|

Knowledge, Belief and Justification |

I. The distinction between knowledge and belief |

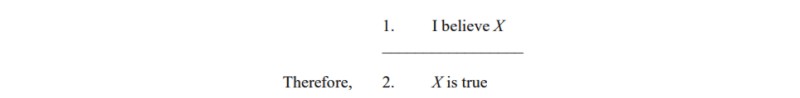

“I believe it, therefore it is true.”

Find counterexamples to this argument. Define what a valid argument is. Explain why this argument is not valid. |

|

|

|

Questions of this kind point us to the way in which we do distinguish naturally between believing something and knowing something. It very often happens that something that we thought or believed was true, turns out to be false. For example, someone might be having a pleasant meal in a restaurant confident that his car is safely in the car-park where he left it, when in fact it has been stolen. Suppose we were having dinner with him, and we challenged his confident assumption that his car is safely parked in the garage, and said, “But do you really know that you car has not been stolen?” In reply, we would expect most people to acknowledge that the security of the car is not certain, and this seems to open up a distinction between knowledge and belief.

|

|

|

Logically, any argument starts with one or more statements that are assumed or asserted to be true. These statements are called premises. From these premises, a conclusion is drawn.

|

|

|

Any argument is valid if the premises force the conclusion to be true. That is, if the premises are true, then the conclusion could not possibly be false. When this is the case we say that the premises entail the conclusion, or that the conclusion is deduced from the premises.

|

|

|

In this case we are examining an argument whose premise is:

|

|

|

1. I believe X.

|

|

|

Here X stands for a statement (or proposition). For example, “I believe that my car is safely parked in the garage”. There is only one premise in this argument, and the conclusion is

|

|

|

2. X is true.

|

|

|

Here X stands for the same statement (or proposition) mentioned in premise; in our example, “It is true that my car is safely parked in the garage.” The whole argument is an example of a logical inference from a single premise to a single conclusion

|

|

|

|

|

We use the line to represent the process of drawing an inference from one or more premises. We also use the word “therefore” (or “thus”, “hence”, “so”, and other terms) to show this process of drawing the conclusion, so strictly speaking we either don't need the line in the above example, or we don't need the “therefore”; however, this is an introduction to the whole idea of valid argument, so we include both.

|

|

|

An argument is said to be “unsound” or “invalid” if the premises do not force the conclusion. What this means is as follows:

|

|

| It is possible for the premise(s) to be true and the conclusion to be false?

|

|

|

Another way of putting this is that the premise(s) and the negation of the conclusion are consistent. In our example what this means is that it is possible that both

|

|

I believe that my car is safely parked in the garage.

and

The car is not in the garage.

are true at the same time. |

|

|

|

We also have another way of putting this: there exists a possible world in which both statements are true. When an argument is unsound we also say that it is a fallacy.

|

|

|

The main way to expose an argument as a fallacy is to offer a counterexample — that is, to show that it is possible for both the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false. This is what we have done so far.

|

|

|

So we have not only illustrated that there is some kind of distinction between believing and knowing, but we have also explained what a valid argument is, and how to demonstrate that an argument is a fallacy.

|

|

|

However, another point has to be made. The use of the symbol X in our statement of the argument indicates that the argument is not really about cars or any other statement about the world. It is an argument about the meaning of the term “I believe”. Hence the whole discussion is really an example of what we call philosophical analysis — that branch of philosophy that deals with meanings, and analyses what words and terms mean.

|

|

|

When we say we believe something, do we mean the same thing as saying that we know something? So far we seem to have drawn a distinction between the two.

|

|

|

However, before we explore this further, let us consider another point about belief.

|

|

II. Belief and doubt |

“I believe it, but I don't think it's true.”

What is odd about this statement? |

|

|

|

This is odd, because when we say we believe something we don't consider that what we believe is false. However, the expression

|

|

| “I believe it, but I am not sure that it is true,” |

|

|

|

is a possible statement. On the other hand, the statement,

|

|

| “I know it, but I am not sure that it is true” |

|

|

|

again seems odd. There are a number of preliminary conclusions that one can draw from this simple example of philosophical analysis.

|

|

|

Firstly, believing and knowing in the sense we are using the terms are terms that express an attitude of a conscious subject (the person who believes or knows) and a proposition (or statement) — what that person believes or claims to know. We make this clear by saying that we are consider what believing-that and knowing-that mean.

|

|

|

This point needs to be made clear because there are contexts in which we use the words believe and know in a different way. Especially, know — we say, for example, “I know how to drive”. This expresses mastery of a skill, and not the conscious grasp of an idea. One could know how to do something without being able to speak; for example, cats know how to eat, but they do not know what their cat food is made of.

|

|

|

We are here dealing with knowing that and not knowing how.

|

|

|

The second point is that, once again, knowing that seems to imply a stronger condition than believing that. It makes sense to say that one can be not sure about something one nonetheless believes, but does not appear to make sense to say that one is uncertain about something one knows.

|

|

|

However, it should be made very clear at the outset that this conclusion is not accepted by every philosopher, and, indeed, we shall later find some very good reasons for rejecting the claimed distinction between believing and knowing.

|

|

|

If the statement

|

|

| “I believe it, but I am not sure that it is true,” |

|

|

|

is an acceptable statement in English (or any language), then it seems to suggest that believing and doubting are not incompatible states of mind. For example, suppose I am in a restaurant and I consider the location of my car. I say to myself, “I believe that my car is in the garage,” but, of course, it is a very real possibility that someone has stolen my car, and this is a practical possibility that we consider on a daily basis — it is so practical that we take out insurance against its occurrence. This again seems to suggest that believing occupies some middle ground between mere opinion, or speculation on the one hand, and knowledge and certainty on the other.

|

|

|

This brings us on to a third point which concerns the relationship between knowing something and certainty. Does it make sense to say that someone really knows something that turns out to be false? We consider this next.

|

|

III. Knowledge and certainty — the tripartite definition of knowledge |

“I know it, therefore it must be true.”

Is this a way that people generally use “know”? Is it possible to define a sense of know that makes this statement true? If we do define it this way, would it be possible to say that we know anything? |

|

|

|

It seems probable that the ordinary language user does not distinguish sharply between contexts in which he or she would use know and contexts in which he or she would use believe. On the other hand, it is also likely that, in common language, the term know implies a stronger condition that believe, and this has appeared to be the conclusion of our philosophical analysis so far.

|

|

|

Yet, even if knowing is a stronger condition than believing does it follow that knowing implies certainty? Clearly, in common language people do use the term know when they are not certain. Certainty implies a state of mind where what you know for certain is so secure that it could not possibly be false.

|

|

|

However, suppose it is true that in common language (that is, unphilosophical language) people do not use know to imply being certain; nonetheless, would it not be possible for a philosopher to define a philosophical use of knowing and state that when he knows something then he could not possibly be wrong?

|

|

|

This leads us to the conclusion that there is a philosophical sense of to know in which knowledge is true, justified belief.

|

|

|

To explain this: firstly, in this sense anything that one knows one also believes. Secondly, however, since what is known is certain, when you know something you not only know that that thing is true, but you are also in possession of some means of demonstrating that it is true. Hence, if you know something you are in possession of a justification of that knowledge. The justification is a process that guarantees that what you know is true — it proves it. Thus, thirdly, since the process of justification guarantees the truth of what it is one knows, then what one knows must be true. It would not be possible to know something that was false.

|

|

|

This has become known as the tripartite definition of knowledge, though it is, of course a theory about what it means to know something, and invites us to consider that there is a special state of mind called knowing to which a philosopher can attain when he is in a position to justify his beliefs.

|

|

|

The tripartite definition of knowledge states that there are three components to knowledge — these are (1) truth; (2) belief; and (3) justification. However, strictly speaking the first component here is redundant; since the process of justification guarantees the truth of what is believed, it is really only necessary to say that knowledge is justified belief.

|

|

|

There is no classical philosopher who has asserted this tripartite definition of knowledge as such, but it is a conception of knowledge that has grown over the ages and has been handed down from one generation of philosophers to the next. However, it is very much open to dispute, as we shall see later.

|

|

|

The tripartite definition of knowledge has its origin in the work of Plato. Plato begins his dialogue The Theaetetus with the question (which he places into the mouth of Socrates) [Plato's works are written mainly in the form of dialogues. He explores philosophical arguments by reporting conversations between his own teacher, Socrates, and people that Socrates met during his life. Of course, some of these dialogues report faithfully what Socrates thought, but others express the ideas of Plato, and these were not the same. Socrates seems to have been mainly a sceptical philosopher, concerned to expose the limitations of our understanding; Plato was a dogmatic philosopher who asserted a great many things, and strove to demonstrate that the philosophy that all knowledge comes from sense-experience (which is called empiricism) is false.]

|

|

| SOCRATES: Talking to the young man, Theaetetus: ... that is precisely what I am puzzled about: I cannot make out to my own satisfaction what knowledge is? Can we answer that question? [This is not quite the opening sentence of The Theaetetus, which is one of the harder of Plato's dialogues. It occurs at paragraph 146.A.] |

|

|

|

The tripartite definition seems to be more clearly expressed in other places; for example, we can see it at work in this following extract from Plato's The Republic. In this dialogue Socrates is discussing the nature of justice with Glaucon.

|

|

SOCRATES: To Glaucon. Then knowledge is set over that which is, and ignorance of necessity over that which is not; and over this that is between, must we not now seek for something between ignorance and knowledge, if there is such a thing?

GLAUCON: Certainly.

SOCRATES: But do we say that belief is anything?

GLAUCON: Surely

SOCRATES: A power distinct from knowledge, or identical with it?

GLAUCON: Distinct

SOCRATES: Then belief is set over one thing and knowledge over another, each according to its own power?

GLAUCON: Yes.

[The Republic, section 477.] |

|

|

|

In other contexts, Plato states the knowledge is infallible because it has special objects — what he calls Forms. This raises another difficulty, since Plato does not accept here that knowledge and belief have the same object. We have assumed that they do (that is a statement or proposition). [A statement is not necessarily the same as a proposition. A statement could be a sentence, whereas a proposition is the idea (or meaning) of the sentence.] However, as we wish to introduce the philosophical analysis of knowledge and belief we leave examination of this problem to another place. However, this is not an issue that we will pursue here. It is sufficient to note for the present what the tripartite definition of knowledge is, and to remark that it has its historical antecedents in the work of Plato. It was also assumed by Descartes, though not explicitly stated by him either, as we shall also see.

|

|

IV. The Possibility of Scepticism |

| If knowledge = true, justified belief, then what processes could justify a belief? |

|

|

If knowledge is true, justified belief, and if the process of justification is one that guarantees certainty, then surely nothing is certain, and nothing is known? One can play a game — take any belief whatsoever and demonstrate that it is not certain.

|

|

|

|

Here is a list of categories of belief

|

|

Religious/theological

Example: I believe that God exists.

Beliefs about material reality

Example: I believe that a table continues to exist even when I am not looking at it.

Scientific beliefs

Example: I believe that gravity causes lead balls to fall to the ground.

Metaphysical beliefs about the nature of the mind.

Example: I believe I have a soul.

Beliefs about the content of the mind.

Example: I believe I am feeling pain.

Beliefs about other minds

Example: I believe that my wife is conscious.

Moral beliefs

Example: I believe that it is wrong to lie.

Political beliefs

Example: I believe in a market economy.

Aesthetic beliefs

Example: I believe that this statue of Venus is beautiful.

Beliefs about the abstract

Example: I believe that there exists an abstract reality that makes my ideas meaningful.

Cosmological beliefs

Example: I believe that the universe began 15 billion years ago with a big bang.

Historical beliefs

Example: I believe that Christopher Columbus discovered America.

Beliefs about the future

Example: I believe that I will die.

Beliefs about mathematics

Example: I believe that 2 and 2 is equal to 4.

Beliefs about logic

Example: I believe that something cannot be both black and not black at the same time.

Beliefs about meaning — analytical beliefs

Example: I believe that knowledge is true, justified belief.

Beliefs about intentions and motives

Example: I believe that President Nixon intended to cover-up the Watergate burglary.

Beliefs about sense-data

Example: I believe that I am seeing a yellow blob right now.

|

|

|

|

There may be other categories that are not included in the list. It is perhaps surprising to discover that there are arguments against the claim that any of these categories can supply beliefs capable of certainty. A global sceptic would argue that there is no category of belief that can attain to certainty.

|

|

|

Sometimes philosophers propose arguments of a global kind that are intended to persuade us that nothing is certain. Here is one famous example.

|

|

From Descartes First Meditation

However, I must note that I am only human, and consequently that I habitually sleep, and that in my dreams I have images of those same things, or even of more improbable things, that insane people see when they are awake. How many times have I dreamt during the night that I was in this room by the fire, whereas in fact I was asleep, naked in my bed? It seems certain just now that I am not looking at this paper with closed eyes; that as I shake my head I am not asleep; that when I deliberately and intentionally hold out my hand, I am aware of it. The images presented in dreams are not so clear and distinct as these are. Yet, on reflecting more carefully about all of this, I remember that I have often been deceived in my sleep by similar illusions, and thinking even more closely, I conclude that there is nothing that conclusively and clearly distinguishes between waking and sleeping. I am quite amazed at this, and I feel so astonished that I am almost convinced that I am actually asleep right now! |

|

|

|

Arguments of this kind also bring to light a distinction between ordinary doubt and philosophical doubt. In the ordinary course of daily events people rarely consider the possibility that what they take to be real is not real. For example, most people would not consider whether their house has popped out of existence when they have left it, or that they are in fact dreaming, and not really awake. Ordinary doubt is taken up with questions of another kind — for example, a worried parent might not be sure that his child has gone to school, a scientist might doubt the validity of another experimenter's observations.

|

|

|

Sometimes philosophers, like Descartes, do raise questions about the things that in the ordinary course of events we might take for granted — hence the distinction between ordinary and philosophical doubt. However, for every philosopher that proposes a philosophical doubt there is another who tries to refute it. Not everyone agrees that doubt is the best starting point for philosophical enquiry. In Western philosophy it has historically occupied a central position, especially since Descartes reaffirmed the possibility of global scepticism and also offered his own unique solution to it.

|

|

V. The Argument from Authority |

“Aristotle said X, therefore X is true.”

How valid is this argument? |

|

|

|

This argument is known as the argument from authority, and it is generally agreed among philosophers that it is not valid. The mention of Aristotle here might make this seem obvious; but there was a time in the history of ideas when practically everything that Aristotle wrote was taken as true, and it was dangerous to say that it wasn't.

|

|

|

However, it is surprising to discover that most of what one believes is also based on some authority or other — for example, what we study in schools is what is written in textbooks. We hardly ever reconsider anything afresh. It is part of the environment of Western philosophy, at least as handed down from Descartes, that each philosopher should reconsider everything afresh and from first principles. Yet this too is disputed.

|

|

VI. The Quest for a Foundation to Knowledge —Self-evident truths and Empiricism |

Can there be an argument that makes no assumptions whatsoever?

“Every argument makes some assumption, even if it is only the assumption that the logic of the argument is sound; hence there cannot be any knowledge.” Is this true? |

|

|

|

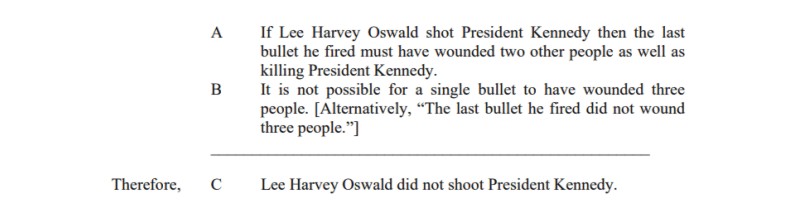

We have seen that logical inference builds from premises to conclusions. Here is an example of a valid deduction

|

|

|

|

|

[This argument is taken from Oliver Stone's film, JFK.]

|

|

|

This argument (although it might appear controversial) is in fact valid, in the sense that if the premises are true, then the conclusion could not possibly be false. The controversy raised by this argument is contained in the premises. Anyone who wishes to maintain that Lee Harvey Oswald did shoot President Kennedy must deny the truth of one or both of the two premises.

|

|

|

In this argument statement C is justified by means of an inference from statements A and B.

|

|

|

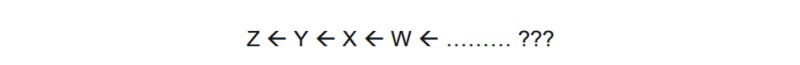

We are interested here in the nature of justification. Justification in this sense creates a chain of deductive inferences. Statements are justified by showing that they follow logically from other statements. But this creates a problem of what we call an infinite regress. Suppose statement Z is justified by inference from statement Y, and statement Y is justified by inference from statement X, and so forth. At what point will the process of justifying one statement by deriving it from another stop?

|

|

Z is justified by Y

Y is justified by X

X is justified by W

and so on, ad infinitum. |

|

|

|

Diagrammatically we might represent this situation by

|

|

The arrows point in the direction of logical inference; but the justification goes the other way — Z is true because it follows logically from Y, and so on.

The arrows point in the direction of logical inference; but the justification goes the other way — Z is true because it follows logically from Y, and so on.

|

|

|

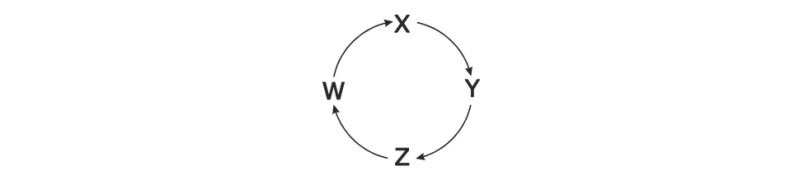

One way we might get around this problem is to propose an alternative structure. Such as justification in a circle.

|

|

|

|

|

Of course this does not seem any better. As we are going around in a circle every statement is justified by appeal to every other — but what if the whole structure is wrong? On the other hand, this alternative is seriously proposed in what is known as the coherence theory of truth, which we shall also examine later.

|

|

|

If we reject the idea of justifying in a circle (and the coherence theory of truth), then we need to stop the infinite regress in some way. We need to appeal to some kind of proposition that does not require justification by appeal to other propositions. Such a proposition would be a self-evident truth.

|

|

|

A self-evident truth is one that justifies itself.

|

|

|

The most “obvious” candidate for self-evident truths are statements about immediate sense-experience. For example, “I am seeing a blue dot now” is the sort of statement that has been claimed to have the quality of being self-evident. It is self-evident because it is a true description of what is seen. Hence, perception and sense-experience generally are held by many to be the basis of knowledge. The idea is that by starting with self-evident descriptions of sense-experiences we can build on that foundation to establish (and justify) the truth of other statements that may not appear at first to be based on sense-experience.

|

|

|

The belief that there is a self-evident foundation for knowledge can be called the axiomatic method. An axiom in logic or mathematics is a starting proposition from which a theory is developed. In the theory of knowledge whatever is self-evidently true would constitute an axiom of knowledge.

|

|

|

The belief that all knowledge is based solely on sense-experience is known as empiricism.

|

|

VII. The Dialectic Method — and Rationalism |

“I know that I exist.”

Is this certain? |

|

|

|

Empiricism has been subjected to thorough critique ever since Plato, who was vehemently opposed to it, and the debate between empiricism and its alternative, rationalism, lies at the heart of Western philosophy. It is central to the dialectic method by means of which Western philosophy “progresses”.

|

|

|

Western philosophers do not agree about fundamentals. There is no single common set of beliefs or dogmas that all Western philosophers accept as truths. Western philosophers agree to disagree, even about fundamentals. They also agree to enter into debate with each other, and to propose arguments and counter-arguments. One argument is proposed as a thesis, and objections to this argument are made, and an antithesis is offered in its place.

|

|

|

Although this might appear to indicate that Western philosophy does not develop, that is not really the case. The sincerity of all philosophers to discover the truth, no matter how painful that may be to them personally, requires them to acknowledge the force of certain counter-arguments to their dearly cherished beliefs. In acknowledging these counter-arguments they are forced to refine their own arguments, and improve on them; alternatively, they must give up their thesis and acknowledge “defeat”. So Western philosophy proceeds through the exchange of argument and counter-argument; through the battle between thesis and antithesis. This is why dialogue is one of the main forms of Western philosophical literature; debate lies at the heart of the method. The method is known as the dialectic method, and its invention is attributed to Plato.

|

|

|

Returning to our current enquiry, if empiricism is the thesis then rationalism is the anti-thesis.

|

|

|

In its most general form, rationalism denies empiricism. It maintains (1) that there is knowledge and (2) that knowledge is not obtained from sense-experience alone.

|

|

|

Rationalism encompasses a very wide range of beliefs — one of the most extreme forms of rationalism was proposed by Descartes. He first attempted to demonstrate that sense-experience could not be the basis of knowledge. The following passage indicates what he held to be the foundation of knowledge.

|

|

Descartes: Discourse on the Method

I decided to reject as false all the reasons that I had previously accepted has having been demonstrated to be truth. I did this firstly because our senses sometimes deceive us, so it is possible that nothing is exactly what we imagine it to be, and secondly because some men deceive themselves by making errors in their reasonings, committing paralogisms even in the simplest cases of geometric proof, and I realized that I was as much prone to make errors as anyone else. Likewise, since any thought or idea that we can have while awake can occur to us in our sleep, I resolved to take everything that ever entered into my mind as containing no more truth than the illusions of my dreams. Nonetheless, immediately after forming this idea I observed that even when I thought that everything was false, it was nonetheless essential that the “I” who is the subject of this thought is something, and so I concluded that I think, therefore I am was absolutely certain and incapable of being overturned as a truth by even the most extravagant skeptical propositions. I concluded that I could without any doubt whatsoever accept this statement as the first principle of Philosophy that I had been looking for. |

|

|

|

Descartes takes the statement I think, therefore, I am as a self-evident truth. Elsewhere, for example, in the Meditations, he expresses this idea by saying, “I am, I exist is a necessary truth”.

|

|

|

The Latin expression for I think, therefore, I am is Cogito, ergo sum. Hence, this argument is known as The Cogito.

|

|

|

To summarise the point we have reached so far. Empiricists propose that there are self-evident truths based on sense-experience (sense-perception); Descartes, as an example of a rationalist, proposes that his own existence forms the basis of what is self-evidently true.

|

|

|

Let us suppose for the moment (and only for the sake of developing the argument) [this exploration of ideas on a what if and just suppose it is true basis is another hallmark of the technique of Western philosophy. We explore with an open mind the consequences of an idea, always bearing in mind that we can go back and reject the starting point at a later stage if we wish..] that Descartes is right and the cogito is self-evidently true. Then what could make that true? If it is perception that makes sense-experience self-evident, then there must be another form of perception that makes the cogito true. This perception of one's own “soul” and affirmation of one's own existence is not a form of sense-perception. It is, therefore, another form of experience. In other words, the mind must be equipped with another faculty that gives it the power to affirm its own existence.

|

|

|

Descartes called this power reason or rational insight. Another term used by rationalists to denote a power of the mind that is independent of sense-experience is intuition. Here intuition is being used in a specific philosophical sense and should not be confused with “intuition” in the sense of “having a hunch” or “gut feeling” about something. It is used to denote a power of “seeing” into one's own soul and affirming its existence.

|

|

|

The philosopher Bertrand Russell used the term acquaintance for knowledge that can lead to self-evident truths.

|

|

| We shall say that we have acquaintance with anything of which we are directly aware, without the intermediary of any process of inference or any knowledge of truths. [Bertrand Russell: The Problems of Philosophy, Chapter 5: Knowledge by Acquaintance and Knowledge by Description.] |

|

|

|

He goes on to cite sense-data as objects with which we are acquainted; thus, it would appear that he is very much an empiricist, though it later emerges that he is not!

|

|

|

Russell draws an important distinction between knowledge of truths (knowing that) and knowledge of things (acquaintance) which it will be helpful to clarify. To take his own example: in perception a person becomes acquainted with sense data. Then he forms a judgement about the sense-data. For example, he may become acquainted with a brown sense-datum. At present, however, he has no knowledge of truth; then he forms the judgement, this sense-datum is brown. The judgement, which is true and certain, is based upon the acquaintance with the sense-datum. Thus, all self-evident truths (if there are any!) are based on direct acquaintance with some object or other.

|

|

|

Hence, if Descartes is right about the cogito, what makes the judgement cogito, ergo sum self-evidently true is the direct acquaintance of the mind with itself.

|

|

|

As already indicated, Russell appears to affirm empiricism when he says that we have acquaintance with sense-data, and this can provide the basis for truth. On the other hand, he later advances the view that we are also acquainted with objects that are not sense-data, which he calls universals.

|

|

| We speak of whatever is given in sensation, or is of the same nature as things given in sensation, as a particular; by opposition to this, a universal will be anything which may be shared by many particulars, and has those characteristics which ... distinguish justice and whiteness from just acts and white things. [Bertrand Russell: The Problems of Philosophy, Chapter 9: The World of Universals.] |

|

|

|

If universals exist then they do not exist in space and time. They are non-temporal, non-spatial entities. We call such entities abstract entities. Hence, Russell (and most especially Plato before him) maintain that we are directly acquainted with an abstract reality, composed of universals. This is another way of saying that the mind is equipped with a power of direct intuition (acquaintance) that is separate from the five external senses. We will consider universals and whether we are indeed acquainted with them at more length on another occasion. Here we cite universals as a further candidate for objects that may be known by direct acquaintance. Rationalists generally maintain that there are universals, and Plato, the founder of Rationalism, used his arguments in favour of the existence of universals (which he called Forms ) as the basis of his attempt to refute empiricism.

|

|

VIII. Scepticism, Existentialism and Faith |

“Faith is possible because knowledge is not certain.”

Is this a true point? |

|

|

|

Let us now consider the possibility of global scepticism. As the student's knowledge of philosophy increases, he or she will be familiarised with a host of powerful sceptical arguments. For example, there is no agreement among philosophers that there are such things as sense-data — primary constituents of experience that can act as the foundation to knowledge. Empiricists on the other hand deny the existence of universals and claim that general knowledge and meaning is abstracted from sense-experience. Russell proposed the following sceptical argument: how do we know that we were not created five minutes ago complete with all our memories? In the film Blade Runner certain androids have been manufactured complete with inbuilt memory chips that give them the illusion of having had a real past, which they have not had. How do we know that this outlandish possibility is not our own? Scepticism abounds with arguments that challenge our assurance of having knowledge.

|

|

|

Here is a very famous example of such an argument offered by Descartes — it is known as the Evil Genius argument.

|

|

From Descartes First Meditation

Let me imagine, therefore, not that there does not exist a true God, who would act as the sovereign source of truth, but rather an evil demon, who is cunning, deceptive and powerful, and who employs every means he can to lie to me. Let me consider the possibility that all external things, the heavens, the air, the earth, colours, shapes and sounds, are only illusions and deceptions used by this demon to fool me. I shall consider the possibility that I actually have no hands, eyes, flesh, blood or senses, and only believe mistakenly that I have these things. I shall fix firmly on this idea, so as to find out whether it is within my power alone to arrive at the truth, or if not, to at least be able to maintain an impartial judgement. For this reason I want to be very careful not to believe in anything that is false, and in that way, I will prepare myself mentally against any trick that this powerful deceiver can impose upon me, whatever his powers of deception and cunning may be. |

|

|

|

Descartes uses this argument to undermine even our conviction that the truths of Mathematics and Logic are certain.

|

|

|

Thus, global scepticism — doubt of everything whatsoever — is a possible conclusion of all these particular sceptical arguments, and the reader is warned that there will be many more to come in his experience as he delves further into Philosophy.

|

|

|

The modern philosophy of Existentialism is another response to this sceptical predicament. There is an obvious criticism of global scepticism, namely that it is a position that is crippling for life, and incompatible with day to day living. This is a point that Hume makes in his concluding section to his Enquiries.

|

|

| But a Pyrrhonian [= global sceptic] cannot expect, that his philosophy will have any constant influence on the mind: Or if it had, that its influence would be beneficial to society. On the contrary, he must acknowledge, if he will acknowledge any thing, that all human life must perish, were his principles universally and steadily to prevail. All discourse, all action would immediately cease; and men remain in a total lethargy, till the necessities of nature, unsatisfied, put an end to their miserable existence. Hume: An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Section 12: Of the Academical or Sceptical Philosophy.] |

|

|

|

We shall examine Hume's own solution to the sceptical problem later. But an existentialist would agree with this quotation. Global scepticism is something that can exist only in a state of inactivity; as soon as a person steps out into the world, and is forced to act, that person must commit himself to a system of belief. Since there is no objective argument that compels the actor to commit to one system of belief rather than another, that commitment is an act of faith.

|

|

|

In Fear and Trembling the Christian existentialist, Soren Kierkegaard, gives an illustration of this problem drawn from a Biblical story of Abraham and Issac. Abraham was only granted a son, Isaac, at a very advanced age — his wife, Sarah, was well beyond the age of child-bearing. One day he became convinced that he had to sacrifice Isaac to Jehovah on the mountain in Moriah. He went to do so. At the last moment God presented him with a lamb, and he sacrificed that instead.

|

|

|

There is an obvious ethical problem here. Abraham was prepared to sacrifice his son — that is, to murder him. He was prepared to do this because he believed that he was commanded to do so by God.

|

|

| I have no mind to take part in such mindless praise [of Abraham]. If faith cannot make it into a holy deed to murder one's one son, then let the judgement fall on Abraham as on anyone else. If one hasn't the courage to think this thought through, to say that Abraham was a murderer, then surely it is better to acquire that courage than to waste time on underserved speeches in his praise. The ethical expression for what Abraham did is that he was willing to murder Isaac; the religious expression is that he was willing to sacrifce Isaac; but in this contradiction lies the very anguish that can indeed make one sleepless; and yet without that anguish Abraham is not the one he is. [Soren Kierkegaard: Fear and Trembling.] |

|

|

|

If God exists, and if God commanded him to kill his own son, then his actions are the expression of greatest obedience to the will of God; if God does not exist, and Abraham was only deluded in believing that he should kill his own son, then his actions are the expression of a deeply troubled mind. If an angel appeared to Abraham and instructed him to kill his son, then Abraham has the problem of interpreting this sign — what is the angel? If it is a real angel and a messenger from God, then he must kill his son; but it is also possible that the angel is a product of his own diseased mind. There is nothing in the sign (the appearance of the angel) that could determine it one way or another. For Kierkegaard, and Existentialists generally, this is the character of all life. We are forced by the necessity to act to make a commitment to an interpretation of life; but the evidence does not force one to act in any given way. The commitment is an act of faith. Existentialists describe this by saying, you believe it on the strength of the Absurd.

|

|

| ... ignorance is the precursor of the absurd, the irrational and inexplicable fact that an individual lives in the world he does live in. The absurd is that part of man's situation which is intractable to generalizations or system-making. It is the brute fact that he exists as a concrete thing in the world. To accept the absurd is to accept a paradox, and for this one needs faith. [Mary Warnock, Existentialism, Chapter 1, Ethical Origins.] |

Existentialism is one response to the problem raised by scepticism; it is a response to the absurd situation or paradox that we exist in a world where action is obligatory, but where nothing is certain.

|

|

IX. The a priori and the transcendental deduction |

Are mathematical statements, true, justified beliefs?

Does mathematical proof justify a mathematical statement?

“Nothing can be both black and not black.”

Is this true? It is necessarily true? If so, from whence does this logical knowledge derive? |

|

|

|

What both empiricism and rationalism agree upon is the view that there is a foundation to knowledge. In other words, empiricism and rationalism agree that there are self-evident truths based on some form of direct acquaintance with objects. Where they disagree is on what this direct acquaintance is. Empiricists maintain that direct acquaintance is confined only to sense-experience; rationalists maintain that there is either rational insight into the existence of one's own soul (Descartes) or direct acquaintance with an abstract reality (Plato).

|

|

|

It is worth remarking here that what empiricists and rationalists are debating is also the conception of man. The empiricist view is consistent with the belief that man is an information processing “machine”. Empiricism is consistent with the view that man has evolved from other less complicated forms of biological organisation over time. Rationalism requires that man has an extra-sensory power of the mind, that might be called reason, and this is not consistent with the Darwinian theory of evolution.

|

|

|

Questions regarding what we know are questions considered in Philosophy under the heading of Theory of Knowledge, or Epistemology. Questions regarding what we are are considered in Philosophy under the heading of Metaphysics.

|

|

|

There is a very strong connection between these two branches of Philosophy. For example, Plato attempted to demonstrate the existence of the soul by arguing that we have knowledge of an abstract reality that is only consistent with the existence of the soul. This is an argument from the Theory of Knowledge to Metaphysics. He specifically claimed that knowledge of this abstract reality must have been given to each person prior to his birth, and that all knowledge is thus based on recollection of our pre-existence. Since we pre-exist our birth, we must have a non-material soul. Kant gave the name transcendental deduction to any argument that attempts to explain how we can know something that could not be derived from sense-experience. [“The explanation of the manner in which concepts can thus relate a priori to objects I entitle their transcendental deduction; and from it I distinguish empirical deduction, which shows the manner in which a concept is acquired through experience and through reflection upon experience...” Kant, Critique of Pure Reason — The Principles of any Transcendental Deduction. For “experience” in the above passage read “sense-experience” and for “a priori” read “not through sense-experience”. If you also substitute “universals” or “forms” for “concepts” you get the form of Plato's argument.] Plato's argument for the immortality of the soul is a form of transcendental deduction since he attempts to explain our capacity to know of abstract reality by postulating the existence and immortality of the soul.

|

|

|

Rationalism is the attempt to arrive at objective knowledge through an examination of the ideas that are innate in us. For an idea to be innate means that it could not be derived from sense-experience. It must come from some other faculty or power of the mind. Many rationalists believe that innate ideas have in fact been placed in their mind by God. This is the view of Descartes. The first and foremost rationalist is Plato. He believed that the soul is immortal and predates our birth. In other words, we existed in another form before we were born. Prior to birth we go through a process of amnesia and forget our previous existence. However, our capacity to know anything depends on the knowledge we acquired in our former existence. Whenever we learn something we are really only recollecting it. Descartes merely asserts that we have innate ideas and does not discuss the doctrine of recollection. It is sufficient for him that God has placed innate ideas directly into our minds.

|

|

|

In order to demonstrate the existence of innate ideas rationalists must find some branch of knowledge that accepted as being knowledge and also cannot be derived from sense-experience. Knowledge of mathematics and logic are the prime candidates.

|

|

|

Of course, this is a matter of considerable debate, and empiricists do not agree that mathematical and logical principles are innate. Nonetheless, the power of this argument can be seen from the following extract from Russell's The Problems of Philosophy.

|

|

| One of the great historic controversies in philosophy is the controversy between the two schools called respectively 'empiricists' and 'rationalists'. The empiricists — who are best represented by the British philosophers, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume — maintained that all our knowledge is derived from experience; the rationalists — who are represented by the Continental philosophers of the seventeenth century, especially Descartes and Leibniz — maintained that, in addition to what we know by experience, there are certain 'innate ideas' and 'innate principles', which we know independently of experience. It has now become possible to decide with some confidence as to the truth or falsehood of these opposing schools. It must be admitted, for the reasons already stated, that logical principles are known to us, and cnnot be themselves proved by experience, since all proof presupposes them. In this, therefore, which was the most important point of the controversy, the rationalists were in the right. [Bertrand Russell, The Problems of Philosophy, Chapter 7: On our Knowledge of General Principles.] |

|

|

|

Russell's confident statement has not put the “controversy” to an end; the debate continues and at present empiricism is in the ascendancy in our Western culture. Nonetheless, Russell's reaction illustrates the power of the objection that logical knowledge cannot be derived from experience. He states also that mathematical knowledge cannot be derived from experience.

|

|

|

Russell explicitly rejects Plato's conclusion that innate ideas must imply pre-existence. He writes

|

|

| It would certainly be absurd to suppose that there are innate principles in the sense that babies are born with a knowledge of everything which men know and which cannot be deduced from what is experienced. For this reason, the word 'innate' would not now be employed to describe our knowledge of logical principles. The phrase 'a priori' is less objectionable, and is more usual in modern writers. Thus, while admitting that all knowledge is elicited and caused by experience, we shall nevertheless hold that some knowledge is a priori, in the sense that the experience which makes us think of it does not suffice to prove it, but merely so directs our attention that we see its truth without requiring any proof from experience. [Bertrand Russell, The Problems of Philosophy, Chapter 7: On our Knowledge of General Principles.] |

|

|

|

Thus the rationalists' strongest argument would appear to start with the claim that there exists a priori knowledge. This is knowledge that cannot be logically derived from sense-experience, and hence must have a source independently of experience. Rationalists then seek to explain where this knowledge comes from. Descartes says it is directly implanted into our minds by God; Plato says that it derives from our pre-existence; Russell, who is also a rationalist, says that it comes from a direct acquaintance with universals.

|

|

X. The Empiricists' Reply and the Non-Cognitivism of Hume |

“It is 99% certain.”

Is this an acceptable statement? |

|

|

|

The strongest argument the rationalists would appear to have in defence of the existence of innate ideas or the a priori is the existence of logical and mathematical necessary truths.

|

|

|

There are a number of possible empiricists replies. One reply, that mathematical and logical truths are true by definition or convention is offered by A.J. Ayer in Language, Truth and Logic. We will reserve examination of that argument for another occasion.

|

|

|

There is another response offered by empiricists which is advanced by Hume in his Enquiries.

|

|

Hume's reply to The Method of Doubt

There is a species of scepticism, antecedent to all study and philosophy, which is much inculcated by Descartes and other, as a sovereign preservative against error and precipitate judgement. It recommends an universal doubt, not only of all our former opinions and principles, but also of our very faculties; of whose veracity, say they, we must assure ourselves, by a chain of reasoning, deduced from some original principle, which cannot possibly be fallacious or deceitful. But neither is there any such original principle, which as a prerogative above others, that are self-evident and convincing; or if there were, could we advance a step beyond it, but by the use of those very faculties, of which we are supposed to be already diffident. The Cartesian doubt, therefore, were it ever possible to be attained by any human creature (as it plainly is not) would be entirely incurable; and no reasoning could ever bring us to a state of assurance and conviction upon any subject. [David Hume: An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Section XII: Of the Academical or Sceptical Philosophy.] |

|

|

|

In fact, Hume acknowledges the power of the sceptical arguments, but claims that none of these arguments are sufficient to overthrow the natural, instinctive beliefs of human nature.

|

|

| The great subverter of Pyrrhonism or the excessive principles of scepticism, is action, and employment, and the occupations of common life. These [sceptical] principles may flourish and triumph in the schools; where it is, indeed, difficult, if not impossible, to refute them. But as soon as they leave the shade, and by the presence of the real objects, which actuate our passions and sentiments, are put in opposition to the more powerful principles of our nature, they vanish like smoke, and leave the most determined sceptic in the same condition as other mortals. |

|

|

|

Rationalism is effectively based on the assumption that we can draw a particular distinction between knowing and believing — Hume effectively denies this, which brings us back to the very beginning of our discussion. There we seemed to follow a logical chain of reasoning that led us through the examination of the concepts of knowledge, belief and justification to the tripartite definition of knowledge as true, justified belief. However, if we revisit this argument we shall discover, in the light of what has been said subsequently about rationalism, that the claim that knowledge is true, justified belief implies metaphysical assumptions about the nature of the human mind which can also be questioned. Rationalists maintain that the mind has an extra-sensory power, that they call reason, that enables them to know things for certain independently of experience. Therefore, they draw a strong distinction between knowledge and belief. Knowledge, which is founded on reason, has for its objects universals (or forms) that are non-spatial and non-temporal. It is because one can apprehend such universals that necessary truths, such as those of logic and mathematics, can be grasped.

|

|

|

But suppose that no such extra-sensory power of reason exists; then it would not be possible to justify this division between knowledge and belief. To say that we can comprehend by knowledge an idea of absolute certainty that does not permit of any possibility of error is to say that the mind is capable of attaining to a particular state of mind. It is quite possible to argue that no such state of mind exists, and consequently the distinction implied in the tripartite definition of knowledge collapses. If this is so, then the distinction between knowledge and belief must be based on something other than the idea of a process of justification that guarantees certainty; if justification is involved, then it does not guarantee certainty in the sense that what is know could not possibly be false.

|

|

|

The approach that Hume takes in the Enquiries is a psychological one. He hardly ever uses the term know in his writings, but prefers the term belief. This is because for him there is only belief. He is how he distinguishes belief from imagination.

|

|

| I say, then, that belief is nothing but a more vivid, lively, forcible, firm, steady conception of an object, that what the imagination alone is ever able to attain. |

|

|

|

Taking our cue from this extract, we could say that Hume would regard knowledge as an intense form of belief. A belief is accompanied, psychologically, but a measure of conviction that, for Hume, is ultimately based on past experience. We only believe that it is possible that a die will come up with a six, because in the past die throws have only produced sixes on a certain proportion of occasions, but we are convinced that a lead ball will fall when dropped, because lead balls always do fall. Thus, beliefs are accompanied by a level of intensity. Some beliefs are held so intensely, that we say that we know them.

|

|

|

However, what this implies is that something that is known could turn out to be false. There are outlandish possibilities, hardly ever seriously contemplated in ordinary life, that just occasionally turn out to be real. A man jumps from an aeroplane and his parachute does not open. He may be convinced that he will die on impact, but by chance he falls through trees that slow his rate of descent and he survives. Improbable and outlandish, but possible nonetheless.

|

|

|

The whole rationalist (and Cartesian) approach to knowledge assumes that we are capable of attaining to some kind of objectivity that effectively means that we are able to “jump out of our own skins”. If we look at life through out own eyes, it is claimed, we will see that we cannot transcend our own situation and personal history. I can examine my beliefs one at a time, but I cannot examine them all together at the same time, for there is nothing to compare them to. Of course, the rationalist does believe that reason provides an independent faculty of the mind that enables all beliefs to be examined afresh and reconstructed anew; but if you are not a rationalist, then you may be forced to conclude that such a programme cannot be started. There is knowledge, but what we call knowledge is what we have learnt over our lives, and much of which we cannot doubt for the simple reason that there is no independent material to compare them to. In rationalism it is reason that provides this independent source of truth. Some empiricists maintain that sense-data are sufficient; but other empiricists, of whom Hume and Wittgenstein are prime examples, do not.

|

|

|

We can summarise this difference of opinion as follows.

|

|

Descartes

Knowing is a different from believing because there is a process that guarantees truth. The Method of Doubt uncovers what is incapable of doubt.

Hume

Knowing is a stronger form of belief but not essentially different from it. The difference is only a difference of feeling or intensity. The Method of Doubt is an illusion, for it is not possible to consider the possible falsity of all your beliefs at once. |

|

|

XI. Correspondence and Coherence Theories of Truth |

One child might say to another: “I know that the earth is already hundreds of years old” and that would mean: I have learnt it.

How do children learn? |

|

|

|

Truth is a logical operator on sentences. For example, consider what we mean when we say

|

|

|

It is true that this tree is green.

|

|

|

We could write this alternatively as

|

|

|

“This tree is green,” is true.

|

|

|

The statement “It is true that...”, or the operator “... is true” would appear to be redundant (unnecessary). We could replace either sentence by simply

|

|

|

This tree is green.

|

|

|

The operator “... is true” asserts a relationship between the sentence “This tree is green” and the fact in the world that makes the sentence true.

|

|

|

The mere fact that I utter a sentence does not make the sentence true, or force a correspondence between the sentence and the world. For example, I could say “A statue of Elvis Presley has been found on Mars”. This is a perfectly meaningful sentence in English, but happens to be false. When the sentence is false there is no correspondence with fact (the world or reality). Hence, when we use the operator “... is true” we are drawing people's attention particularly to the claim that there is a correspondence between the sentence and reality.

|

|

|

I tell you, it is true that there is a statue of Elvis on Mars!

|

|

|

Of course, this form of language can be abused. It asserts strongly that what is said is no mere figment of the imagination, but naturally people may use this form of language to reinforce a lie or tall story.

|

|

|

The idea that all true statements of our language correspond to facts about the real world that makes them true is called the correspondence theory of truth. As we have seen, some notion of correspondence seems to be built into our notion of what truth is, and when we say that something is true we are searching for facts about the real world that make them true. It is a sceptical problem if we cannot find those facts, or if the facts that make the statement true are remote and not immediately to hand.

|

|

|

Rationalism and empiricism (in the form advanced by A.J. Ayer) rely strongly on the correspondence theory of truth. Descartes, for example, seeks to base all truth on correspondence with innate ideas present to the mind through the faculty of reason. A.J. Ayer seeks to base all truth on correspondence with sense-data, ultimate constituents of sense-experience.

|

|

|

However, we have also seen that there is an alternative form of empiricism that questions correspondence as the ultimate basis of truth. This begins to emerge in the following quotations from Wittgenstein's On Certainty.

|

|

166. The difficulty is to realize the groundlessness of our believing

192. To be sure there is justification; but justification comes to an end.

205. If the true is what is grounded, then the ground is not true, nor yet false. |

|

|

|

In these extracts Wittgenstein denies the axiomatic method. He objects to the idea present in rationalism and in some forms of empiricism that there is a self-evident foundation for knowledge. Truths cannot be justified in that way.

|

|

|

For him truths are acquired through social interaction. As children we are inducted into a way of living.

|

|

140. We do not learn the practice of making empirical judgments by learning rules: we are taught judgments and their connexion with other judgments. A totality of judgments is made plausible to us.

141. When we first begin to believe anything, what we believe is not a single proposition, it is a whole system of propositions. (Light dawns gradually over the whole.) |

|

|

|

We are taught a system of beliefs, and we are also taught how to connect these beliefs together. We are inducted as children into a way of living, and learn the rules whereby our parents and elders live. This makes a “totality of judgements plausible to us”.

|

|

142. It is not single axioms that strike me as obvious, it is a system in which consequence and premises give one another mutual support.

144. The child learns to believe a host of things. i.e. It learns to act according to these beliefs. Bit by bit there forms a system of what is believed, and in that system some things stand unshakably fast and some are more or less liable to shift. What stands fast does so, not because it is intrinsically obvious or convincing; it is rather held fast by what lies around it.

163. Does anyone ever test whether this table remains in existence when no one is paying attention to it?

We check the story of Napoleon, but not whether all the reports about him are based on sense-deception, forgery and the like. For whenever we test anything, we are already presupposing something that is not tested. Now am I to say that the experiment which perhaps I make in order to test the truth of a proposition presupposes the truth of the proposition that the apparatus I believe I see is really there (and the like)?

164. Doesn't testing come to an end?

165. One child might say to another: “I know that the earth is already hundreds of years old” and that would mean: I have learnt it. |

|

|

|

We can summarise Wittgenstein's attack on Descartes' Method of Doubt by the slogan “doubt presupposes certainty.”

|

|

|

Effectively, Wittgenstein is advocating what we call a coherence theory of truth. In its extreme form this coherence theory denies that there is a reality that exists independently of the sum total of judgements we make about it. What is real is what we say is real within the total system of our beliefs. What makes a system of statements true is their total coherence with each other; the system is consistent! However, consistency is also not a quality that lies outside the system. We cannot say that the whole system corresponds to a consistent (or logically possible) world. Consistency is also part of the system. Thus, coherence is all there is.

|

|

|

This is an extreme form of the coherence theory, and seems to deny that there is any kind of correspondence between statements of our language and reality (the world of fact) at all. However, there is an alternative mid-way view.

|

|

XII. Pragmatism and the Quinian model of truth |

|

“But we know that atoms exist.”

|

|

|

Do we? In what sense do atoms exist?

|

|

|

The founder of pragmatism, William James, poses the problem facing a correspondence theory of truth in his essay, Pragmatism's Conception of Truth.

|

|

The popular notion is that a true idea must copy its reality. Like other popular views, in this thesis one follows the analogy of the most usual experience. Our true ideas of sensible things do indeed copy them. Shut your eyes and think of yonder clock on the wall, and you get just such a true picture or copy of its dial. But your idea of its 'works' (unless you are a clockmaker) is much less of a copy, yet it passes muster, for it in no way clashes with the reality. Even though it should shrink to the mere word 'works', that word still serves you truly; and when you speak of the 'time-keeping function' of the clock, or of its spring's 'elasticity', it is hard to see exactly what your ideas can copy.

You perceive that there is a problem here. Where our ideas cannot copy definitely their object, what does agreement with that object mean? |

|

|

|

We might summarise this view by saying that for William James there are two kinds of statements: (1) the smaller class consists of statements where it is plausible to make some kind of direct correspondence to reality, for example, the picture of a clock corresponds to the clock; (2) the larger class consists of statements where it is not plausible to make a direct correspondence to reality, for example, the time-keeping function of the clock does not correspond to any particular collection of sensory experiences.

|

|

|

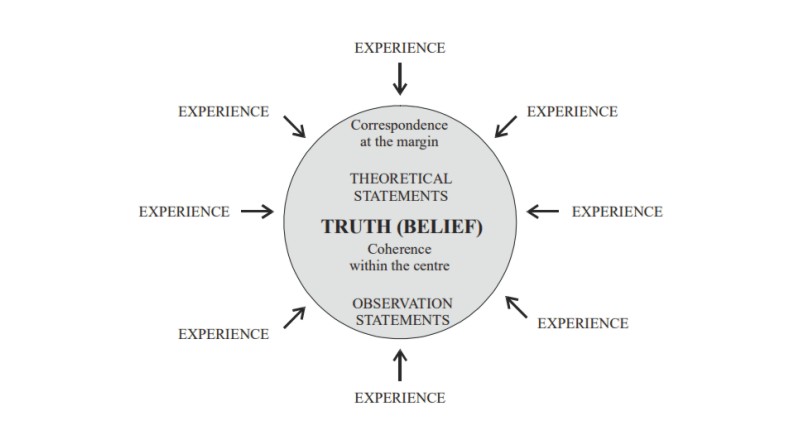

What most modern pragmatists seem to hold regarding the relationship between truth and reality is something that could be called the Quinian model of truth after W.V.O. Quine who advanced it in his essay Two Dogmas of Empiricism. We will simplify it here. It proposes a kind of “onion” type theory of truth. Truth is like an onion, and at the outer most layer there is a correspondence between statements (beliefs) and experience; but once we pass inside the onion the correspondence breaks down; what we have on the inside is a web of statements that cohere with each other.

|

|

|

|

|

The Quinian (pragmatist) model of truth

|

|

|

In the end the total system of beliefs is justified by a mixture of its coherence within the system and its correspondence on the periphery with experience.

|

|

|

Pragmatism is opposed by positivism. Pragmatists recognize that there is a degree of correspondence between observation statements and the observations themselves, however positivists would extend the notion of correspondence to cover a relationship between all meaningful statements and reality, even when that reality cannot be directly observed. Although atoms are not and never will be directly observed [Even if a microscope was built that enabled “atoms” to be “seen”, what one would be seeing would be an image of something which would be interpreted as the image produced by an atom. The atom remains a theoretical entity, and one that is never directly observed.] for positivists atoms nonetheless exist, and always have existed. Pragmatists tend to regard entities only as existing in so far as a theory allows them to exist, and to maintain that theories bring entities into existence.

|

|

|

Pragmatists evaluate theories according to their practical consequences. William James explains this as follows.

|

|

Pragmatism ... asks its usual question. “Grant an idea or belief to be true,” it says, “what concrete difference will its being true make in any one's actual life? How will the truth be realized? What experiences will be different from those which would obtain if the belief were false? What, in short, is the truth's cash-value in experiential terms?”

The moment Pragmatism asks this question, it sees the answer: True ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate and verify. False ideas are those that we can not. That is the practical difference it makes to us to have true ideas; that, therefore, is the meaning of truth, for it is all that truth is known as.

This thesis is what I have to defend. The truth of an idea is not a stagnant property inherent in it. Truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made true by events. Its verity is in fact an event, a process: the process namely of its verifying itself, its veri-fication. Its validity is the process of its valid-ation.

[William James:Pragmatism's Conception of Truth.] |

|

|

|

It is usual to link this idea of pragmatic verification with the idea of utility, and William James is responsible for this link.

|

|

| The practical value of true ideas is ... primarily derived from the practical importance of their objects to us ... You can say of an extra truth ... either that 'it is useful because it is true' or that 'it is true because it is useful'. Both these phrases mean exactly the same thing, namely that here is an idea that gets fulfilled and can be verified. True is the name for whatever idea starts the verification-process, useful is the name for its completed function in experience. True ideas would never have been singled out as such, would never have acquired a class-name, least of all a name suggesting value, unless they had been useful from the outset in this way. [William James: Pragmatism, lecture VI.] |

|

|

|

However, it is debatable whether the concept of “useful” should be connected with the notion of “utility” in an ethical theory such as utilitarianism. What is useful is what can be assimilated into the body of theory as a whole; it is that theory, and the way we live in relation to that theory, that characterises what we regard as useful. In the end, what is useful is what helps us to interpret experience.

|

|

|

Some modern theorists, such as Quine, seek to use this theory of Pragmatism to complete the Positivist's desire for a clear demarcation between science and non-science. Such a demarcation would serve to show that all non-scientific notions can be rejected as untrue, since they cannot be assimilated into a coherent interpretation of experience. However, this application is not necessitated by Pragmatism as such. William James did not, himself, seek to eliminate religious hypotheses and entities as incapable of being fitted into a coherent and useful interpretation of life. This is made clear in the following extract.

|

|

Theism and materialism ... point, when we take them prospectively, to wholly different outlooks of experience. For , according to the theory of mechanical evolution, the laws of redistribution of matter and motion, though they are certainly to thank for all the good hours which our organisms have every yielded us and for all the ideals which our minds now frame, are yet fatally certain to undo their work again, and to redissolve everything that they have once evolved...

The notion of God, on the other hand, however inferior it may be in the clearness to those mathematical notions so current in mechanical philosophy, has at least this practical superiority over them, that it guarantees an ideal order that shall be permanently preserved. [William James: Some Metaphysical Problems Pragmatically Considered..]

|

|

|

|

James regards the content of the notion of “God” as expressed in its practical consequences. It is a possible constituent of a future scientific theory. His pragmatic theory dissolves the boundary between science and metaphysics.

|

|