|

Subjectivism versus Objectivism |

I. The meaning of the terms subjective and objective |

|

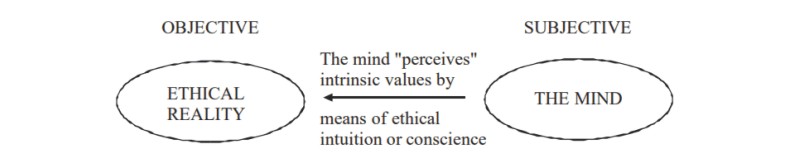

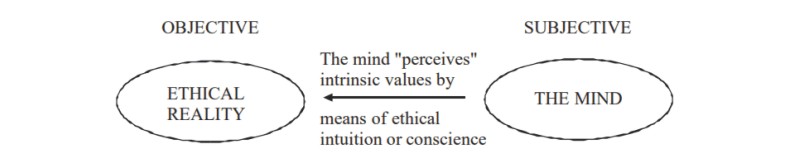

One of the central meta-ethical issues concerns the question of whether ethics is subjective or objective. We are being asked to compare ethical judgements with factual ones, and to decide whether they have a similar status. It is usual in this debate for philosophers to assume the existence of an external reality and appraise ethical statements on the assumption that there is a real world of physical objects. If ethics is objective then there must exist an objective moral reality that renders ethical statements true. On an analogy with sense-perception, the mind would be equipped with a special moral faculty of perception. This is often called moral intuition, but may also be interpreted by some to be our conscience. Goodness, rightness, would be regarded as real properties either of things, or of actions.

|

|

|

|

|

If ethical reality exists then it is a non-material reality. Consequently, the manner in which the mind perceives it — by conscience or ethical intuition — would have to be non-material and non-mechanical.

|

|

|

If ethics is subjective, then ethical statements are statements of feeling only. These feelings are held to arise in the subject only, and do not correspond to any properties in reality, physical or otherwise.

|

|

|

|

|

Physical reality may cause these subjective ethical feelings to arise. In the language of Locke, moral feelings are regarded decidedly as secondary qualities.

|

|

|

The current trend in our society is towards subjectivism. Objectivism is associated with the belief in God. However, there are three views on this matter, all of which might be objectivist.

|

|

| 1 | | There exists an objective moral reality and God, and they are both distinct. |

| 2 | | There exists an objective moral reality, and God, but in point of fact they are identical (in some sense). |

| 3 | | There exists an objective moral reality, but no God. |

|

|

|

The first view is advanced to an extent by Plato. He claimed that there exists a ultimate reality made of forms and that these forms are true, beautiful and good. In his dialogue The Timaeus he goes on to state that there was a demi-urge who fashioned the prima materia of the universe in the likeness of the forms. In this way God is seen to be subordinate to ethical reality.

|

|

|

However, the tendency in Christian thought is to equate God with moral reality. This doctrine is not stated as such in Christian theology but is rather implied by the Christian identification of what is right as obedience to God's commands as dictated through conscience or by authority, and also what is sin as disobedience. This tendency can be seen in this quotation from St. Augustine's On Free Choice of the Will.

|

|

| For if there is something more excellent than the truth, then that is God; if not, the truth itself is God.

|

|

|

|

Preliminary arguments in favour of subjectivism might include: (1) The belief that moral properties are not to be found in reality. This in a way “begs the question” because it rules out before consideration the possibility that a separate moral reality does exist. However, “goodness” is felt to be a different kind of property from, say, “length”, and not one that exists really in the object that we perceive. And yet, in a way, we do perceive certain objects as good. In order to account for this subjectivists argue that the experience of goodness is projected onto the image of the object by the mind. (2) Subjectivism is supported by a belief in materialism; indeed, materialism entails subjectivism. The existence of another reality, and most especially of a non-mechanical faculty of perceiving it, is felt to be intuitively implausible. (3) Many people feel that ethics is just a matter of feeling, whereas they do not have any idea what “moral intuition” might be. This, however, could be regarded as an error of conception. It is questionable whether any vision (that is a quasi-perception), for example, could constitute an intuition of moral reality. The moral feelings that we may have may be just what it means to intuit moral truths.

|

|

|

Thus these “preliminary” arguments all tend to assume subjectivism rather than prove it. That morality is a matter of feeling may be true, but the question is, are these feelings statements only of our subjective nature, or are they the manner in which we communicate with an objective moral reality? Subjectivism accords with the materialism of the current age, but the question is, is that materialism justified? The objectivity of ethical feelings would disprove materialism.

|

|

|

One attempt to “prove” the subjectivity of values is through the so-called “argument from relativity”.

|

|

II. Argument from Relativity |

1. Everyone disagrees about values.

2. Therefore, There cannot be any objective values.

|

|

|

The argument from relativity is the argument that because everyone disagrees about what is right and good, then ethics must be subjective. It is generally agreed that this is a fallacy.

|

|

|

That subjectivism might be a cause of disagreement is true, but for an argument to be sound the conclusion must necessarily follow from the premises. In this case, there are other ways in which the disagreement could arise that do not involve subjectivity.

|

|

| (1) | | One party to the disagreement could simply be wrong; this may be due to willful blindness (self-deception), or it may be due to the lack of or weakness in the moral faculty (on analogy with blindness and bad slight). |

| (2) | | Relativity is a possibility. A truth is absolute if it is true for all observers whatsoever. If the truth of a statement varies from one point-of-view to another, then it is relative to that point-of-view. However, both relativism and absolutism are objective accounts of the nature of a class of statements. |

|

|

|

This latter point may need some explanation. Firstly, let us illustrate what the concept of relativity means. Suppose you are on a train that is just pulling away from the station. From your point-of-view the objects inside the compartment where you are sitting are not moving. From the point-of-view of someone on the platform both you and the objects in the compartment are moving. Which is the right opinion? Of course, both are. The reason being that whether something is moving or stationary is an objective statement about reality, but one that depends on (or is relative to) the movement of the observer.

|

|

|

This kind of relativity, that depends on the movement of the person making the observations, is called Galilean relativity.

|

|

|

Another example of an objective scientific theory of relativity is Einstein's theory of special relativity, which is not a subjective theory about the nature of space and time.

|

|

|

Thus the disagreement in ethics may be due to its being relative. In general, this argument over-exaggerates the amount of agreement in so-called objective science. In science there are frequent arguments over the truth of a statement, which arise from one or both of the above factors.

|

|

|

Hence “the argument from relativity” is misnamed. It should be called “the argument from disagreement” since relativity is one way in which that disagreement could be explained.

|

|

|

Notwithstanding this conclusion that the argument from relativity is a fallacy, it still retains a powerful hold over the thinking of philosophers. This is illustrated by the following extract from J.L. Mackie's work Ethics.

|

|

The argument from relativity has as its premise the well-known variation in moral codes from one society to another and from one period to another, and also the differences in moral beliefs between different groups and classes within a complex community. Such variation is in itself merely a truth of descriptive morality, a fact of anthropology which entails neither first order nor second order ethical views. Yet it may indirectly support second order subjectivism: radical differences between first order moral judgements make it difficult to treat those judgements as apprehensions of objective truths. But it is not the mere occurrence of disagreements that tells against the objectivity of values. Disagreements on questions in history or biology or cosmology does not show that there are no objective issues in these fields for investigators to disagree about. But such scientific disagreement results from speculative inferences or explanatory hypotheses based on inadequate evidence, and it is hardly plausible to interpret moral disagreement in the same way. Disagreement about moral codes seems to reflect people's adherence to and participation in different ways of life. The causal connection seems to be mainly that way round: it is that people approve of monogamy because they participate in a monogamous way of life rather than that they participate in a monogamous way of life because they approve of monogamy.

.... In short, the argument from relativity has some force simply because the actual variations in the moral codes are more readily explained by the hypothesis that they reflect ways of life than by the hypothesis that they express perceptions, most of them seriously inadequate and badly distorted, of objective values. |

|

|

|

This passage merits some close observation.

|

|

| The argument from relativity has as its premise the well-known variation in moral codes from one society to another and from one period to another, and also the differences in moral beliefs between different groups and classes within a complex community. |

|

|

|

In this sentence Mackie begins by stating the premise of the argument, which can be simply summarised by saying that there have been disagreements about values. In this next sentence he states that the argument is a fallacy.

|

|

| Such variation is in itself merely a truth of descriptive morality, a fact of anthropology which entails neither first order nor second order ethical views. |

|

|

|

In other words from the fact that there is disagreement (a fact of “descriptive morality”) no value arises (no “first order.. ethical views”). It also does not entail anything about how values arise (no “second order ethical views”).

|

|

|

However, he goes on to state that the argument does support subjectivism

|

|

| Yet it may indirectly support second order subjectivism

|

|

|

|

A point that he repeats in his conclusion

|

|

| .... In short, the argument from relativity has some force simply because the actual variations in the moral codes are more readily explained by the hypothesis that they reflect ways of life than by the hypothesis that they express perceptions, most of them seriously inadequate and badly distorted, of objective values. |

|

|

|

The notion of “support” is vague. He acknowledges that the argument is a fallacy, but still wishes it to lend “force' to the conclusion that ethics is subjective. This seems to be like having your cake and eating it. His supporting argument assumes the theory that ethical values are derived from conditioning, which is equivalent to subjectivism.

|

|

| Disagreement about moral codes seems to reflect people's adherence to and participation in different ways of life. The causal connection seems to be mainly that way round: it is that people approve of monogamy because they participate in a monogamous way of life rather than that they participate in a monogamous way of life because they approve of monogamy. |

|

|

|

This is circular. Mackie is a subjectivist, so he does not acknowledge that objectivists can and do have adequate explanations for disagreements between people.

|

|

|

Christians believe in sin, and they believe that the bulk of humanity is in a state of sin. This means, disobedience to the moral commands of God. In confession a sinner acknowledges that he or she is wrong, but for the bulk of the time the sinner refuses to acknowledge his or her mistake, and builds a defence of it — a rationalisation. Now this is an example of a form of objectivism, and one that many nowadays might reject, but it serves to show that objectivist can as easily account for disagreements about questions of value as can subjectivists.

|

|

|

In conclusion, the argument from relativity is a fallacy.

|

|

III. Relativism |

|

Relativism is the view that ethical statements are genuinely relative to culture, society, situation and even the individual. Thus, what is right in one society may be wrong in another; what is right at one moment in time, may be wrong in another.

|

|

|

For example, in Shakespeare's play Titus Andronicus Shakespeare relates the life of a man (Titus) who at the beginning of the play commits an act of human sacrifice. This act is demanded by the “Gods” — in other words, is an act required by time honoured tradition. As the play evolves it is clear that Titus is a man of great moral worth. Although his action leads him and his family into misery, the blame for that lies not in his action as such but in society. It could be argued that Titus's act of human sacrifice was moral in the context he was living in, and would be immoral now.

|

|

|

Contemporary issues of disagreements in morality are even more controversial (because they are contemporary). For instance, in Arab societies it is permissible to have three wives and the position of women in society, regarding their status and right to property, is inferior to that of men. In Western societies the rule is monogamy and women have the right to own property. One way to resolve the tension between these systems of belief is through relativism: it is right in Arab society to have three wives, but wrong in Western society.

|

|

|

Relativism could be consistent with either objectivism or subjectivism. It is opposed to absolutism — the view that what is good and right applies in the same way to all people, in all situations regardless of time or culture.

|

|

|

Although relativism holds out interesting possibilities in terms of our understanding of ethics, moral philosophers have tended to shy away from it.

|

|

IV. Objectivism |

|

It is ironic that whilst subjectivists sometimes claim that the disagreement among people proves that morality is subjective, objectivist have a parallel argument that states that unless there is a belief in an objective moral reality then there will be a decay of morals. For example

|

|

| 1 | | There is no objective moral reality . |

| 2 | | Therefore, Everything is permitted . |

| 3 | | Therefore, No act of selfishness, however criminal, can be said to be wrong. |

|

|

|

It is claimed that there is an argument from subjectivism to immoralism.

|

|

|

In the past many thinkers have felt they needed to establish the existence of an objective moral reality in order to counter immorality. Plato believed that the subjectivist theories of the sophists were corrupting the young. If a moral reality does exist, then it will enable us to know what is good and right, and hence enable us to regard certain things and actions as bad and wrong. However, some C20th philosophers (for example, Mackie) maintain that subjectivism (second-order theory) is in fact compatible with any first-order theory. A subjectivist simply decides, on the strength of his feelings, what he believes is good and right. He may, it is claimed, believe in anything upon this basis. Anything that an objectivist could assert could be asserted on subjective grounds. This argument is generally regarded as valid.

|

|

|

However, in the past subjectivism has always been felt to be something that must be refuted, if immorality is to be shown for what it is. One reason for this may be the close association between ethical egoism (and immoralism) and subjectivism, and there may be good reasons for this association, which fall short of actual logical entailment. This is a matter of psychology more than logic.

|

|

|

It is natural to have self-centred feelings, and a subjectivist could never say that a person who did act selfishly was wrong as a matter of fact, though he could say he was wrong as a matter of feeling. The terms wrong and right (here in the sense of a factual truth) involve the concept of a reality that makes our judgements wrong and right. However, a subjectivist could reply to a selfish-minded person on the basis of his feelings — that he feels selfishness is wrong.

|

|

|

An objectivist can reply to an ethical egoist by saying that the egoist is wrong as a matter of fact. Furthermore, the egoists error will be followed by sanctions that demonstrate that he is wrong.

|

|

|

People who believe in objective moral judgements tend to believe that immorality (that is disobedience to an objective moral precept) is punished. Such punishment is not necessarily (or generally) thought to occur in life itself. The eastern law of karma may fit into this idea. Most religions employ a concept of judgement.

|

|

|

Nonetheless is theoretically possible that a moral obligation may be objective and yet not subject to any sanction.

|

|

V. Amoralism and egoism |

|

Amoralism is the claim that there is no answer to the question, “Why should I do anything?” This position is often confused with ethical egoism. It may also be uninteresting — people do have motives for action, which is a point that Bernard Williams makes in this extract from his work Morality.

|

|

Bernard Williams is concerned with the question of whether a person who claims to be totally unaffected by morality poses some kind of challenge to those who do believe in morality.

Why should I do anything? ... Why is there anything that I should, ought to do?

The man who asks [this question] ... has been regarded by many moralists as providing a real challenge to moral reasoning.

... does he [the amoralist] care for anybody? Is there anybody whose sufferings or distress would affect him? If we say 'no' to this, it looks as though we have produced a psychopath. If he is a psychopath, the idea of arguing him into morality is surely idiotic, but the fact that it is idiotic has equally no tendency to undermine the basis of morality or of rationality. The activity of justifying morality must surely get any point it has from the existence of an alternative — there being something to justify it against.

... This is the vital point: this man is capable of thinking in terms of others' interests, and his failure to be a moral agent lies (partly) in the fact that he is only intermittently and capriciously disposed to do so. But there is no bottomless gulf between this state and the basic dispositions of morality. |

|

|

|

A more serious challenge comes from the question whether there are any ethical reasons for action as distinct from egoistical ones, which brings us to ethical egoism.

|

|

|

Ethical egoism is the claim that there is no moral obligation upon a person to do anything other than what he sees as being conducive to his own advantage. The ethical egoist is regarded as positing a serious challenge to moral thinkers — a challenge to prove to an egoist that obligations and so forth do exist.

|

|

|

We have already seen that an objectivist can reply to the ethical egoist. The egoist is wrong as a matter of fact about the world he lives in, and, furthermore, most objectivists would claim that selfish acts that are immoral will be followed by sanctions.

|

|

|

The challenge, therefore, is really posed to the subjectivist.

|

|

|

Subjectivists have two answers to this challenge: (1) the theory of rational self-interest; (2) a biological-evolutionary theory about the origin of conscience. Both theories are related.

|

|

|

The theory of rational self-interest maintains that a system of morality serves the self-interests of most people. For example, this is often used in political theory to explain why the state arises and why we should obey the commands of the state. People are better off in a state than outside it. Here is one version of that argument from Locke's Second Treatise of Human Government.

|

|

If man in the state of nature be so free as has been said, if he be absolute lord of his own person and possessions, equal to the greatest and subject to nobody, why will he part with his freedom, this empire, and subject himself to the dominion and control of any other power? To which it is obvious to answer, that though in the state of nature he hath such a right, yet the enjoyment of it is very uncertain and constantly exposed to the invasion of others; for all being kings as much as he, every man his equal, and the greater part no strict observers of equity and justice, the enjoyment of the property he has in this state is very unsafe, every insecure. This make shim willing to quit this condition which, however, free, is full of fears and continual dangers; and it is not without reason that he seeks out and is willing to join in society with others who are already united, or have a mind to unite for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates, which I call by the general name — property.

[It might be more appropriate to quote from Hobbes' Leviathan since Hobbes was a materialist and did not believe that rights existed except by agreement based on rational self-interest and Locke believed that rights did exist in a “state of nature”, but that they could not be enforced. However, Locke's version here is clearly, and hence serves the purpose of the exposition better. Those interested in Hobbes' version should read The Leviathan Part I, Chapters 13 and 14.] |

|

|

|

Mackie calls such arguments “prudential reasons” for acting ethically. In other words, as a subjectivist, Mackie seeks to base morality on rational self-interest. However, he acknowledges that this is not sufficient.

|

|

| But this does not completely resolve the tension. It leaves unanswered the question 'Why should I not at the same time profit from the moral system but evade it? Why should I not encourage others to be moral and take advantage of the fact that they are, but myself avoid fulfilling moral requirements if I can in so far as they go beyond rational egoism and conflict with it?' It is not an adequate answer to this question to point out that one isnot likely to be able to get away with such evasions for long. There will be at least some occasions when one can do so with impunity and even without detection. Then why not? To this no complete answer of the kind that is wanted can be given. In the choice of actions moral reasons and prudential ones will not always coincide. [J.L. Mackie: Ethics — Elements of Practical Morality.] |

|

|

|

This is where the subjectivist's second argument comes in. They claim that as a matter of evolutionary fact people have evolved moral sentiments. They are born into societies that condition them into having moral feelings. They acquire as a result a conscience. It does not matter that this conscience is social in origin, and has no relationship to an objective moral reality; it may be a psychological force, but it is real enough. Actions that contradict one's conscience hurt just as much as if a God were really there to punish one for them. Hence, actions in accordance with conscience are still prudential. It is still in one's self-interest not to go against one's own conscience.

|

|

| If someone, from whatever causes, has at least fairly strong moral tendencies, the prudential course, for him, will almost certain coincide with what he sees as the moral one, simply because he will have to live with his conscience. [J.L. Mackie: Ethics — Elements of Practical Morality.] |

|

|

|

This would be further supported by other observations on the evolution of human nature and society. As an evolutionary fact we have developed a society. Survival of the species depends on the development of certain sentiments that are moral as opposed to egocentric. When individuals develop in society with over-strong egocentric interests, so that they are led into aberrant acts, society as a whole organises against them and they are hunted down, arrested and punished by the criminal justice system. The education system and other systems of social control serve to inculcate ethical feelings, so that by time puberty is over only a few individuals are not sufficiently conditioned to lead relatively productive lives which involve only rare infringement of the moral rules. Those individuals that have passed through the net are quite easily identified, and dealt with by the criminal justice system. There is no objective reason why their actions are wrong, but the majority feels that their actions are wrong, and as a matter of fact, treats them accordingly.

|

|

|

However, this theory of rational self-interest, even when coupled to this biological-evolutionary theory, is unstable, since it is theoretically possible that a drug could be invented that would put to sleep the conscience, and that individuals could take this drug just whenever they seriously wanted to do something that was in their self-interest but contrary to the interest of the community or other individuals.

|

|

VI. Universal tolerance |

|

The argument from the claim that there must be universal tolerance to subjectivism is also a fallacy. The claim to the need for universal tolerance is probably untenable — Does one tolerate the intolerant? Belief in tolerance is consistent with either an objectivist or a subjectivist meta-ethics.

|

|

VII. Hedonism |

|

However, the issue of what motivates a person cannot be separated from ethical issues. We acknowledge that the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain are motives for action. If there are ethical values other than those of pleasure and pain, then the pursuit of these will constitute additional motives for action.

|

|

|

Hedonism is the view that the only things that are good are pleasures and pain. Since what is good provides a motive for action, Hedonism asserts that the only things that are true motives for action are pleasure and the avoidance of pain. Epicureanism is the claim that in order to maximise a life of pleasure, a rational man will not pursue pleasure to excess at any one given moment — since excessive indulgence in pleasure leads to bad health, which is a form of pain. The epicurean may choose between pleasures, and discriminate some as inherently better than others; however, it he does so, it may be that he accepts some other form of value in addition to that of pleasure.

|

|

|

Compare two lives, both of which are equally pleasurable (assuming that it is possible to measure pleasure). One is the life of a pig, the other is the life of a man like Socrates. Which, if either, is the better life? The Hedonist must logically view the choice with indifference. Neither is better since the pleasure involved in both is the same. If one decides in favour of the man, then there must be some other form of value in addition to pleasure.

|

|

|

Are there pleasures, for example, sadism, that are inherently bad? The Hedonist must say that no pleasures, in themselves, are bad. Certain action may be viewed as bad because they lead to bad consequences. Sadism is bad for this reason, but not bad because of the pleasure derived from sadistic acts. If this argument is rejected, then Hedonism must be false. For then, the class of pleasurable things would not be identical to the class of good things.

|

|

|

Hedonism is associated with ethical egoism as follows. If the only true motives for action are pleasure and the avoidance of pain, it would be rational to argue that since there are no objective values the only things I need act upon are what gives me pleasure, and I will avoid what gives me pain. Above all, there is no reason why I should consider the pains and pleasures, or well-being at all, of other people. There is no reason why I should not regard all other people as merely means to the gratification of my own desires.

|

|

|

However, hedonism is also consistent with the idea that all people's pleasures and pains count. This gives rise to the philosophy of utilitarianism, which is considered elsewhere.

|

|

VIII. Fact/value gap |

|

Subjectivists often argue that in the case of actual moral disputes, participants argue not as to the validity of fundamental ethical principles, but as to the validity of certain facts that are held to impinge upon the issue. For example, abortion. The issues of whether to shorten the period of time in which a woman can have a legal abortion may devolve upon the factual issue of when the foetus is recognisably human.

|

|

|

The fact/value gap was advanced initially by Hume in his Treatise as follows.

|

|

| I cannot forbear adding to these reasonings an observation, which may, perhaps be found of some importance. In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remark'd, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surpriz'd to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptive; but is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relations or affirmation, 'tis necessary that it shou'd be observ'd and explain'd; and at the same time that a reason should be given, for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it. But as authors do not commonly use this precaution, I shall presume to recommend it to the readers; and am persuaded, that this small attention wou'd subvert all the vulgar systems of morality, and let us see, that the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceiv'd by reason. |

|

|

|

The fact/value gap simply asserts that one cannot argue from a factual statement to an ethical statement, without the use of some purely ethical premise. Arguments which appear to do so are either fallacies, or tacitly assume an ethical first premise.

|

|

|

There have been some spurious attempts to refute the fact/value gap. One of these is by John Searle, who argues that the following sequence of statements takes one from a fact to a value.

|

|

| (1) | | Jones uttered the words 'I hereby promise to pay you, Smith, five dollars.' |

| (2) | | Jones promised to pay Smith five dollars. |

| (3) | | Jones placed himself under (undertook) an obligation to pay Smith five dollars. |

| (4) | | Jones is under an obligation to pay Smith give dollars. |

| (5) | | Jones ought to pay Smith five dollars. |

|

|

|

This is a piece of sophism. We can see this firstly by the fact that the utterance of the words, “I hereby promise to pay you five dollars”, does not, of itself, entail an obligation. For example, the promise must be made in the context that is free from duress or for any need for deception. With out this information the inference from (1) to (3) is invalid. More importantly, an ethical premise is needed, “People should keep their promises”, for without this no further practical application expressive of a value can follow. Searle has diluted the inference from what is a fact to a statement of value, and hence made the transition from the one to the other almost imperceptible. In fact, the gap is breached between statements (3) and (4), since (3) is still a factual statement, whereas (4) is a statement of value. To pursue this matter in any further detail would be tedious.

|

|

|

A more serious objection to the fact/value gap is that it breaches its own fact/value gap.

|

|

|

Fact: There is a distinction between factual and value statements.

|

|

|

Value: We ought not to argue from fact to value.

|

|

|

Hume is arguing to the effect that hitherto all such fact to value arguments have been fallacious. Hume offers no a priori reason for supposing that the fact/value gap is correct. Thus, the fact/value gap can be disputed.

|

|

|

Furthermore, as should be apparent from the preceding discussion, objectivists, who have most to lose by accepting the fact/value gap, tend not conceive of a distinction between a fact and a value. The most famous example of such an objectivist would be Plato. Plato does not acknowledge a distinction between fact and value. When he describes the Form of the Good as the highest reality, he equates what is morally perfect with what is ultimately real. It may be questioned whether this is intelligible, but clearly Hume's critical point comes from within the subjectivist camp, and objectivists have a wholly different conception of how values arise and one that does not preclude the possibility that a fact is a value.

|

|