|

Descartes - Meditation I and the Method of Doubt |

I. Outline of the First Meditation |

|

In this Meditation Descartes begins by introducing the method by means of which he will seek for certain truth. He seeks to build knowledge up from a secure and certain foundation — this is called the axiomatic method. Having stated his goal, he proceeds to argue for a pre-emptive scepticism that will serve to refute empiricism as a possible foundation for knowledge. That scepticism is based on the method of doubt, which he introduces. He then offers three particular sceptical arguments of increasing severity: (1) an argument based on sense-deception, sometimes called the argument from illusion; (2) an argument based on dream scepticism; (3) an argument known as the evil genius argument. Since the evil genius argument involves considering the possibility that God does not exist, before he introduces it he offers a “disclaimer”, saying that no serious consequence could follow from considering this idea.

|

|

II. Axiomatic method |

|

Descartes writes:

|

|

| I became convinced that it was necessary once in my life to undertake to eliminate every mere opinion I had come to accept as true, and begin again to build [knowledge] from the foundations upwards, in order to establish a firm and lasting construction of scientific truth. |

|

|

|

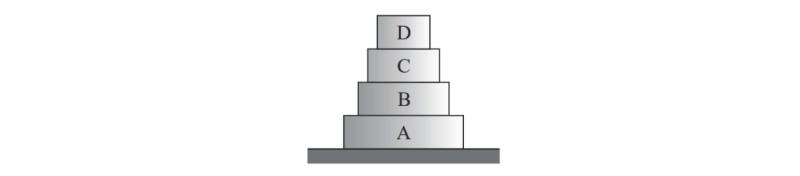

In order to understand this sentence fully you need to understand a good deal about logic and logical inference. In outline, Descartes imagines building up knowledge in much the same way that a child might make a tower of building blocks.

|

|

|

|

|

The child cannot construct the tower if he does not have a firm and level surface on which to build; by analogy, knowledge cannot be established, unless there is a foundation for knowledge.

|

|

|

Logical inferences proceed from premises to conclusions. For example,

|

|

|

|

|

This is a famous example of a formal logical inference, (a deduction), given by Aristotle in his theory of logical inference called the syllogism.

|

|

|

This is a deductive inference. It works by bringing a “minor” premise (“Socrates is a man” under a “major” premise (“All men are mortal”). Since the minor premise correctly falls under the major premise, the conclusion is held to follow of necessity. The logical inference is a kind of force that compels the person who contemplates it to agree to the conclusion, provided that he already accepts the premises as true.

|

|

|

One aspect of a deductive inference that is important is that the conclusion can never have more generality that the premises (taken altogether). For this reason, deductive inference is a process of analysis. You create new conclusions but only by extracting the information already contained in the premises.

|

|

|

The above argument could be represented in a more schematic (algebraic) way, as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

Here I am using the letter A to stand for all the premises, and the letter B to stand for the conclusion.

|

|

|

I could imagine building up a chain of inferences through successive deductive arguments. I could represent this thus:

|

|

|

|

|

This method could lead to a vast systematic organisation of my knowledge, and it is this possibility that was exciting Descartes at the time of writing the Meditations.

|

|

|

As the diagram indicates, the conclusions would be built up successively from a starting point, A. The starting point, A, would be an axiom.

|

|

|

An axiom is an assumed starting point for a chain of deductive reasoning.

|

|

|

Descartes is drawing upon the experience of an earlier attempt to organise mathematical knowledge along these lines. In the third century BC the famous mathematician Euclid wrote a treatise, in which he deduced the entire body of Greek knowledge about mathematics from just five axioms. His work, The Elements has been published in more editions than any other work in the whole history of mankind, which is an indicator of its importance in the history of ideas.

|

|

|

During the dark ages The Elements had been lost, but in the time of the Renaissance, during which Descartes lived, it was rediscovered. It made a profound impact on the thinking of renaissance scholars.

|

|

|

Descartes was fascinated by the prospect of being able to organise all philosophical knowledge along the same lines. The Meditations is his first attempt to do so. In later works, most notably The Principles of Philosophy, he claimed to be able to derive the entire body of current scientific knowledge from just one axiom, which we shall see in Meditation II is his famous Cogito.

|

|

|

We can compare this idea of the chain of deductive inferences to the building block picture we have already introduced.

|

|

|

|

|

This picture indicates the first problem introduced by such a method. That problem is that, just as you cannot build a tower without a fixed and firm surface, so you cannot build a deductive superstructure of knowledge without a foundation for knowledge.

|

|

|

It may just be that there is no foundation for knowledge, and that all that we call knowledge is a collection of ideas that we relate by logical arguments, but nowhere finds a basis. This theory is in fact called the coherence theory of truth and is advocated (arguably) by Wittgenstein among others; in any case, it is by no means agreed that there is a foundation for knowledge, or that if there is, that knowledge can be organised in the way that Descartes assumed it could.

|

|

|

That, of course, is one of the criticisms of this approach. Descartes will go on to argue in favour of an all-embracing scepticism; but if that scepticism is genuinely all-embracing, it should encompass also doubt as to his own method. He never does question the possibility that his quest for a foundation is actually erroneous, and that there is no foundation.

|

|

|

Denying the existence of a foundation is one way in which to question Descartes’ method here.

|

|

|

Let us suppose, for the present, that there is some kind of foundation to knowledge. Then, we must see that this foundation to knowledge could not itself be the result of a deductive inference. If it were, this would derive the foundation of knowledge from other premises, which would in turn need a foundation. In other words, we would be led into a infinite regress, seeking again and again the foundation for the foundation of the foundation; and so forth.

|

|

|

So the foundation for knowledge, if there is one, must rest on a basis that is different in kind from anything that is subsequently deduced from it.

|

|

|

The foundation must be made up of one or more true statements that are self-evidently true. If they are self-evidently true, then their truth must be guaranteed by a direct form of perception of the mind. The mind must just see that it is true.

|

|

|

There has been in the history of ideas three alternative solutions to what this foundation is, and what the relationship of the mind to it could be:

|

|

| 1 | | Empiricism

This asserts that the foundation for knowledge is sense-experience.

| |

| 2 | | Rationalism

This asserts that the mind has an extra-sensory faculty called reason that enables it to grasp ideas that are not derived from sense-experience, which are consequently called innate ideas.

|

|

| 3 | | Existentialism

This asserts that the mind has to choose what to believe, and that the foundation for knowledge is an act of will, whereby each individual decides for him or herself what he or she regards as self-evidently true. The existential act of choosing is also, in the broadest sense, an act of faith. Therefore, this philosophy asserts that faith is the foundation for knowledge, and for living.

|

|

|

|

Existentialism shall not be pursued here.

|

|

|

In this first Meditation Descartes wishes to prove to us that empiricism is false, and hence demonstrate that the only possible theory of knowledge is rationalism.

|

|

|

Before we proceed to examine Descartes' arguments in favour of this conclusion, it may be as well to look at some terminology that is used in relation to this discussion.

|

|

|

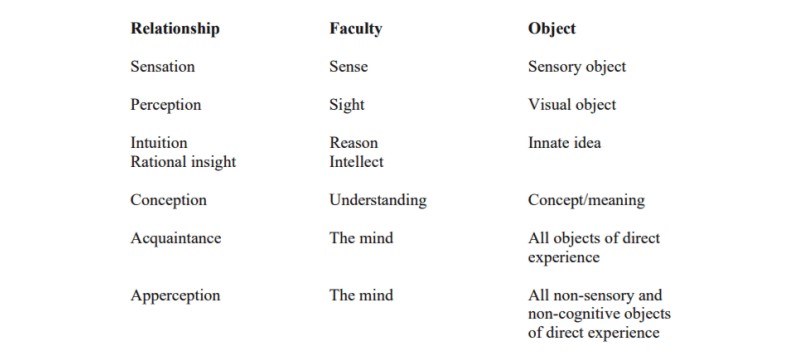

Empiricists, as already indicated, assert that all knowledge is derived from sense-experience. Objects of sense-experience are presented through the five external senses. We use the term sensation to denote the relationship between the mind (awareness) and any object of sensory experience. We use the term perception for the relationship of sight. However, typically of the English language, the term perception is sometimes used to denote the relationship of sensation as a whole; that is, it is possible to meet the term perception where otherwise sensation could be used.

|

|

|

Also sensation does not strictly cover just what we experience through the five external senses. Hume correctly distinguished internal from external sense. We have a faculty of proprioception, which is the capacity to sense our position, location, orientation and movement of our own bodies. Furthermore, we have the ability to feel pleasure and pain; whilst these may be occasioned by sensations, they are not identical to them; also we have emotions, and these too are given to internal sense.

|

|

|

However, the existence of internal as opposed to external senses is not generally thought by empiricists to overturn their doctrine that all knowledge comes through the senses. These internal senses are thought to be of the same kind as the external senses, only pointing inwards as opposed to outwards.

|

|

|

As already indicated, rationalists do not agree that sensation is sufficient to cover all the capacities of the mind to relate to objects. They believe in the existence of ideas that cannot be derived from sense-experience. Rationalists generally use the term intuition for the relationship between the mind (awareness) and ideas. The term intuition can also be used in a generic sense, in other words, to cover all intuitions of innate ideas and sensations as well. So the phrase “everything given to intuition” could encompass all ideas and all perceptions.

|

|

|

Descartes uses the terms rational insight, rational intuition and clear and distinct perception to denote this relationship between the mind and ideas.

|

|

|

An idea that is understood, in other words, that acts as a sign signifying a meaning, is called a concept. It is also called a meaning. The terms understanding and conception are sometimes used to denote the relationship between the mind and a meaning. The faculty that grasps meaning is also sometimes called intellect or reason.

|

|

|

All of these philosophies assert that the mind has the capacity for a direct relationship between the mind (awareness) and objects of awareness, whether they are sensory objects or concepts. Thus, the term acquaintance is also used in some contexts to denote the general relationship of this direct experience of objects presented to awareness (consciousness).

|

|

|

One can also meet the term apperception used either in a generic sense to denote the intuition of anything directly given, rather like acquaintance, or in a specific sense to denote the direct experience of something which is not a sensory object but yet might not qualify as a concept, such as the apperception of the self, or of space and time.

|

|

|

In summary, we have:

|

|

|

|

III. Method of Doubt |

|

Descartes writes:

|

|

| But even now my reason convinces me that I ought to take care to withhold my belief from what is not entirely certain and beyond doubt just as I withhold my belief from what is manifestly false; so I shall find sufficient reason to justify rejecting all [of a class of propositions] if there is ground for doubting some [of the propositions of that class]. |

|

|

|

What this says is that if there is any way in which I can imagine that something I think I know is not true, then I do not know for certain that it is true.

|

|

|

This principle, which is the basis of his method of doubt, makes an assumption about the meaning of to know which is itself capable of being questioned.

|

|

|

Although Descartes never explicitly states what he thinks to know means, we have come to call his assumptions about the meaning of knowing the “Cartesian concept of knowledge”. There are two distinctive elements to this concept.

|

|

|

1. To know means to know for certain.

|

|

|

If you know something then you could not possibly be wrong about it.

|

|

|

2. Knowledge is true, justified belief

|

|

|

(This second statement is known as the tripartite theory of knowledge.) You do not know something unless you have a fail-safe method of justifying that you know it. The method must guarantee that what you know is both true and certain.

|

|

|

The statement “knowledge is true, justified belief” also says that “knowledge is belief”. However, this is generally accepted by everyone; that is, it is agreed that all people use the term to know in contexts in which they would say they believe what they know. Knowing is a form of believing.

|

|

|

The term “true” in the statement “knowledge is true, justified belief” is redundant (that is, strictly not needed). The reason why is because the process of justification should guarantee that what is known is true; therefore, it ought to be enough to say, “Knowledge is justified belief”.

|

|

|

Both parts of the Cartesian theory of knowledge can be challenged. Hume opposes both, and Hume's arguments have been further supported in more modern times by Wittgenstein in his attack on Descartes' method in his book On Certainty.

|

|

|

At first, Descartes' theory may seem to be obvious and compelling. However, on closer examination we can see that there is at least an alternative theory of what knowing is that is equally plausible. We shall argue that the assumption of Descartes' theory is equivalent to assuming rationalism, and hence the whole of Descartes' philosophy is circular — it assumes what it has to prove.

|

|

|

To see why, let us first describe an alternative theory, which is suggested by Hume in his Treatise.

|

|

|

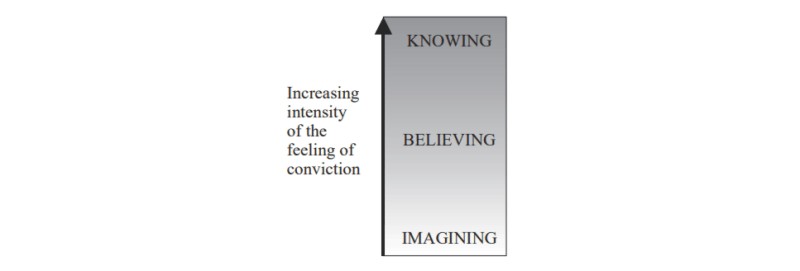

Firstly, Hume argues that beliefs come in degrees of intensity. In other words, the ideas one contemplates in a belief can be either more or less forceful. In fact, a weak belief might be taken for a figment of the imagination.

|

|

|

What this means is that there is nothing that is believed that is not subject to some element of doubt. Of course, when one believes something strongly one does not entertain the possibility that it could be false; to believe means to believe something is true. However, this is a fact of psychology, and viewed logically everything that is believed is capable of some error. Another way of putting this, is that everything believed is merely probable.

|

|

|

But likewise, knowledge is also a matter of probability.

|

|

|

In conclusion, there is no great dividing line between knowing and believing. Perhaps we use to know in contexts that imply a very strong belief, but knowledge and belief belong to the same species, and both are statements of what is merely probable. Imagining, believing, knowing come in degrees of intensity; we could, perhaps, make a theory of this according to the following diagram.

|

|

|

|

|

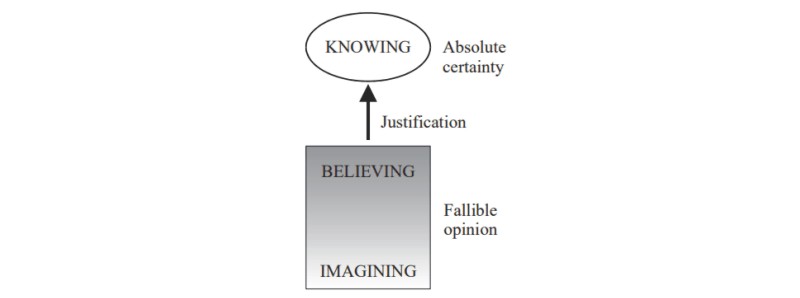

Hence, the contrast with Hume's theory. Descartes does create a dividing line between knowing and believing. Believing is prone to error; beliefs are mere opinions. But what is known is known for certain; in other words, the process of justification that goes with knowing guarantees certainty and infallibility.

|

|

|

|

|

Now that we have seen Hume's alternative to Descartes' theory we can explore more successfully the implications of Descartes assumptions. Could knowledge gained through sense-experience ever acquire such force as to be utterly infallible? The answer to this is plainly no. Sensory information may be very compelling, yet there is nothing that is seen with the eyes that is not capable, upon some outlandish supposition, of being actually false. Suppose I am looking out of my window at my car parked below. I may say with a high degree of confidence that my car is parked in front of my house. But it is just possible that someone has stolen my car, and replaced it by a car that looks just like it; whilst this is not likely, it is possible. In other words, nothing that is given through sense-experience could be certain in the sense that what is certain could not possibly be false.

|

|

|

Putting it another way, to assume the Cartesian concept of knowledge is to assume that it is meaningful to talk of a state of mind in which you have attained infallibility. Since such infallibility could not be attained through sense-experience, it could only be attained by means of an extra-sensory power of the mind, which it is usual to call reason that enables one to know things independently of sense-experience.

|

|

|

Hence, the Method of Doubt assumes the Cartesian concept of knowledge, and that in turn assumes that there exists an extra-sensory power of the mind, which we call reason, that enables us to know things independently of sense-experience.

|

|

|

It might be objected that the Cartesian concept only shows us that the concept of knowledge is distinct from that of mere believing, and does not assume that there is anything that we know for certain. However, the concept of knowledge must be derived from some source, and since sense-experience cannot be that source, to acknowledge that the Cartesian concept of knowing is meaningful is already to step along the path that leads to rationalism.

|

|

|

On the other hand, do we have any method that enables us to decide whether to know means to know for certain or not? G.E. Moore, who was defending the empiricist view of knowledge, wrote an essay in which he argued that no body ever does actually use to know in common language in the sense that Descartes implies. However, even if Moore is right, it is not a proof that there is no meaningful Cartesian concept of knowledge, since the Cartesian would argue that what “common people” say and do is not important to philosophy.

|

|

|

The rationalists' strongest argument concerns demonstrating that there are forms of knowledge that could not be derived from experience — knowledge of meanings, universals, mathematics and logic are among their examples. This argument, known as the transcendental deduction is pursued in another unit.

|

|

|

To reject Descartes in favour of Hume (and Wittgenstein) is a possibility; but it is equally possible to be convinced that Descartes is right! We have reached an impasse typical of philosophy. Actually, what we have is two relatively complete systems of thought, the empiricist and the rationalist, and both have a degree of inner consistency.

|

|

IV. Sense deception — the “argument from illusion” |

|

Descartes writes:

|

|

| Up to now everything that I have accepted as possessed of the highest truth and certainty I have acquired either from or through the senses. However, I observed that these [senses] sometimes deceive us; and it is prudent not to place absolute confidence in anything that has deceived us even once. |

|

|

|

This argument is related to an argument in philosophy known as the “argument from illusion”. That is an argument that has provoked considerable controversy, and is also left for discussion in another unit. Descartes' statement here of his argument is vague and lacks illustration, although later in the Meditations he does offer some examples of what he means by illusions. We will approach our critique of this statement from two contrary points-of-view: firstly, we shall examine what a thorough-going empiricist would say at this juncture; but secondly, we shall examine what a subsequent proponent of the “argument from illusion” might also wish to add to Descartes' statement here.

|

|

|

One approach that the empiricist might adopt is to argue that it is not the senses that deceive us, but that our judgement regarding our sense-experience is sometimes in error. There is a tradition in modern philosophy advanced by Russell and Ayer that the primary objects of sense-experience are sense data, tiny, indivisible “atoms” of perception and sensation given directly to consciousness. These sense data are not in any way erroneous. They are the stuff out of which perceptual judgements are made, but are not the result of any conscious or unconscious intervention in perception. They are just given. Since they are just given, they are not the source of error. Error arises when judgements are formed on the basis of the sense data. The fact that sometimes perceptual judgements are faulty does not in any way prove that the senses cannot be trusted. In fact, in order to show that a perceptual judgement is mistaken — such as mistaking a mirage for a real object — one has to be able to compare that judgement to one that is accurate, so in this way, all illusions presuppose real and valid perceptual judgements. Thus, so far as anything can serve as the foundation for knowledge, sense data do qualify.

|

|

|

So much for an empiricist “answer” to this argument; we now turn our attention to what later rationalists (and idealists) might wish to add to Descartes' argument.

|

|

|

Sense-deception is often advanced in the context of sceptical arguments concerning our knowledge of external reality. Descartes is attacking the senses in general, and not specifically our belief in the existence of a material reality that is independent of our consciousness. However, that is what an idealist would argue he should be doing here. There is a confusion running throughout Descartes' Meditations regarding the concept of what an external reality might be. There are two senses of what is real, and they contradict one another. In one sense what is real is what is immediately given to sensation; in another sense what is real is what exists independently of consciousness. The idealist critic of Descartes would argue that he persistently fails to make a distinction between what is directly present to the mind, such as sense experience, and what may be thought of as existing independently of the mind. An idealist would argue that had Descartes been more consistent in his treatment of this issue, he would have been led by this argument to the idealist conclusion that what is real in the sense of being external to consciousness is always unknown and unknowable. This objection to his form of the sense-deception argument could, if carried forward, lead the objector towards idealism. Of course, there are also realists who acknowledge that there is a distinction between perceptions that exist only when perceived and the unperceived cause of perceptions, the real world that exists independently of all consciousness whatsoever. However, it is not possible to support such realism on the ground that we directly perceive in sense experience real objects.

|

|

|

The idealist is not obliged to reject sense experience as a source of knowledge. Descartes in attacking the senses is not merely seeking to establish what is the foundation of knowledge.

|

|

|

Descartes is influenced by the philosophy of Plato, and by Plato's attack on the senses as a source both of falsity and moral corruption. Although ethical considerations are never directly mentioned by Descartes, it seems clear that Descartes draws exclusively on the Platonic tradition that man is in a fallen state, and that the source of his corruption in this life is the craving for sensory objects; these stimulate desire and prevent the mind from dwelling on purely intellectual matters. Descartes' attack on the senses must be read in conjunction with a study of the ideas of Plato.

|

|

|

This sceptical attack on the senses is Descartes' first application of his Method of Doubt. He is offering a “pre-emptive” scepticism, because it is intended only to act as a preliminary to clear the way for the (rational) reconstruction of knowledge starting from an indubitable axiom, which it is the task of the method of doubt to discover, namely the cogito.

|

|

V. Dream Scepticism |

|

Descartes' second attempt to attack sense-experience as a source of knowledge is given here

|

|

| However, I must note that I am only human, and consequently that I habitually sleep, and that in my dreams I have images of those same things, or even of more improbable things, that insane people see when they are awake. How many times have I dreamt during the night that I was in this room by the fire, whereas in fact I was asleep, naked in my bed? It seems certain just now that I am not looking at this paper with closed eyes; that as I shake my head I am not asleep; that when I deliberately and intentionally hold out my hand, I am aware of it. The images presented in dreams are not so clear and distinct as these are. Yet, on reflecting more carefully about all of this, I remember that I have often been deceived in my sleep by similar illusions, and thinking even more closely, I conclude that there is nothing that conclusively and clearly distinguishes between waking and sleeping. I am quite amazed at this, and I feel so astonished that I am almost convinced that I am actually asleep right now! |

|

|

|

There are two questions raised by dream scepticism: (1) do dreams force us to accept that there is a distinction between what is directly given to consciousness and what is not? (2) Is it in fact impossible to tell the difference between dreaming and waking?

|

|

|

The two questions are not necessarily related, although it is a popular confusion, which Descartes supports in this passage, to think that they are. The second question concerns the distinction between two states of consciousness, and it is not necessary to be able to assert that waking images correspond to real objects existing independently of consciousness, whilst dream images do not, in order to be able to answer it. Later on in the Meditations Descartes acknowledges that it is possible to distinguish between waking and dreaming. He writes in Meditation VI:

|

|

| I now note that there is a very significant difference between the two states [of waking and sleeping], for our memories are unable to make connections between one dream and another, or between a dream and the events of life in the same way that it is between the events that occur when we are awake. |

|

|

|

Once again this is vague, and we can in fact do better. The features of dream experiences that make them different in kind from waking experiences are as follows: (1) Waking experiences are connected by causal laws, that is patterns of regularity that conform to rules regarding such things as gravity, continuity of motion, conservation of energy and so forth. In dreams causal laws are suspended. It is quite possible in a dream for an object to disappear entirely, for people to fly, and so on. It is on this basis that we (unconsciously) judge one kind of experience to belong to the dream world, and another kind of experience to belong to waking reality. (2) In dreams our potential to do things is increased, but our control over our actions is decreased. We experience our faculties in a different way. For example, in a dream I might be able to fly, but I might also not be able to choose whether to fly. This contrasts with waking experience, when, for instance, I have the power to raise my arm, but not to fly, but the movements of my arm are subject to my will. As an aside, it is worth remarking that these qualities of dreams support the theory that dreams are expressions of our wishes and anxieties. The increased potential to do things (for example, to fly) expresses wish fulfilment; the inability to control events, including our own actions, expresses our anxieties over loss of control. (3) The perspective in dreams can sometimes be altered. People report in dreams “out of body” experiences. It is arguably not essential to perceive everything that happens in a dream as related to a centre of perception that is the ego.

|

|

|

It is quite possible when waking to ask oneself whether one is dreaming, and the answer is usually quite clear — no I am not dreaming now! It is less commonplace to ask oneself in a dream whether one is dreaming, but this also can occur. There are such things as lucid dreams in which the dreamer knows that he is dreaming whilst in the dream state.

|

|

|

In conclusion, it is possible to distinguish dreaming from waking as different states of consciousness.

|

|

|

However, it is a common assumption that waking experiences correspond to real events and are signs of objects that exist independently of consciousness; whilst dream experiences are entirely subjective in their origin, and that what is perceived in a dream is not the product of an external object, and so forth.

|

|

|

Since both dream images and waking images are merely objects presented directly to consciousness, it is arguable that there is no certain proof that dream images do not correspond to real things, whilst waking images do. Solving the problem of what distinguishes dream images from waking images does not resolve this problem. In this sense, dream scepticism is just another example of an illusion, and this topic is also discussed in another unit in relation to the “argument from illusion”.

|

|

|

VI. The “Evil Genius” argument |

|

Descartes concludes the First Meditation by considering the possibility that some malicious devil, who is both extremely powerful and a liar, has exercised all his skill in deceiving him.

|

|

|

This effectively considers the possibility that the universe is governed by a devil. That is equivalent to considering the possibility of devil worship. Presumably, that is what devil worshippers actually believe — that there is a supernatural power that is evil and powerful and not subject to the will of a higher power that is good and yet more powerful. Another possibility that Descartes could be entertaining here is the doctrine of Manichaeism, that there exists both a God and a Devil, and that both are equal and opposite powers, destined to battle it out for all time. Descartes supposition is also tantamount to considering the possibility of atheism - that there is neither a God nor a devil, and just a reality that is governed by laws that are independent of consciousness.

|

|

|

Given the context in which Descartes was writing these are brave thoughts indeed, and Descartes is aware that there could be a religious backlash. Consequently, he disguises the full implications of his radical argument by giving a lengthy (and boring) preamble, which also contains the following “disclaimer”.

|

|

| I am sure that my intention [to subject everything to doubt by considering even propositions that would normally be injurious to faith] will not lead me into any danger or error, and that I should at this time give way to every source of doubt, since my purpose is not action but knowledge. |

|

|

|

This is not strictly valid. How can we know the end of an enquiry before we have reached it? Descartes is, of course, confident. By the time of writing, he has already completed the course of the six meditations, and as far as he is concerned the threat posed by such radical questioning does not lead away from faith and a belief in God. He is reporting with the benefit of hindsight, knowing already the path and where it leads. But if he is genuinely reporting a journey that he has undertook, there must have been a point at the outset of the journey when he did not know the outcome — that is, assuming Descartes was sincere in his willingness to entertain all forms of scepticism!

|

|

|

In the Enquiries Hume replies as follows to this form of scepticism

|

|

| There is a species of scepticism, antecedent to all study and philosophy, which is much inculcated by Descartes and others, as a sovereign preservative against error and precipitate judgement. It recommends an universal doubt, not only of all our former opinions and principles, but also of our very faculties; of whose veracity, say they, we must assure ourselves, by a chain of reasoning, deduced from some original principle, which cannot possibly be fallacious or deceitful. But neither is there any such original principle, which as a prerogative above others, that are self-evident and convincing; or if there were, could we advance a step beyond it, but by the use of those very faculties, of which we are supposed to be already diffident. The Cartesian doubt, therefore, were it ever possible to be attained by any human creature (as it plainly is not) would be entirely incurable; and no reasoning could ever bring us to a state of assurance and conviction upon any subject. |

|

|

|

This is also an attack on Descartes claim that his cogito is sufficient to extricate himself from the scepticism created by this argument. When we consider the cogito we shall in fact argue that Hume is right in this matter, and that the cogito is not a sufficiently powerful argument to retrieve one from scepticism, should the evil genius argument have already forced one into it.

|

|

|

The evil genius argument is a further example of a prototype statement of another variety of scepticism — the problem of “entrapment within subjectivity”. All our experiences, everything that happens to us, are experiences presented to a subjective consciousness. The evil genius argument focuses our attention on the problem of whether we can be sure that any subjective experience corresponds to an objective reality. The real problem expressed by it is the problem of our not knowing what the world looks like except through our own eyes.

|

|

|

However, to formulate the argument one must be prepared to accept the Cartesian concept of knowledge with its distinction between a higher state of mind, of knowledge and a lower state of mind of mere believing. If such a distinction cannot be drawn, then it is an error to think that we can force our consciousness into such a condition so as to be able to consider seriously that everything before us is an illusion. The attack on the evil genius argument is the same as the attack on the Cartesian concept of knowing.

|

|

|

Empiricists tend to deliberately blur the distinction between what is subjective and objective. They ask us to take things as they appear to be. To be sure, there are occasional situations in which the senses are deceived — a stick that is straight appears bent in water — but really these occasions just serve to reinforce the fact that in the majority of cases we just get it right. For them objectivity is achieved by rigorous application of the scientific method to the observation of sense-experience. There is no metaphysical distinction here between a subjective reality as it appears to consciousness and an objective reality that is not given to consciousness. The objective is reached through examination of sense-experiences that are also the stuff of subjective perceptions.

|

|

|

To an idealist, who draws a thorough going distinction between what is real in the sense of directly experienced, and real in the sense of independent of consciousness, the empiricist's attempt to leave things as they are seems naïve.

|

|

|

Finally, by means of the “evil genius” argument Descartes seeks specifically to undermine our confidence in mathematics and logic. It could be argued that Descartes has not genuinely shown us that mathematics and logic could be doubted. His approach contrasts with that of Kant, who takes mathematics and knowledge of forms of certain knowledge, and then seeks to explain how we come by this certainty.

|

|

[i] We are frequently in doubt concerning the ideas of memory, as they become very weak and feeble; and are at a loss to determine whether any image proceeds from the fancy or the memory, when it is not drawn in such lively colours as distinguish that latter faculty. I think, I remember such an event, says one; but am not sure. A long tract of time has almost worn it out of my memory, and leaves me uncertain whether or not it be the pure offspring of my fancy.

And as an idea of memory, by losing its force and vivacity, may degenerate to such a degree, as to be taken for an idea of the imagination; so on the other hand an idea of the imagination may acquire such a force and vivacity, as to pass for an idea of the memory, and counterfeit its effects on the belief and judgement.

. . . Thus it appears, that the belief or assent, which always attends the memory and senses, is nothing but the vivacity of those perceptions they present; and that this alone distinguishes them from the imagination. (Hume, Treatise of Human Nature, Book I, Part III, Section IV:Of the impressions of the senses and memory.)

|

|

|

[ii] ... all knowledge degenerates into probability; and this probability is greater or less, according to our experience of the veracity or deceitfulness of our understanding, and according to the simplicity or intricacy of the question. (Hume, Treatise of Human Nature, Book I, Part IV, Section I:Of scepticism with regard to reason.)

|

|

|

|