|

Social mobility |

Early studies of social mobility |

|

It is believed that social mobility in industrial societies is greater than in pre-industrial societies. That is, people can progress from one social stratum to another with more ease in modern society than in agricultural society. The system of social stratification has become more open; status is more achieved rather than ascribed.

|

|

|

It is usual to study social mobility in terms of occupational mobility. David Glass et al conducted a study of intergenerational mobility in 1949, using occupational categories as follows:

|

|

| 1 | | Professional and high administrative |

| 2 | | Managerial and executive |

| 3 | | Inspectional, supervisory and other non-manual (higher grade) |

| 4 | | Inspectional, supervisory and other non-manual (lower grade) |

| 5 | | Skilled manual and routine grades of non-manual |

| 6 | | Semi-skilled manual |

| 7 | | Unskilled manual |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The figures suggest that only two-thirds of the men interviewed were in the same social category as their fathers. However, the degree of movement is not great — most movement is either into the category just above or just below that of a man's father. For example, only 0.5% of those in the highest occupational category had fathers who were unskilled manual labourers.

|

|

|

Similar conclusions were reached by the Oxford study of mobility conducted in 1972. This study categorised occupations in terms of their economic rewards rather than their social prestige. This study indicated that there was more long-range mobility. For example, 2.4% of the members of their highest occupational category (professionals, etc) had fathers who were members of the lowest occupational category (semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers). However, once the effect of deindustrialisation is taken into account, there may not be greater social mobility in modern Britain than there was in Edwardian Britain. This point is analysed by Kellner, using the concept of relative mobility. He divides the working population into three bands, working, intermediate and service. He analyses life chances of those born during the period 1908-17 and compares them with life-chances of those born during the period 1938-47. Whilst the proportion of people employed in the service category has increased from 13% for the first group to 25% for the second group, the relative chances of moving from one group to another have remained the same. If this is true, then there has been no change in social mobility in Britain over the C20th.

|

|

|

Another major criticism of these studies is that they exclude women from the analysis. However, Goldthorpe and Payne have replied by arguing that the non-inclusion of women in the study has not affected the overall conclusions of the survey — in other words, women follow the same pattern as men. This raises the issue of gender and social class.

|

|

Goldthorpe's mobility survey 1980 |

|

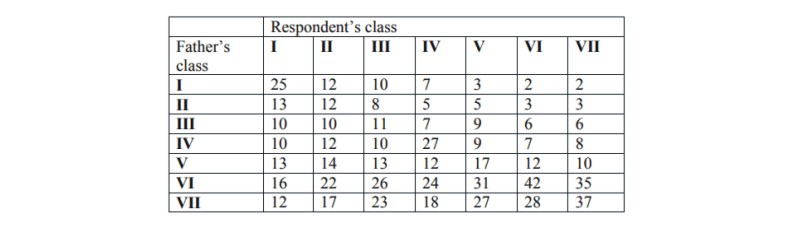

The following table gives the results of Goldthrope's mobility survey. [Goldthorpe et al: Social Mobility and Class Structure in Modern Britain.] The figures show percentages. For example, 25% of people in class I had fathers who were in class I.

|

|

|

|

Source: Saunders, Social Class and Stratification

|

|

|

This mobility study is based on the following definition of occupational class

|

|

Class I

Higher-level professionals, administrators, technicians, managers and supervisors of non-manual employees

Class II

Lower-grade professionals, technicians, managers and supervisors of non-manual employees

Class III

Clerical and social service workers in non-manual occupations

Class IV

Small business people

Class V

Blue collar elite — lower-grade technicians, foremen, and so on

Class VI

Skilled manual workers

Class VII

Semi- and unskilled manual workers

|

|

|

|

Summary of the findings

|

|

|

From the period of the end of the Second World War to circa 1972, men of all classes and origins have become more likely to move into professional, administrative and managerial positions — that is to have an occupation within the service industry. There has been a growth of the “service class” and a contraction of the “working class”. Upward mobility into the “service class” has increased; downward mobility from the “service class” into the “working class” has decreased; the “working class” is less stable intergenerationally; the “service class” is more stable intergenerationally.

|

|

|

1972 as a watershed year

|

|

|

1972 is taken to be a watershed year. In the years immediately after 1972 the British economy experienced a supply side shock — the Arab-Israeli war of 1974 (the Yon Kippur War) initiated the first oil crisis. The fourfold increase in oil prices that resulted from the formation of OPEC led to a worldwide depression. In this context the structural weaknesses of the British economy were exposed and Britain experienced a period of stagflation — high inflation and high unemployment. Subsequently, the British economy has restructured; as a proportion of the total output, manufacturing has declined and the service sector has increased.

|

|

|

However, Goldthorpe maintains that the findings from the 1972 survey extend to into the 80s and that the conclusion that the “service class” has stabilized and the “working-class” has become less stable would still apply.

|

|

|

An original survey was conducted in 1972, and repeated in 1980. Goldthorpe concludes that these findings still apply despite the upheavals in the British economy during the period from 1972 to 1980.

|

|

| The main outcome of our comparison of intergenerational class mobility tables for 1972 and 1983 is then that, despite the transition from one economic area to another which occurred between these dates, a very large measure of continuity can be observed.

|

|

|

|

Goldthorpe's “refutation” of the Marxist “labour process” thesis

|

|

|

Goldthorpe believes that the findings refute the “the Marxist 'labour process' theory of class structural change which claims a necessary 'degrading' of work and a progressive proletarianization of the work-force under capitalism”.

|

|

| It is professional, administrative, and managerial occupations that are in expansion, while the greatest decline is found in manual wage labour.

|

|

|

|

There is an “obvious” reply to this claim, which is that the service sector jobs into which the manual classes have moved have themselves been proletarianised.

|

|

| As a last line of defence for the 'degrading' thesis, it may be maintained that some sizeable part of the expansion of administrative and mangerial positions in particular should be recognized as more apparent than real. This is so because many of these positions either have been themselves degraded into essentially subordinate ones, involving only routine tasks, or have been created by an upgrading of such subordinate positions of no more than nominal or cosmetic kind. |

|

|

| His reply to this objection is simply that “no systematic empirical support for such arguments has so far been brought forward”.

|

|

|

Critique of this “refutation”

|

|

|

Marx wrote within the context of a C19th industrial society. The proletariat as a class was broadly identical to the class of people employed in manual physical labour. Employment in these industries was alienating. Employees worked in boring and repetitive jobs with no control of the conditions under which they were employed.

|

|

|

Since the C19th the structure of the economies of developed countries has changed and the proportion of the work force employed in manual physical labour has significantly declined.

|

|

|

Thus, we are forced to examine more closely the definition of “proletariat”. It is clear from the writings of Marx, and independent reflection, that the correct definition is in terms of “class-situation”, as these extracts from The Communist Manifesto show:

|

|

| 1 | | By bourgeoisie is meant the class of modern Capitalists, owners of the means of social production and employers of wage labour. By proletariat, the class of modern wage-labourers who, having no means of production of their own, are reduced to selling their labour power in order to live. (Note by Engels.) |

| 2 | | In proportion as the bourgeoisie, i.e., capital, is developed, in the same proportion is the proletariat, the modern working class, developed — a class of labourers, who live only so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labour increases capital. These labourers, who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are consequently exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations of the market. |

|

|

|

This extract illustrates the “labour process” thesis:

|

|

| Owing to the extensive use of machinery and to division of labour, the work of the proletarians has lost all individual character, and consequently, all charm for the workman. He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him. Hence, the cost of production of a workman is restricted, almost entirely, to the means of subsistence that he requires for his maintenance, and for the propagation of his race. But the price of a commodity, and therefore also of labour, is equal to its cost of production. In proportion, therefore, as the repulsiveness of the work increases, the wage decreases. |

|

|

|

Thus, the question we have to examine in dealing with class in modern Britain or elsewhere is whether you are employed in the service industry or manufacturing has your class situation changed? Thus, one relevant question would be: do the majority of white-collar workers in, for example, banking and selling, have the power not to work? To illustrate the significance of this question consider this definition of the dividing line between the working and middle classes in Vanneman and Cannon's The American Perception of Class:

|

|

| Our own classification ... limits the middle class to the self-employed (that is, the “old” middle class of storekeepers and independent farmers) and professionals and managers (the “new” middle class whose members share the responsibilities of managing the lives of other workers). Additional workers who have sometimes been counted as middle class (e.g., white-collar clerical workers, technicians, salespersons, and even the more affluent craftsworkers) do not attain the control over other workers or even over their own lives that sets the middle class apart from Marx's proletariat.

|

|

|

|

On the basis of this definition, these authors conclude that the size of the American working class has expanded from 61% in 1900 to 70% in 1980. The conclusion of this could be that you can be in the working class (that is, proletariat) even if you have a white-collar job. Thus it can be argued that Goldthrope confuses a change in occupational structure with a change in class.

|

|

|

This confusion is illustrated by the use of “service class” in the above summary. It is usual to reserve this term for a very small number of elite professionals and directors who through their service to the upper class are paid such high salaries that they can accumulate sufficient wealth in order to enter the upper classes. The upper classes require such a service class who translate their economic power into reality. Below them are the middle class managers and lower-grade professionals; below these come the manual (“blue collar”) and service-sector (“white collar”) employees who constitute the working class. To be in the service class you have to have the equivalent of directorial power (over a large company) and be paid accordingly.

|

|

|

In other words, Goldthorpe's survey merely charts the effects on occupation of the progression of the British economy through deinstrialisation and the consequent growth of the service sector.

|

|

|

Offset against this there is the general rise of affluence and the spreading of property ownership. These comprise an “embourgeoisement” of the working class, and it is a debatable point whether this embourgeoisement has changed the class-situation of the working class and reduced the effects of alienation in employment.

|

|

|

Unemployment

|

|

|

At the time when Goldthorpe was writing there was a high level of unemployment in Britain. Goldthorpe sees unemployment as the biggest threat to the opportunities of working class people.

|

|

| For men of working- and intermediate-class origins in particular, the pattern of their possible mobility experience has been significantly reshaped over recent years as unemployment, rather than occupational immobility or decline, has come to represent the alternative pole to gaining entry to a high-level class position. |

|

|

|

From one prospective, the proletariat can be broadly divided into three occupational subclasses: the manual and non-manual (service) occupational sub-classes and in addition to this, the unemployed. The point is that a man born into the manual working class may migrate, due to economic pressure, either into the non-manual working class, or into the unemployed working class. Additionally, workers in the service sector have greater job security than workers in manual sector. This is for economic reasons. The trade cycle (the cycle of booms and recessions in the economy) creates greater instability for employees in the manual sector than for employees in the service sector. It is probably for this reason that the service sector proletariat occupies an occupational status above that of the manual sector.

|

|

Peter Sauders: Social Class and Stratification |

|

Peter Saunders, a modern functionalist associated with the New Right, draws the following conclusions from Goldthrope's study

|

|

|

Trends in social mobility

|

|

|

Saunders distinguishes between two kinds of mobility: (1) intra-generational mobility — movement within one's lifetime — for example, when the bank clerk ends up as a managing director; (2) inter-generational mobility — for example, when the child of a bank-clerk ends up as a managing director.

|

|

|

Movement may be upward or downward.

|

|

|

Saunders maintains the thesis that there is (1) increased upward mobility; (2) that “upward social mobility is more common than movement downwards.” The cause of these developments is deindustrialisation, which is “a shift in employment from industry to services”.

|

|

|

Measuring social mobility

|

|

|

Saunders acknowledges that “marginal changes” in position may not constitute real social mobility. He acknowledges that a few more GCESs and a white-collar job do not necessarily constitute upward movement. He admits that (1) “large-scale upward movement across very narrow ranges ... may be virtually insignificant as regards people's life-chances, life-styles and self-conceptions.” (2) That movement upwards in one-dimension (for example, change in social status) does not equal movement upwards in another dimension (for example, change in income). (3) That we must be aware of “lumpy” movements — for example, a filing clerk leaving work, having children, and returning to a different employment.

|

|

|

Making comparisons

|

|

|

Social status is relative to culture — for example, manual work was more highly regarded in the Soviet Union than it is in Britain. Additionally, as upward mobility is more common than downward mobility focusing on upward mobility distorts issues. There are very few directors that end up sweeping the streets. Analysis that focuses on downward mobility would conclude that “the system is remarkably static and closed.”

|

|

|

Social inequalities and Natural inequalities

|

|

|

Saunders argues that high mobility does not mean that we live in a meritocracy — that is, high mobility does not necessarily arise from a fair society. “It may be that the members and children of the upper strata have maintained their position as a result of success in open competition with members of other classes.” He has sympathy for Durkheim's view “that industrial societies would never operate harmoniously until social inequalities came to reflect the distribution of natural inequalities.” He supports the view that genetic inheritance is the cause of “a relative lack of movement across wide spans in the occupational society.”

|

|

|

Social mobility and contemporary Britain

|

|

|

Saunders discusses Goldthorpe's Oxford Study in the early 1970s of social mobility. Goldthorpe studied 10,000 men in England and Wales between the ages of 20 and 64. He concluded from this that “inter-generational opportunities have expanded but intra-generational opportunities have contracted.” This is because wider educational opportunities have increases working-class upward mobility.

|

|

|

Saunders discusses the closure thesis of Tom Bottomore and Ralph Milband “that social mobility is always limited to short range and that top positions are virtually immune to its effects.” However, Saudners claims that Goldthorpe's data disproves this — only one quarter of men in Class 1 were born into it. He discusses and rejects the buffer zone thesis that most movement is limited to skilled manual and clerical positions. Goldthorpe's data shows 7% of sons of working-class fathers are now in Class 1, and 15% of sons of Class II and III fathers are now in the manual working-class.

|

|

|

Thus, all-in-all, Sauders believes that Britain is “a fairly open society”. He claims it is “fatuous to conclude that Britain is a closed society in which a dominant class perpetuates itself while excluding others from its privileges.”

|

|

|

How open is the British Class System?

|

|

|

Saunders agrees with Bauer that the idea that Britain operates a “restrictive and divisive class system, almost a caste system” is a myth. He discusses and criticises Goldthorpe's concept of relative mobility — that the relative positions in society have not changed although in “absolute” terms they have. He counters this with a general defence of capitalism — capitalism generally improves people's living standards. It must be accepted that “capitalism always entails inequality between top and bottom.” He maintains that Britain is a meritocracy where “talents are unevenly distributed among people, that the most talented tend to rise towards the higher social positions, and that they tend to pass on some of their genetic advantages to some of their offspring.” This is a general defence of inequality in Britain on the grounds that it is created by competition amongst individuals and is necessary to the economic prosperity of all.

|

|

|

The changing class system in Britain

|

|

|

Saunders is opposed to Marx, who advanced the thesis that as time progresses the class system becomes more polarised. His counter-thesis is that the class structure becomes increasingly fragmented, complex and differentiated.

|

|

|

However, he admits that Goldthorpe's categories of class omits (1) the capitalist class and (2) the underclass — also called the lumpenproletariat.

|

|

|

Saunders does not consider the distribution of wealth and the inheritance of wealth at all in any part of his argument. He also omits any discussion of cultural capital.

|

|

|

Saunders notes that less than 25% of the largest 250 companies are run by directors that own as much as 5% of the shares. He does acknowledge that there is a very small business elite, comprising a few thousand individuals that run Britain's major companies. He claims that the ownership of companies has been diffused, and control has passed to a business elite. He cites the following statistics for share ownership.

|

|

| 1958 | | >7% own shares |

| 1979 | | 4.5% own shares |

| 1987 | | 19% own shares, though approximately 10% own less than £1,000 in share assets

|

| 1963 | | Through the development of pension funds and unit trusts, 18% have some form of share ownership

|

| 1975 | | Through pension funds and unit trusts 38% have share ownership. |

|

|

|

Thus, he claims that indirect ownership through participation in a pension fund has increased. He claims that workers in fact own the bulk of the capital of the country. He also claims that ownership and control are not separated.

|

|

|

Saunders considers the “moving column thesis” — that there has been a general change in class structure owing to deindustrialisation — thus, people are upwardly mobile in terms of occupational class because generally people are changing from manual to clerical work. He accepts that there has been a general increase in affluence. He acknowledges that such developments do not necessarily improve the class situation or constitute the evolution of a different consciousness.

|

|

|

He also adopts Lockwood's distinctions between three types of manual worker.

|

|

| 1 | | The traditional proletarian — that is, coal miners, dockers, shipbuiders; this kind of worker adopts and 'us' and 'them' type of class-consciousness, and such workers possess a strong sense of class solidarity.

|

| 2 | | The traditional differentiated worker — workers in service industries, agriculture and family firms. Such people develop a class consciousness based on being “different people ... finely graded along a status hierarchy.” |

| 3 | | Privatised workers — they have no sense of class identity and “repetitive and alienative work tasks lead them to focus their life outside of work as their major interest and source of identity.” They typically work in engineering, chemicals and car assembly. |

|

|

|

Saunders does not accept that privatised workers have undergone embourgeoisement.

|

|