free trade policies — in liberal tariffs of 1857 and 1868 for instance. However, protectionists argued for higher levels of duty, and the government, seeking sources of revenue, introduced a customs duty from 1877, which it thereafter increased several times. This caused friction with Germany, but the government introduced a differential system which benefited Germany, which in 1913 was the source of 53% of Russian imports and claimed 32% of its exports. There was no economic reason for war between the two empires in 1914.

|

|

|

Industrialisation was opposed by traditionalists, who were also concerned at the increasing level of foreign indebtedness. By 1914 it reached 8 milliard roubles and 1/5th of tax revenue was spent on servicing it. Witte was of the opinion that the rewards were worth the risks, and it was his finance ministry that introduced the gold standard in 1897, which could only be pushed through on the strength of the tsar's personal authority. The gold standard was successful in the sense that it did attract foreign capital, mainly from French investors. Foreign investment increased from 10 million roubles in 1860 to 100 million by 1880 to 700-900 million by 1900 to 1,750 million by 1914. 50% or more went into mining and metallurgy, the remained into textiles, utilities and banking.

|

|

|

Banking also increased and diversified. Initially, the State Bank had an effective monopoly but by 1900 there were over forty commercial banks with deposits of 150 million roubles. This figure rose to 800 million roubles by 1914.

|

|

Education |

|

There was an increase in literacy during this period. The 1897 census showed, for example, that 66.8% of male metalworkers and 33.5% of miners could read. However, for peasants the rate not so high, and in the empire as a whole only approximately 20% of people could read. However, this proportion rose to 44% by 1914. The number of pupils in elementary schools doubled from 4 to 8 million between 1900 and 1916. An education act was passed by the Duma in 1911 that would have made primary education universal, but this was rejected by the upper house. The attitudes of peasants to education also changed, and by the early 1900s younger men were particularly open to the need to acquire rudimentary knowledge. They developed a healthy regard for teachers and local intellectuals.

|

|