|

Theories of Poverty |

Structuralism or not |

|

Marxism (conflict structuralism) attributes poverty to the existence of class divisions in society. Poverty helps to maintain the domination of the bourgeoisie; it serves the interest of this wealth owning class.

|

|

|

Needless to say there are other sociologists of a “right-wing” persuasion who would disagree. They attribute the persistence of poverty to the poor themselves, arguing that as individuals they are to blame for their own poverty, or as groups they develop a culture of poverty that perpetuates their poverty.

|

|

|

It is not necessary to be a Marxist in order to agree that poverty is routed in the structure of society rather than in the individual. Also, it is possible to adopt an interactionist approach, arguing that the structure of society creates a culture of poverty among the poor, which perpetuates the structure of society, and so forth.

|

|

Individualistic theories |

|

The C19th sociologist, Herbert Spencer, blamed poverty on the poor. He claimed that the poor were lazy, and those who did not want to work should not be allowed to eat. He attributed poverty to bad moral character. He argued that the State should intervene as little as possible. It was he that coined the phrase, “the survival of the fittest”.

|

|

|

This attitude still prevails today, and Golding and Middleton claim that newspapers regularly report benefit claimants as “scroungers”. However, this attitude seems to be in some decline. According to a survey conducted by the European Commission into attitudes in 1976 43% of British people blamed poverty on laziness compared to 18% in 1989. Furthermore, Britain was the country where people were most likely to blame poverty on the individual characteristics of the poor.

|

|

|

According to American writer William Ryan this individualist theory is an example of “blaming the victims”.

|

|

|

The Thatcher and Conservative regime was associated with the “New Right”, who claimed that the benefits system created a culture of dependency. The sociologist David Marsland typifies this approach, arguing that low incomes are caused by the generosity of the state; additionally, public expenditure on income support withdraws money from investment in industry. He argues that benefits should be targeted at only those in “genuine need”, such as the disabled. He writes: “Critics of the universal welfare provision are not blaming the poor, as welfarist idealogues argue. On the contrary, these are the foremost victims of erroneous ideas and destructive policies imposed on them by paternalists, socialists, and privileged members of the professional New Class.”

|

|

|

However, Bill Jordan opposes Marsland, claiming that poverty is caused by a welfare system that is means-tested and too mean. The way to tackle poverty is to have “universal provision, which brings everyone up to an acceptable level. Far from creating dependence it frees people from dependence.”

|

|

|

Dean and Taylor-Gooby have also attacked the “myth” of a dependency culture. In addition to attacks on the theoretical basis of this idea, they also conducted research in 1990 based on in-depth interviews with 85 social security claimants in London and Kent. They found that (1) the vast majority of claimants wanted to work; (2) problems associated with the benefits system did discourage people from looking for work; (3) such disincentives did not lead to a dependency culture — people wanted to earn their own living and looked on the state only as their last resort.

|

|

The Culture of Poverty |

|

The concept of a culture of poverty was introduced by American anthropologist, Oscar Lewis, as a result of studying the urban poor in Mexico and Puerto Rico. The culture of poverty constitutes a “design for living” that is passed on from generation to the next. Individuals feel marginalized, helpless and inferior, and adopt an attitude of living for the present. They are fatalistic. Families are characterized by high divorce rates, with mothers and children abandoned; they become matrifocal families headed by women. People adopting this culture of poverty do not participate in community life or join political parties; they make little use of banks, hospitals and the like.

|

|

|

According to Lewis the culture of poverty perpetuates poverty: It “tends to perpetuate itself from generation to generation because of its effect on children. By the time slum children are aged six or seven, they have usually absorbed the basic values and attitudes of their subcutlure and are not psychologically geared to take full advantage of changing conditions or increased opportunities which may occur in their lifetime. However, Lewis regards the culture of poverty as applicable to Third World countries, or countries in the early stages of industrialization, and claims that it is not prevalent in advanced capitalist societies. But sociologists such as American Michael Harrington (The Other America) do argue that the culture of poverty can apply to advanced industrial societies. American anthropologist, Walter Miller, also argues in this way, claiming that the American lower class has its own set of focal concerns that emphasize masculinity, living for the present, and luck rather than effort as the basis of success. He regards this class subculture as self-perpetuating. He also claims that it is an adaptation to low-skill occupations. For example, people with this attitude have an increased ability to tolerate boring work and to find gratification outside work.

|

|

|

Some critics of the concept of a culture of poverty claim that their own studies do not provide evidence of it. For example, Kenneth Little's study of West African urban communities shows that the poor do participate in many voluntary associations. Similarly, William Mangin's study of Peruvian barrideas, people living in shanty towns, shows a high level of community and political involvement and a great deal of “self help”. J. Schwartz also finds in his study of slum areas of Venezuela little evidence of apathy and resignation. Charles and Betty Lou Valentine studied low-income black Americans and did not find evidence of a poverty of culture; or rather they concluded, “Apathetic resignation does exist, but it is by no means the dominant theme of the community.” Madge and Brown (Despite the welfare state) claim that “there is nothing to indicate that the deprivations of the poor, racial minorities or delinquents, to cite but three examples, are due to constraints imposed by culture.”

|

|

|

Another line of criticism of the concept of a culture of poverty is to explain the culture as a reaction to situational constraints. Lewis and Miller argue that the attitudes expressed by the culture of poverty are a reaction to low income and a lack of opportunity, so that if these causes would be removed, so would the culture of poverty. Hylan Lewis, an American sociologist, writes: “it is probably more fruitful to think of lower class families reacting in various ways to the facts of their position and to relative isolation rather than the imperatives of a lower class culture.” Sociologists arguing this situationalist explanation claim that the poor in fact share the same values as the rest of society, but their behaviour is a response to their perception of hopelessness in realizing these ideals.

|

|

|

Elliot Liebow's Tally's Corner, is a major contribution to this approach. He studied the life and culture of black “streetcorner men”. He argues that the habits of members of this group, such as blowing money on a weekend of drinking, are reactions to their knowledge of their situation: “He is aware of the future, and the hopelessness of it all.” Since he has a dead-end job and insufficient income, the streetcorner man is “obliged to expend all his resources on maintaining himself from moment to moment.” These men want to have a conventional family life, but their incomes are too low to support it. “To stay married is to live with your failure, to be confronted with it day in and day out. It is to live in a world whose standards of manliness are forever beyond one's reach.” In reaction to this hopelessness, the men develop a “theory of manly flaws”. Rather than blame the breakdown of their marriage on their lack of income and situation, they prefer to attribute it to their “success” as men — their need for sexual variety and adventure, for example.

|

|

|

The Swedish anthropologist, Ulf Hannerz, adapts Liebow's work. He argues in Soulside that whilst the theory of manly flaws is initially a reaction to a situation, it also becomes a self-perpetuating subculture. That is, “this model of masculinity could constitute a barrier to change.” Thus, even if the situational forces were removed, there could be a cultural lag, making the poor resistant to changes in culture.

|

|

The Underclass |

|

Charles Murray — the underclass in Britain

|

|

|

The idea of an underclass was first developed by right-wing, American sociologist, Charles Murray. He applied the concept to Britain during a visit in 1989. His idea is linked to theories that blame the individual for his poverty, and also to the concept of a culture of poverty. He writes, “When I use the term 'underclass' I am indeed focusing on a certain type of poor person defined not by his condition, e.g. long term unemployed, but by his deplorable behaviour in response to that condition, e.g. unwilling to take jobs that are unavailable to him.” Other kinds of “deplorable” behaviour include committing crimes and having illegitimate children.

|

|

|

So being a member of the underclass in this sense means having a deplorable subculture linked to not wanting to work. He primarily blames illegitimacy for this condition. In 1979 Britain has an illegitimacy rate of 10.6% but by 1988 this had risen to 25.6%. Illegitimate children are more likely to be born to women of lower social class. He claims that illegitimate children “run wild” because they lack father role-models. He claims that the underclass is responsible for rising crime — property crime and violent crime. These damage communities and make people withdraw into themselves. He claims that young men do not want to work and this causes a break-down in community life.

|

|

|

He blames the rise in illegitimacy on the benefits system. For example the value of benefits has increased and the 1977 Homeless Person's Act has made mothers a priority in the allocation of housing. The social stigma of being an unmarried mother has been removed, and hence the disincentives against it have been removed. Likewise, the crime rate has risen because criminals are less likely to be caught and if caught convicted. However, interestingly, he does not propose changes in the benefits system as a solution to the “problem” but rather argues that local communities should be given “a massive dose of self-government”.

|

|

|

Critics of Murray claim that there is no evidence for his conclusions. Alan Walker argues that Murray's claims are based on “innuendos, assertions and anecdotes”. Research into single mothers by John Ermish found that in the 1980s most women do not remain single parents. Walker states that members of the so-called underclass want jobs and stable relationships. Brown claims that divorced single mothers actually spend longer on average claiming benefits than never-married single mothers. Anthony Heath, by studying the British election Survey of 1987 and the British Social Attitudes Survey of 1989 found that there are no significant differences between the “underclass” and the employed in their attitudes to work and marriage, unless, perhaps, members of the underclass are slightly less likely than other people to believe that people should get married before having children.

|

|

|

Frank Field — Losing Out

|

|

|

A different concept of the underclass is put forward by British Labour MP Frank Field. He claimed that poverty is increasing in Britain, and that there is a growing underclass made up of (1) the long-term unemployed, (2) single-parent families; (3) elderly pensioners. This group is characterized by being reliant on state benefits that are too low to give them an acceptable living standard, and have no chance of escaping from reliance on state-benefits. The causes of the development of this “underclass” are rising levels of unemployment, changes in government policy under Thatcher, which have widened the gap between the rich and the poor, and changes in the public attitude to poverty, with an increase in the tendency to blame the poor for their poverty. In general he argues that Thatcher reversed the long-term trend in British social history towards the development of rights, and that the underclass are trapped by the lack of rights.

|

|

|

The Thatcher regime (1979 — 1990) removed the link between pensions and average wages; sick pay was phased out in 1980; child benefit was frozen in 1987 and 1988. The increase in means-tested benefits under Margaret Thatcher's successor as Prime Minister, John Major increased dependency and created a poverty trap. All in all, the gap between the rich and the poor increased during the period of Conservative government (1979 — 1997).

|

|

|

Thus Field blames government policy for the creation of an underclass, and therefore argues that changes in government policy will reverse the trend. (1) The unemployed should be placed on training schemes or (2) receive temporary work; (3) unemployment benefit should continue indefinitely for those seeking work; (4) income support should not include a spouse's earnings; (5) a minimum wage should be introduced.

|

|

Conflict Theories of Poverty |

|

Poverty and the Welfare State

|

|

|

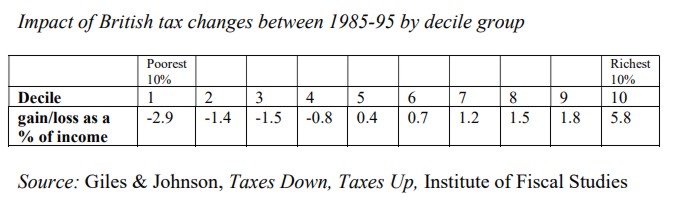

Since most of the people who are poor receive state benefits, it can be argued that the existence of poverty can be attributed to the inadequacy of these benefits. It is not in fact true that taxes generally redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor. Direct taxation is progressive and the rich pay more, but indirect taxation, such as VAT (Value Added Tax) is regressive, that is, the poor pay more proportionately. Also, the poor spend proportionately more of their income on alcohol and tobacco, on which the heaviest duties are levied, than the rich. In fact, since 1978/9 the tax burden on the poor has increased, whilst the tax burden of the rich has been reduced.

|

|

|

Impact of British tax changes between 1985-95 by decile group

|

|

|

|

|

The inequality extends to areas other than just income. Julian Le Grand, in Strategy for Equality, claims that the children of families with incomes in the top 20% receive nearly three times the amount of money spent on them as the bottom 20%. Poorer people are more likely to suffer from illness. However, Le Grand found that people on the highest levels of income receive 40% more NHS spending than people in the lowest decile. The DHSS report Inequalities in Health, which is also known as the Black Report (1981) stated that there was an inverse care law: public expenditure is inversely proportional to need.

|

|

|

Tax relief on mortgages also benefits the wealthier members of society, since those who do not own their homes cannot take advantage of the benefits.

|

|

|

In Michael Mann's review of changes in state policy, he found that whereas some of the benefits of the wealthy have been removed — for example, mortgage interest payments have been limited to the first Ł30,000 — other measures have been introduced that enable the rich to reduce their tax bills. For example Tax Exempt Special Savings Accounts (TESSA) and Personal Equity Plan (PEP).

|

|

|

Poverty and the labour market

|

|

|

A good proportion of the poor are employed, but receive wages insufficient to meet their needs. The unemployed and low-paid tend to be those who are unskilled. Increasing mechanization has reduced the demand for unskilled labour. Narrow profit margins in labour-intensive industries, such as catering, force wages down. Large families push people into poverty. However, this is not due to profligacy, as Coates and Silburn in their report on their study of a low-income group in Nottingham report: “For most families living on the borderline of poverty, it was the second or third child, rather than the fifth or sixth, who plunged them below it.”

|

|

|

This analysis is supported by the dual labour market theory, which is the view that there are two labour markets: (1) the primary market for skilled labour, which offers relatively high wages and job security; (2) the secondary market for unskilled labour, where there are low wages and little job security.

|

|

|

According to Dean and Taylor-Gooby, during the 1980s and 1990s demand for labour in the secondary market declined. This is because (1) there has been a decline in the number employed in the manufacturing sector with the development of deindustrialisation; (2) the new service sector jobs are not secure — many are part-time jobs with low pay; (3) unemployment struck some regions harder than others — the North, Scotland, Wales, the Midlands and Northern Ireland; (4) the power of the unions has declined, thus making workers more vulnerable, and depressing wages.

|

|

|

Poverty and Power

|

|

|

The poor lack political power. The employed are represented by trade unions. The lack of income of the poor means that they do not have the resources to organize effective protest. They also have no economic sanctions — the employed can strike, but the poor cannot. The employed do not identify with the unemployed, and members of the working class have prejudicial attitudes to the poor, seeing them as “scroungers” and “layabouts”. The poor are also handicapped by the shame of poverty — the poor are largely unseen. Ralph Miliband states that “economic deprivation is a source of political deprivation; and political deprivation in turn helps to maintain and confirm economic deprivation.”

|

|

|

Poverty and stratification

|

|

|

Conflict theorists claim that poverty is caused by the structure of society. Peter Townsend in Poverty in the United Kingdom claims that the existence of class divides is the major factor in causing poverty; but he also acknowledges that poverty is related to lifestyles. The poor also lack status, and low status groups also include retired elderly people, the disabled, the chronically sick, one-parent families and the long-term unemployed. Townsend also notes that international institutions contribute to the creation of poverty. For example, restrictions imposed by the International Monetary Fund, usually result in cuts in government expenditure and reductions in welfare programmes. On the other hand, European employment legislation sets a minimum wage. The use of cheap labour in Third World countries can cause poverty in First World countries.

|

|

|

Marxism and poverty

|

|

|

Marxists theorists do not draw a sharp line between the working class and the disadvantaged. They note that members of the working class can fall into poverty through unemployment. Miliband maintains: “The basic fact is that the poor are an integral part of the working class — its poorest and most disadvantaged stratum. They need to be seen as such, as part of a continuum, the more so as many workers who are not 'deprived' in the official sense live in permanent danger of entering the ranks of the deprived; and that they share in any case many of the disadvantages which afflict the deprived. Poverty is a class thing, closely linked to a general situation of class inequality.

|

|

|

Poverty and Capitalism

|

|

|

Marxists argue that the existence of poverty is beneficial to the ruling class. Poverty increases the motivation of the working class to work. Those in work also receive unequal rewards for work. The existence of low wages reduces the wage demands of the workforce as a whole. J.C. Kincaid claims that “from the point of view of capitalism the low-wage sector helps to underpin and stabilize the whole structure of wages and the conditions of employment of the working class.” Differentials in wages help to fragment the working-class; if wages were similar, greater unity and a single class-consciousness might be encouraged, with a possible threat to the capitalist class as a result. Kincaid states “It is not to be expected that any Government whose main concern is with the efficiency of a capitalist economy is going to take effective steps to abolish the low wage sector.” Westergaard and Resler attack the idea that the welfare state has led to a more equitable redistribution of wealth. Payments to the poor are generally levied from the working classes. They claim that a policy of “containment” is effectively pursued — the labour movement has been contained within the system. Kincaid believes “that some are rich because some are poor”. Marxists claim that the capitalist system creates poverty.

|

|

|

Herbert J. Gans has identified a number of functions that make poverty “useful” to capitalists. (1) Temporary, dead-end, dirty, dangerous and menial jobs are undertaken by the poor. (2) Poverty creates jobs and careers for middle-class people. Gans writes, “poverty creates jobs for a number of occupations and professionals that serve the poor, or shield the rest of the population from them.” These include the policy, probation officers, social workers, psychiatrists, doctors and civil servants. There is a “poverty industry”. These workers may be idealists, but they have a vested interest in the continuing existence of poverty. (3) Poor people make everyone else feel better. “Poverty helps to guarantee the status of those who are not poor.” He also says, “The defenders of the desirability of hard work, thrift, honesty and monogamy need people who can be accused of being lazy, spendthrift, dishonest and promiscuous to justify these norms.”

|

|