|

Tom Bottomore: Classes in Modern Britain |

The Nature of Social Class |

|

Bottomore defines social stratification to be “any hierarchical ordering of social groups or strata in a society.” The older forms of social stratification are based on slavery, caste or estate; newer forms are based on social class (that is, economic class) or status group.

|

|

|

He takes the view that social stratification does not rest on biological difference. He also quotes T.H. Marshall (1950) who wrote, “the institution of class teaches the members of a society to notice some differences and to ignore others when arranging persons in order of social merit.” Class is maintained through inheritance: “... inequalities of incomes depends very largely upon the unequal distribution of property through inheritance, and not primarily upon the differences in earned income..” Class differences do not arise out of differences in abilities — we do not live in a meritocracy: “... intellectual ability ... is by no means always rewarded with high income or high social status, nor lack of ability with the opposite.”

|

|

|

Modern social classes are based on economic differences between individuals in relation to the labour market. As a result there are intermediate positions between the bourgeoisie and the working class.

|

|

|

There is some mobility between the classes, but the acquisition of wealth is not, according to Bottomore, sufficient to raise an individual into the bourgeoisie.

|

|

Classes in Modern Britain |

|

Bottomore sites some historical examples of authors who agree that there is a distinction between proletariat and bourgeoisie in Britain. For example, Disraeli refers to the emergence of “two nations” in his novel Sybil (1845). Matthew Arnold also remarked that there was a “religion of inequality” which was based around the notion of the “gentleman ideal”.

|

|

|

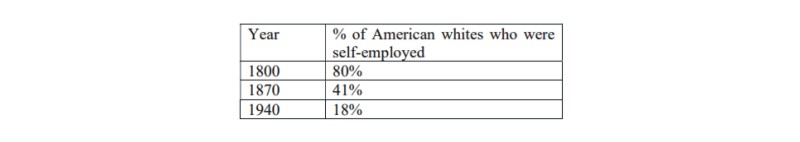

Bottomore draws on various sources to support his thesis that in Britain today being a landowner, financier or merchant enjoys a higher status than being an industrialist. He believes that this is linked to the decline of Britain as an industrial nation. He contrasts the ownership of property in Britain, and its class divisions, with the situation in America. In the period after the American war of independence 80% of the working population (which, however, excludes slaves) owned the means of production with which they worked. It was a society of small farmers, small traders and small businessmen. However, this structure has altered as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

Thus, in America there have been increasing distinctions of wealth over time, with the appearance of class divisions, and the establishment of exclusive boarding schools and country clubs. Workers have also rganized themselves into trade unions.

|

|

|

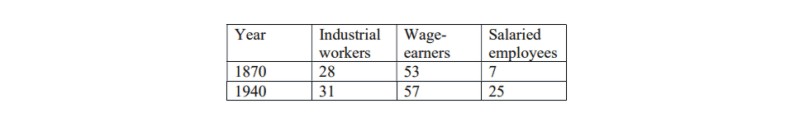

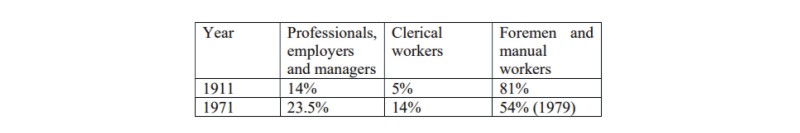

However, the Americans continue to believe that they are a nation of “small capitalists” (quoting the words of C.Wright Mills). The reason why this belief persists is because the decline of self-employment has not resulted in an increase of industrial workers as a percentage of the workforce. What has happened is that white-collar, “middle-class”, occupations have increased. The statistics would appear to be as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

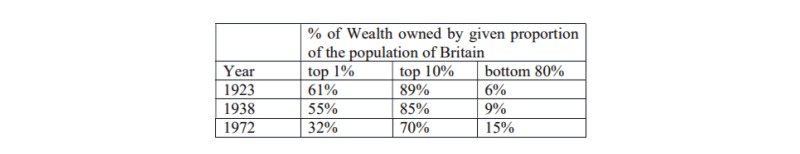

Returning to a discussion of the British class system, he reminds us of Charles Booth's survey of London (1887-91) that showed that 30% of the population of London was living in poverty. Rowntree's 1901 survey of London also showed 30% of the population was in poverty. In 1914 1% of the population owned 68% of all private property and earned 29% of national income. The statistics are as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

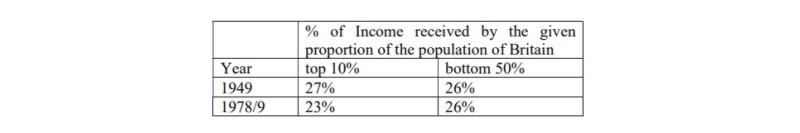

In 1938 10% of the population received 50% of national income. The distribution of income was as follows

|

|

|

|

|

He maintains that since 1979 there has been an increase in uneven distributions of wealth. He remarks that this pattern of ownership of wealth and distribution of income is generally the same for other countries.

|

|

|

In the 1970s public expenditure was around 40-50% of GDP. There was a period of “welfare capitalism” in which the aim was to maintain full employment and develop the national health services. The occupational class of domestic servants virtually disappeared. The development of social services in part served to mitigate the ills of social inequalities. An example of a social policy creating greater opportunities for all was the Education Act of 1944.

|

|

|

However, there has been a change in the structure of poverty. Before the Second World War all the working classes were in poverty. Subsequently, poverty was confined to particular isolated groups — to old people dependent on state pensions, to workers in certain occupations or regions, and to low-paid workers, ethnic groups, immigrant workers and the unemployed. These groups have not been able to organise themselves into a single coherent social movement.

|

|

|

He maintains that social mobility is confined solely to occupational mobility and is caused by the expansion of white-collar and professional occupations. This in turn has been brought about by (1) the expansion of the economy and (2) deindustrialisation. In any case, he maintains that a person's occupational class tends to follow class divisions based on wealth — that is, people who inherit more wealth tend to hold occupations with higher status. He discusses the relative mobilities in the USA and Eastern European countries. In the USA in modern times there has not been greater mobility into the elite or across the manual/non-manual labour boundary. He quotes research by Heath to support his view that the USA is not an exception to the rule about class structure. However, in Eastern Europe there have been higher rates of inflow into the elite and white-collar occupations. Modern industrial societies exhibit more mobility than the societies they have replaced.

|

|

|

He quotes the study by Routh (1980) on occupational class in Britain:

|

|

|

|

|

There has been a general shit from manual to white-collar work.

|

|

|

He appears to agree with the view that the middle class cannot be regarded as a single homogenous group and that there are many gradations of social status within this group. It merges with the working class at one end and with the elite at the other end.

|

|

|

He remarks on the different ways in which class position can be defined: (1) through the work situation, (2) through the market situation; (3) in terms of status position; (4) in terms of the possession or non-possession of property.

|

|

|

He discusses the thesis of the proletarianisation of the middle classes — how middle class occupations have become like working class occupations. He supports Braverman's thesis that clerical labour has been proletarianised as a result of the deskilling of clerical tasks. He notes Poulantzas's reply that people in clerical jobs do not have the ideology of a working-class person.

|

|

|

He observes the theory that a new elite has emerged which fuses the service class with the wealth owning class based on education criteria. However, he rejects this thesis. He also takes the view that the middle classes support and buttress the capitalist classes at the expense of the working class.

|

|

Commentary |

|

The description of the class structure of Britain depends on how that class structure is classified. Broadly, class can be defined in terms of occupation, income or wealth. Of these income is the least reliable basis for a classification, since you could derive the same income either from your occupation, or from your wealth (that is, from investments), but the implications would be very different for the kind of life-style and social status you have.

|

|

|

Whilst neither income nor wealth is evenly distributed in Britain (or other industrial/post-industrial societies) income is more evenly distributed than wealth. Also, mobility in terms of occupation is much greater than mobility in terms of wealth. Thus, depending on how you define class, your interpretation of the “fairness” of British society is affected. Your choice of definition may reflect your political and social bias.

|

|

|

There is also the question of how to define the working and middle classes. One approach is to equate the working class with manual employment (using a classification based on occupation); another approach is to equate the working class with their economic position — that is, whether you own or do not own the means of production (using a classification based on wealth). The second definition is derived from Marx. The second definition would encompass within the proletariat white-collar clerical jobs, so the second definition regards the proportion of the population who are working-class as relatively static, and the changes in occupational group, from manual to non-manual jobs, is a movement within the working class.

|

|

|

The middle classes can be defined according to occupation (clerical, non-manual, professional, managerial occupations) or according to wealth (ownership of the means of production.) The second approach, which is not actually adopted by Bottomore here, is illustrated from this quotation regarding the dividing line between the working and middle classes in Vanneman and Cannon's The American Perception of Class:

|

|

| Our own classification ... limits the middle class to the self-employed (that is, the “old” middle class of storekeepers and independent farmers) and professionals and managers (the “new” middle class whose members share the responsibilities of managing the lives of other workers). Additional workers who have sometimes been counted as middle class (e.g., white-collar clerical workers, technicians, salespersons, and even the more affluent craftsworkers) do not attain the control over other workers or even over their own lives that sets the middle class apart from Marx's proletariat. |

|

|

|

According to the occupational definition, the middle classes subsume all professional and directorial status groups. To be sure it is a very heterogeneous group and there is a great deal of mobility in it, and hence, no sharp distinction exists nowadays between the working and middle-classes and there is no distinct elite.

|

|

|

The definition in terms of wealth (that is, economic situation), regards the distinct middle-class as a small class, with non-manual, white collar workers belonging not to it, but to the working-class. This definition based on wealth exposes the existence of an upper élite of approximately 10,000 people, who, by virtue of their ownership of the greater proportion of the wealth of Britain, in fact are the ruling élite. Between the middle-class and the elite is a service class — individuals drawn from the middle or lower classes who by possession of skills unique to the survival of the élite are allowed to earn salaries that make it possible for them to accumulate wealth and enter the élite.

|

|

|

Thus, according to what your definitions of class are based on, you will have very different interpretations of the class structure of Britain and its relative “fairness”.

|

|

|

The debate over the fairness of the social structure will continue. Many will agree that Britain does have a class structure and some will regard much of the evidence of mobility as a reflection of changes in the structure of the economy, for example, owing to deindustrialisation, rather than the structure of society. However, these positions do not prove that the existence of the class structure is unfair. There are good reasons for acknowledging that the class structure that is inherent in any capitalist or mixed society, is essential for the working of the modern economy. There is a potential trap in comparing the real (Britain today with all its class divisions) with the unattainable ideal (a utopia in which all class divisions have been eradicated). The ideal may be used to criticise the social structure of Britain, but it is arguably not something that could replace it. To acknowledge that there are divisions between the classes or to accept that the mobility between classes is not as great as some people make out, is not, in the final analysis to say that Britain is “unfair”. That requires further reflection and debate.

|

|

|

Finally, all of this is further complicated by transitions over time (the main one being the deindustrialisation of Britain), and by the increase of affluence, the decrease in the size of the family (changes to the structure of the family), the increase of property ownership, processes of embourgeoisement and proletarianisation, which may be going on simultaneously, the emergence of an underclass and other structural divisions between groups, such as those based on gender, race and ethnicity. A complete description of the social structure of Britain will never be a matter of simple classification, nor one that is free of all debate.

|

|