|

Britain during the Great War: 1915—16 |

The formation of the coalition government: Asquith and Lloyd George

|

|

|

Asquith announced the formation of the coalition government on 26th May 1915. It claimed to demonstrate national unity, but this was an illusion. For example, Liberals and Unionists were still divided on the issue of free-trade — Liberal in favour, Unionists against. Asquith failed to provide leadership. The efforts of ministers were not coordinated, and ministers ran each ministry independently.

|

|

|

However, Lloyd George did provide great leadership at the ministry of munitions. He transformed the British economy, and managing the ministry in autocratic style, he succeeded in coordinating production that exceeded the demands of the war office. One example of his foresight is supplied by his attitude to machine guns and the Stokes light mortar. At the outset of the war, the army had only 1,330 machine guns; Lloyd George organised the manufacture of 240,506 during it. The war office rejected the Stokes light mortar; Lloyd George negotiated with an Indian maharajah, who financed its manufacture. Tanks were also manufactured as a result of initiatives of Lloyd George, despite the fact that Kitchener described the tank as "a pretty mechanical toy".

|

|

|

A clause in the Army Act provided the government with the power to requisition. Lloyd George controlled the steel industry using this power of requisitioning its raw material. Manufactures gladly accepted a system of 'costing' that provided for costs plus 'reasonable' profits. However, since costs were at the level of the least efficient firm, this meant that many firms made excess profits. Lloyd George later reaped the political benefit, since these same profiteers provided cash for his subsequent “political fund”.

|

|

|

The control of labour was not coordinated, and a mishmash of arrangements persisted. Thus, the local government board was in charge of the Poor Law; the home office controlled the factory acts; labour exchanges were controlled by the board of trade; National Insurance was administered by various independent commissions. A serious shortage of labour ensued in key industries as a result of voluntary enlisting in the services For example, by June 1915 20% of engineering workers had enlisted. It was the ministry of munitions that resisted further recruitment.

|

|

|

Increased profits for industrialists caused resentment among the workers. Workers resented making sacrifices in terms of overtime or their traditional rights, when this brought increased profits to employers. The most militant centres were South Wales and Clydeside, where, in fact, voluntary enlistment in the services was also highest. The government was ineffectual in controlling the employers. Following an act in July 1915, the government had, in theory, the power to punish strikes or resistance to dilution by law, but Lloyd George did not use this weapon. For example, there was a strike in July 1915 by the miners of South Wales in defence of the closed shop. Whilst Runciman wanted to use the law against the strikers, Lloyd George settled the matter behind his back by giving the miners what they wanted. In this way, he was able to secure the provision of munitions throughout the war without any recourse to direct compulsion. There was a significant reduction in the number of days lost due to strikes — working days lost was at 1/4 of the pre-war level. This was probably mainly due to patriotism, but Lloyd George also was a positive influence.

|

|

The Dardanelles campaign and the emphasis on the Western Front

|

|

The Dardanelles committee reviewed the campaign in Gallipolli during June 1915. Kitchener refused to send more than 5 raw divisions to reinforce Hamilton, and also refused to make any experienced generals available. However, on 6th August Hamilton achieved a surprise landing at Sulva bay. Instead of exploiting the advantage the troops were allowed to bathe on the beach, and the Turks had time to send reinforcements. Once again, the British were forced to cling to the barren coast.

|

|

|

The Cabinet did not intend to start any initiative on the Western front until after the reinforcement of the British army was complete. However, Kitchener made an agreement with the French commander-in-chief, Joffre, to support the French assault, and he did so without consulting or informing the Cabinet. In accordance with French instructions, British troops attacked the Germans at Loos during 25th September to 13th October, 1915. Although the German line was breached, the British were unable to exploit the advantage. British casualties were 50,000 to German 20,000. As a result of the failure, Kitchener plotted with General Haig to have French removed as commander-in-chief of the British forces in France. Haig was intimate with George V and his wife. Meanwhile, Kitchener did not know what to do about the Dardanelles. Hamilton was replaced by Monroe, and Monroe recommended immediate evacuation. The Dardanelles committee could not agree on a course of action. Kitchener was sent to rewrite Monro's report. However, Kitchener was still a popular figure with the public, and when The Globe reported that he was about to resign, there was a public outcry, the result of which was it became impossible to sack him. Kitchener refused to remain in the Near East. During his absence the Dardanelles committee was disbanded, and a war committee with fewer members replaced it. Sir John French was replaced by Douglas Haig, and Sir William Robertson became chief of the imperial general staff. Kitchener's role was vastly reduced to, as he put it, "feeding and clothing of the army." He wanted to resign, but was persuaded to stay by Robertson. Haig was a more stable character than Sir John French: resolute in command, loyal to subordinates, and unruffled by defeat. Robertson effectively became supreme commander of all British armies, and he used his power to prevent civilian ministers from having any say in the conduct of the war. He resolutely believed that the Germans could only lose the war by being defeated in France. Consequently, he ordered the immediate evacuation from Gallipoli, and by 8th January 1916 all British forces had been removed from the Dardanelles penisular without further loss.

|

|

|

The British expected the Turks to attack Egypt and garrisoned it with an army of 1/4 million. The attack never came, and in fact the Arabs were encouraged to revolt against the Turks, with Oxford archaeologist, T.E. Lawrence, becoming their "legendary" leader. By the end of 1917 the British had captured Jerusalem. In Mesopotamia the Indian government conducted a campaign to protect the Persian oil wells. In April 1916 the British advanced precipitately towards Baghdad, and were cut off and 10,000 men surrendered at Kut. Further forces were committed — eventually 300,000 in all.

|

|

|

The French stationed a large army at Salonika with the view to relieving Serbia, which had been overrun. But the army remained stationary for most of the war, pinned down by the Bulgarian army — thus 600,000 men, including 200,000 British troops, were effectively interned at Salonika.

|

|

Introduction of Conscription

|

|

|

The Daily Mail represented public opinion, and its sole concern was victory. The war itself was remote for most people. However, the public grew restless and demanded some kind of action — and there was a popular desire to see the introduction of compulsory military service as a result of this. This did not relate to the real needs of the war effort, since the army could not equip all the volunteers it had. Nonetheless, the issue of compulsory military service became the subject of heated debate during autumn 1915, when some Unionist ministers threatened resignation. To defuse the situation Asquith proposed a compromise. Lord Derby was invited to introduce a policy as a result of which men who were of military age could "attest" their willingness to serve. But this device in fact promoted the eventual introduction of compulsory military service. Asquith made the promise that attested married men would only be taken once all unmarried men had been taken. Since this did not distinguish between attested unmarried men and unattested unmarried men, it meant that all unmarried men would have to be conscripted. Thus, in January 1916 the first Military Service Act was passed and all unmarried men between the ages of 18 and 41 were conscripted as a result. There was a degree of protest from Labour — with 30 voting against the bill. Approximately 30 Liberals also voted against it, and Sir John Simon resigned as home secretary. In order to appease the Liberals, it was accepted that conscientious objectors could defend themselves before a local tribunal. No other country at the time had such a procedure, but the provision worked clumsily, and many claims were rejected. Subsequently, the tribunals worked by defining an objector's work as of 'national importance', and so avoided confrontation. However, 45 men were sent against their will to France, which would have meant they could have been executed if they failed to comply with an order. But Asquith had them returned to England. Lloyd George was particularly opposed to conscientious objectors. He said, 'I will make their path as hard as I can.'

|

|

|

Conscription would have placed severe strains on the economic effort of the country, and the Ministry of Munitions responded to it by creating 748,587 new exemption orders. But the demands for compulsory service continued with demands for the conscription of married men. Asquith expected the government to fragment over the issue. However, he was saved by the Easter Rising in Ireland — on 26th April 1916. In the light of this parliament was willing to pass universal military service to the age of 41. Ireland was exempt from military service.

|

|

The Easter Rising

|

|

|

Prior to the Easter Rising: Sir Roger Casement, who was a British consul before the war, went over to the Germans. He tried to recruit an Irish legion from prisoners of war, but this was not successful. A rising was planned for Easter Sunday, 1916. But the Germans implemented no serious plans to support it, and although Casement landed from a German submarine, he attempted to call it off. He was quickly arrested, but the Volunteers decided to carry on with the attempt, and on Easter Monday a group of them took control of the General Post Office, and seven of the rebels proclaimed the Irish Republic. There were five days of fighting, resulting in the deaths of 100 British soldiers and 450 Irish. The Post Office was destroyed as a consequence. Irish public opinion did not support the rising. Those men who had signed the declaration of independence and all but one of the commanders of the Volunteers were shot. As a result the rebels became martyrs, and public opinion in Ireland rapidly changed. Lloyd George took the initiative and proposed a compromise — that there would be immediate Home Rule for the 26 counties of Ireland, and the 6 counties of Ulster would continue to be ruled from Westminster until the conclusion of the war, when there would be an imperial conference to settle the question. However, Redmond rejected the compromise. The result was that the British continued to rule Ireland by force, and the Irish Nationalists effectively seceded from the British parliament.

|

|

|

The upshot was that the Liberal causes of Free Trade, voluntary recruiting and Home Rule had been all abandoned, and the only cause uniting the Liberals was the desire to win the war. Asquith's position became tenuous.

|

|

|

On 5th June the Hampshire with Kitchener on board was sunk. Lloyd George would have also been on the ship, which was travelling to Russia, but for the crisis in Ireland. The Army wished to replace Kitchener by Lord Derby, who would be no more than a figurehead, thus increasing the control of the military — that is, Haig and Robertson — over the conduct of the war. However, the Unionists were opposed to this, and Lloyd George was made secretary for war. But Lloyd George made the mistake of not replacing Robertson at once, the result of which was that Robertson and Haig still had effective control over the direction of the war.

|

|

Submarine warfare and the Battle of Jutland

|

|

|

The biggest threat facing Britain was the shortage of ships to carry goods. Building of merchant ships fell as demand for the navy and munitions. German submarines sunk British ships! In May 1915 the Germans sunk the passenger ship the Lusitania, killing also American citizens. The American president, Woodrow Wilson, strongly protested. The Germans continued with an unrestricted campaign for a further period, but, after more American protests, they imposed restrictions on their submarines, and there were no further sinkings at sight during most of 1916.

|

|

|

The Germans initiated aerial bombardment. Zeppelins were first used to bomb London in April 1915, and aeroplanes were used subsequently. The results were minimal, and British aeroplanes were able to shoot down the German planes quite easily. But the raids caused distress and outcry within Britain.

|

|

|

In Spring 1916 the Germans suspended their campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare. In order to compensate their battle fleet started to venture into the North Sea. The British Grand Fleet under Jellicoe sailed out to meet them. The encounter was at Jutland, and lasted 5 minutes. The Germans turned away, firing a salvo of torpedoes as they did so, which forced the British navy also to retreat. British losses were heavier than the German losses, but the battle left Britain in control of the North Sea. The British lost 3 battle cruisers, 3 armoured cruisers and 8 destroyers. The Germans lost 1 battleship, 1 battle cruiser, 4 light cruisers and 5 destroyers. Thus, five ships were sunk per minute on average. From this point onwards the Germans decided to concentrate on submarine warfare. The drain on British shipping was severe.

|

|

The Battle of the Somme

|

|

The Battle of the Somme, started on 1st July 1916, before Lloyd George's appointment. The engagement typified the weaknesses of the military thinking of the time. The moral of the men was incomparable — it was by far the greatest volunteer force ever to go into battle, but the generals were elderly and lacked imagination. There was still a great belief in cavalry, and large numbers of horses were stationed in France, never to be used. Haig wished to conduct an offensive in the north of France, but he was required to obey Joffre's command, and Joffre insisted that the offensive should take place where the two armies joined, which happened to be on the Somme, where no strategic advantage could be gained. On the first day of fighting there were 19,000 killed, and 57,000 casualties in all — the greatest loss in a single day ever suffered by a British army and the greatest suffered by any army in the First World War. Haig, contrary to his original plan, continued the offensive right through to November. Nothing was gained as a result, and the "zest and idealism" of the men who had volunteered for the war was destroyed.

|

|

|

Lloyd George was angered by the failure of the offensive, and believed Robertson and Haig had misled him. During the same period there was also a failure of a Russian offensive. Rumania joined the Allies, but was rapidly conquered by the Germans.

|

|

The Fall of Asquith — Lloyd George becomes Prime Minister

|

|

|

The war destroyed the Liberal system of free enterprise. It was essential to adopt war socialism in order to sustain the war effort. Runicman predicted that shipping losses would result in a collapse of the British economy by summer 1917. Ministers within the government seriously proposed a negotiated peace, but this was rejected by the Unionists. It was at this point that Lloyd George started to angle for the position of Prime Minister. Lloyd George had to wait for the rebellion to start from outside the government. In due course it did! On 8th November Carson split the Unionist vote over a trivial issue — the disposal of enemy property in Nigeria. However, Law took the hint, and realised that his leadership of the Unionists would not last long unless he was seen to be promoting a more active management of the war. At the same time there was a growing division within the Liberal party, and 49 Liberals were said to support Lloyd George unconditionally, with many others prepared to support him if he was able to form a government. With this support, Lloyd George made a formal proposal to Asquith to establish a war council of just three ministers, with himself in the chair. Law decided to support Lloyd-George, but this angered leading Unionist leaders — Robert Cecil, Austen Chamberlain and Curzon. However, Asquith agreed to Lloyd George's proposal for the war council, only to change his mind under pressure from other Liberal ministers. Then Lloyd George resigned on 5th December, and Asquith also resigned the same day. The king invited Law to form a government, but Law said he would only join a government if Asquith was in it. He, therefore, advised the king to send for Lloyd George. On 7th December Lloyd George met with Labour MPs. He gained support from Law and Addison, who marshalled votes from the backbench liberals. The leading Unionists also joined — Balfour was tempted by the offer of the foreign office; and Cecil, Chamberlain and Curzon joined during the day of 7th December. Curzon made his joining conditional on Churchill being left out of office and Haig remaining Commander-in-Chief. Lloyd George became Prime Minister on the evening of the 7th December 1916.

|

|

War aims and diplomacy

|

|

Britain's allies accused Britain of trying to pick up the spoils of empire. The British tried to allay these suspicions by negotiating a series of partition treaties. On 12th March 1915 they agreed with the Russians that Russia should acquire Constantinople and the Straits. They made an agreement with the French to partition the Turkish empire in Asia, as a result of which Britain would acquire Palestine and Mesopotamia. The Treaty of London (26th April, 1915) with Italy secured Italy's entry into the war in return for a promise that Italy would acquire Tyrol, Istria, and north Dalmatia, but without Fiume.

|

|

|

However, British public opinion was firmly convinced that Britain had gone to war in order to secure the liberation of Belgium. If the Germans had made the offer to withdraw from Belgium, the British would have found it difficult to remain in the war. However, the Germans never made this offer. The only way to achieve the liberation of Belgium was said to be through total defeat of Germany, and hence defeat of Germany was the sole war aim. The British people also supported the idea of the establishment of an organisation that would make future wars impossible. They believed that they were fighting 'a war to end war'.

|

|

|

There was opposition within Britain to the war: the Union of Democratic Control was set up by opponents of the war in September 1914. Ramsay MacDonald was the main politician of the group; E.D. Morel was secretary. The Union demanded (1) an end to the war by negotiation; (2) open diplomacy after the war. Morel was imprisoned for sending printed matter to a neutral country. Bertrand Russell was fined on trumped-up charges for allegedly publishing a pamphlet that discouraged recruiting, and he was also deprived of his lectureship at Trinity College, Cambridge.

|

|

Women and Industry

|

|

The First World War was the first mass war, and shortages of munitions were inevitable. However, at the time people looked for other explanations, and blamed the shortages on slackness. Workers were accused of heavy drinking, and as a result restrictions on drinking were enforced. The strength of beer was reduced and a prohibition on the sale of alcohol during the afternoons was introduced. As a result, the consumption of beer was halved by 1918. But absenteeism was reduced by improvements in working conditions more than anything else. Factory canteens were introduced as a war expense; the ministry of munitions sponsored 887 canteens. Yet the crucial problem was the shortage of labour. This was solved by the introduction of women into the workforce. In July 1915 Christabel Pankhurst staged a demonstration — in fact, her last — in which 30,000 women demonstrated in Whitehall demanding the 'right to serve'. The government acceded, and 200,000 women were employed in government departments; 800,000 were recruited into engineering by 1916; there was a decline in female domestic servants — by 400,000. After the war, there was a return in engineering to male predominance, but nonetheless, women had become more independent.

|

|

The Funding of the War and Inflation

|

|

With the formation of the coalition government, McKenna became Chancellor of the Exchequer. His September 1915 budget was an effective war budget. He increased direct taxation by raising income tax to 3s 6d in the pound and lowering the exemption limit. He also did something to curb the protests against war profits by imposing an excess-profits duty of 50%. This brought in 25% of total tax revenue during the war. He imposed duties on luxury goods such as cars, clocks and watches. Free traders were offended! In 1916 income tax was further increased to 5s in the pound and in 1918 to 6s. These increases did not raise sufficient revenue to pay for the war. However, McKenna made a distinction between normal peacetime expenditure and war expenditure, and accepted that there need be no limit to wartime expenditure provided revenue was sufficient to meet interest payments on the National Debt. The National Debt thus rose from £625 m in 1914 to £7,809 m in 1918. The war was paid for whilst it was waged — but by raising loans from the wealthier classes, who were induced by the attractive rate of 5%. The promise to repay loans meant that the sacrifices of the wealthier classes would be only temporary. With supply of consumer goods reduced by the war effort, there was a shortage of supply, and a consequent increase in prices. As real wages lagged behind the price increases, it was the poor who paid for the war in the form of higher prices. Thus, the funding of the war was inflationary.

|

|

|

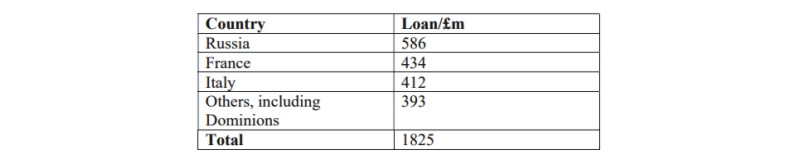

There were other causes of inflation during the period: import prices also rose. However, there was no balance of payments crisis. Export prices also rose, and whilst export volumes fell, their value was sufficient to meet the cost of imports. There was a difficulty in terms of trade with the United States, since there was a shortage of dollars. Loans on the American capital market partly met this shortfall. However, Britain made large loans to her allies during the war:

|

|

|

|

|

British loans to allies during the Great War

|

|

|

It was widely believed that the loans would be repaid at the end of the war.

|

|