|

Family and Household Structure over Time |

The effect of industrialization on the family |

|

The pre-industrial society is pictured as one where people are divided into kinship groups called lineages each of which is held to be descended from a common ancestor. Another form of family in pre-industrial society is found in traditional peasant societies such as the Irish farming community studied by C.M. Arensberg and S.T. Kimball in their work Family and Community in Ireland. This traditional Irish family is a patriarchal extended family. It is also patrilineal since property is passed from father to son.

|

|

|

According to Talcott Parsons the isolated nuclear family is the typical form in modern industrial society. It is isolated from the extended family, and there is a breakdown of kinship. The development of the isolated nuclear family is, in his opinion, the product of a process of structural differentiation — the process by which social institutions become more and more specialized in the functions they perform. The isolated nuclear family is functionally necessary and contributes to the integration and harmony of the social and economic system as a whole. The family needs to be isolated because of its functional role in ascribing status. Status in industrial society as a whole is achieved and not ascribed. However, within the nuclear family status is ascribed rather than achieved, thus reversing the pattern that exists outside the family. What this means is that within the family the father has status as the father, whilst outside the family his status might be very different. His achieved status economically does not affect his status as a father. However, if the family was extended then a conflict could arise.

|

|

|

Another way of putting this is that the family ascribes particularistic values whilst society ascribes universalistic values. The conflict between the two sets of values is minimized by the isolation of the nuclear family.

|

|

|

William Goode in World Revolution and the Family also argues that industrialization undermines the existence of the extended family. He claims this is because (a) movements of individuals between different regions; (b) higher levels of social mobility; (c) the erosion of the functions of the family, these being taken over by external organizations such as schools, businesses and the state; (d) the greater significance of achieved status undermining the value of status within the family and in kinship groups.

|

|

|

According to Goode members of a family engage in role bargaining. What this means is that they will maintain kinship relationships if such relationships bring them rewards commensurate to their efforts to maintain them. In fact, developments in communication and transport make it feasible to maintain kinship relationships, but in practice modern industrial society means that individuals gain more by rejecting kinship relationships than by maintaining them. He supports this point by noting how extended family patterns are more frequent among members of the upper classes since for individuals in the family maintaining family connections can bring economic benefits.

|

|

|

However, all of this assumes that pre-industrial societies exhibited a different form of family structure to post-industrial societies. This assumption has been severely challenged by the work of Peter Laslett, whose study of English society revealed that only 10% of households prior to industrialisation could be described as extended. This is the same percentage as for England in 1966. A similar pattern would seem to hold in America. Thus the evidence suggests that the classic extended family was not widespread in pre-industrial England.

|

|

|

Furthermore, Laslett does not accept that the pre-industrial nuclear family was peculiar to Britain. He argues that such a family type was common to Western Europe, citing evidence from northern France, The Netherlands, Belgium, Scandinavia, Italy and Germany. However, in Eastern Europe and other parts of the world the extended family was more common.

|

|

|

Brigritte and Peter Berger argue that the nuclear family was a cause of the development of modernity — that is, it paved the way for the evolution of industry, since it developed people who had more self-reliance and independence, which are qualities required of entrepreneurs.

|

|

|

Not everyone wholly accepts Laslett's interpretation. Anderson claims that some research does show the existence of a wider variety of family types, for example, in Sweden the extended family was very common. He does not accept the theory that a “Western family” type exists, but rather argues that in pre-industrial society there was a wide range of family types. His own research using census data for Preston in 1851 indicates that 23% of households could be categorized as “extended families”, even though this applies to a post-industrial stage of development. If this is the case, then industrialization does not necessarily bring about the demise of the extended family. However, a number of factors might make Preston unique, so the study cannot be taken as representative of working class families in general at the time.

|

|

|

The study by Elizabeth Roberts into family life in Lancashire used oral history techniques — that is interviews with people about their lives — in order to develop a picture of family life between 1890 and 1940. They also conclude that extended family relationships remained important in working-class families despite industrialization. It would appear that nineteenth century industrialization did not bring about the end of the extended family.

|

|

|

According to Michael Young and Peter Willmott in their book The Symmetrical Family the family in England has gone through four stages.

|

|

| (1) | | The Pre-industrial family. At this stage the family is the unit of production; husband, wife and children work as a unit in the production of agricultural items or textiles. |

| (2) | | The early industrial family. Members of the family are now employed as wage earners. This kind of family predominated in the C19th when wages were low and there was the threat of unemployment. Families responded by extending their network of relationships to include relatives. Women were largely responsible for this. There was a central relationship between a mother and her married daughter; by contrast the husband-wife relationship was weak. Women formed an 'informal trade union' from which men were excluded. This kind of family may still be found in long-established working-class areas. |

| (3) | | The symmetrical family. The nuclear family has become separated from the extended family and the 'trade union' of women has been disbanded. The husband is important once again within the family. Husband and wife share decisions, and work together, hence the term 'symmetrical'. This kind of family predominates more in the working classes than in the middle-classes. Work is important in shaping the nature of family life. |

| (4) | | The Stage 4 family. Young and Wilmott predict the development of a stage 4 family, which is an extension of their theory of the 'Principle of Stratified Diffusion'. According to this theory patterns of living diffuse down the social structure. Thus families at the bottom of the social order will copy the habits of those at the top. Applying this theory, they observe that managing directors lives are work centred rather than home-centred. For such men sport, such as golf, is an important area of recreation. The relationship has become asymmetrical again, with the role of the wife being to look after children. |

|

|

|

However, Willmott and Young, in their study of Woodford, a predominantly middle class suburb of London, claim to show that middle class families maintain contacts with their relations. Thus, the similarities between family lifestyles in the working class areas of Bethnal Green and the middle-class area of Woodford are more similar than might have otherwise appeared.

|

|

|

The family beyond the nuclear family provide services that are important. A study by Bell shows that aid from parents, particularly from a son's father, is very important during the early years of marriage. Graham made similar conclusions in his study of a commuter village in East Anglia in the early 1970s. The relationships within the extended family were marked by 'positive concern' for the welfare of kin and this did not depend on the frequency of physical contact between the members of the extended family.

|

|

|

Willmot's 1980s study of a north London suburb continues to show that both middle and working class families maintained contacts with kin. Contact is facilitated by the use of cars. Willmott's conclusion is that 'relatives continue to be the main source of informal support and care'.

|

|

|

Janet Finch has studied the extent to which families feel a commitment to help each other. According to her there is a myth of the 'Golden Age' of the family — a myth that in pre-Industrial societies family obligations were much stronger and members of a family helped each other more. Her research suggests that there was no automatic assumption that the family should be responsible for elderly relatives. In Finch's opinion what assistance that was provided was based on mutual self-interest rather than on selfless family obligations. She also maintains that in contemporary society kinship relationships still remain more important to people than other relationships.

|

|

|

All of these studies contradict Talcott Parsons's concept of the isolated nuclear family. It may be that American families are more isolated than British families; however, a number of American researchers also reject Talcott Parson's ideas. According to Sussman and Burchinal, the evidence from research in general is that the modern American family is not isolated. Parsons replies that the existence of kinship relationships outside the nuclear family are not inconsistent with this concept of the isolated nuclear family. This is because the nuclear family is structurally isolated, in the sense that it is not an integral part of the economic system, and that kinship relationships outside the nuclear family are a matter of choice. Rosser and Harris's Swansea study supports Parson's arguments in showing that there is a very wide variation in kinship relationships. Janet Finch's review of research on families also shows a very wide spectrum of relationships within families. According to Parsons extended families are not 'firmly structured units of the social system'.

|

|

|

For this reason Eugene Litwak has introduced the term modified extended family. According to him this is a “coalition of nuclear families in a state of partial dependence.” These families exchange services, but retain a higher level of autonomy than would be experienced within the classical extended family system. Willmott has also come to a similar conclusion in his concept of a dispersed extended family, in which two or more related families cooperate with each other despite living at some distance from each other.

|

|

Household types |

|

There is a distinction between a household and a family. A household is a unit that lives together in one residence and can comprise a single person. A family does not necessarily have to be living in one house.

|

|

|

Trends in household types

|

|

| (i) | | The average size of household in the UK has fallen from 3.09 in 1961 to 2.64 in 1983. The fertility rate in 1983 was 1.75. |

| (ii) | | Married couples with young children comprise only 30% of households in 1983. |

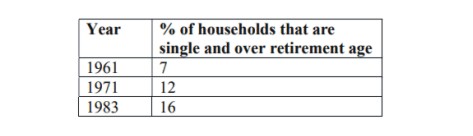

| (iii) | | There is an increase in the proportion of single people over retirement age.

|

| (iv) | | In 1983 27% of households are married people with no children. |

|

|

|

Trends in old age: 620,000 people were over 85 in 1983. By 2021 this is predicted to rise to 1,230,000.

|

|

|

Marriage and parenthood

|

|

|

90% of people marry. In the C19th there was a shortage of men, and 1/3rd of women of marriageable age did not marry. However, there are slightly more men than women among the young. The number of marriages reached a peak in the 1970s. Generally there has been a decline in marriage, but this trend has been slightly reversed in the 1990s.

|

|

|

Men tend to be slightly older than women when they marry. In 1982 the median age for men was 25.9 years and for women 23.5 years. In 1971 the median age for men was 24.0 years and women 22.0 years.

|

|

|

There is a trend towards cohabitation before marriage. In 1978 21% of married women between 16 and 34 years had cohabited, where the marriage was the first marriage, and 67% if one or both had already been married. In 1970-74, 8% and 46% were the relevant figures. Remarriages: 1961 — 15%, 1982 — 35% (where one or both partners has been married before). In conclusion there exists a continuing belief in marriage as an institution.

|

|

|

90% of married women have children. The average age of women when she has her first child is 25. Working-class women tend to have their first child at an earlier age than middle-class women.

|

|

|

15% of the adult population of childbearing age is infertile. There are 50,000 new cases of infertility each year. Infertility is on the increase because: (i) couples are delaying their attempt to have children; (ii) the effect of venereal disease on women; (iii) prolonged use of the contraceptive pill; (iv) increased use of drugs and chemicals in modern life.

|

|

|

Dual-worker families

|

|

|

1851: 24% of married women worked

1911: 13% of married women worked.

|

|

|

This decline between 1851 and 1911 reflected the dominant ideology of the late Victorian period that the role of women was located in the home.

|

|

|

1951; 21.7% of married women worked.

1982: 42.2% of married women worked.

|

|

|

The percentage of working women is likely to increase, making dual-worker families and increasingly important form of family.

|

|

|

According to Gowler and Legge, women work because (i) they need the money, (ii) they desire social contact; (iii) they develop personal identity in this way; (iv) they wish to contribute to society.

|

|

|

The increased percentage of working women affects (i) the pattern of childcare; (ii) the relationship of husband and wife.

|

|

|

Current nursery facilities are inadequate and employers are under no economic pressure to provide such facilities. Quality of childminders is variable. Some women adopt part-time work as a solution. Poor families experience greater difficulties than richer ones. Rich families can employ nannies and au pairs. Feminists believe that men have not fundamentally adjusted their outlook to accommodate to the fact that their wives work. This places a strain on marital relationships.

|

|

Family Diversity |

|

There is evidence to suggest that there is no one typical family type, and that societies have a plurality of households. If this is the case, the idea of a typical family is misleading. This idea is promoted by the 'cereal packet image of the family' which is typically of a happily married couple with two children, with a male breadwinner and a wife in a predominantly domestic role. According to Robert and Rhona Rapoport in their 1978 work only 20% of families conform to this type. The number of families with dependent children has declined from 38% in 1961 to 24% in 1992. Single person households have increased, and the number of single-parent families has also increased from 2.5% to 10.1% in the same period. There are similar trends on other European countries.

|

|

|

According to the Rapoports family diversity in Britain has five distinctive elements: (1) There is organizational diversity, meaning that there are differences between conventional families, one-parent families and dual-worker families. This organizational diversity is also increased by the increasing proportion of reconstituted families. (2) There is ethnic diversity. (3) There are diversities based on class. (4) There are diversities based on the stage the family is at in the family lifecycle. (5) Families may be affected by the cohort to which they belong. For example, children of families that entered the labour market in the 1980s may have spent more time at home because of the high unemployment at that time.

|

|

|

Another source of diversity is regional diversity. This is the objective of work by David Eversley and Lucy Bonnerjea. According to them the 'sun belt' region of south England has families that can be called family builders — upwardly mobile families. The coastal regions are 'geriatric wards'. In regions suffering from long-term structural decline, families adopt conventional and traditional structures. Inner city areas have more one-parent and ethnic minority families. The newly declining industrial areas of the Midlands have a range of family patterns. Truly rural communities have strong kinship networks.

|

|

|

According to the Rapoports more and more people are choosing their family lifestyle. People no longer feel constrained to follow one norm. It is recognized that there is a plurality of norms.

|

|

|

Increasing one-parent families

|

|

|

Government statistics show that in 1961 2.5% of families were single parent families with dependent children, whereas in 1991 the percentage had increased to 10.1%. Between 1972 and 1991 the percentage of children in single-parent families increased from 8% to 18%. According to the Rowntree Foundation in 1989 lone-parent families made up 14% of all British families.

|

|

|

Trends in One-parent families: In 1961 2% of families were one parent; in 1983 5% were. In 1983 there were 1 million one-parent families, with 87.4% headed by a woman and 12.6% headed by a man. Of lone mothers, 16.2% were widowed, 21% were single, 23.8% were separated, 39% were divorced. The average age of the lone mother was 27 years, of separated mothers, 37 years, and of widowed mothers, 49 years.

|

|

|

The vast majority of single parents are women. The General Household Survey of 1990 indicated that 18% of families had a lone mother, but only 2% of families had a lone father. The increase in the incidence of divorce accounts for this trend. In 1971 the proportion of lone mothers who were divorced was 21%; in 1991 the proportion was 43%. At the same time the proportion of lone mothers who were widows was falling.

|

|

|

There is no evidence that single parents prefer to be single parents. In Britain Conservative politicians in the past have expressed concern that single parents “sponge” off the state, but there is little evidence to suggest that single parenting is preferable from an material point-of-view! In fact, according the Charles Murray single parents are more likely to belong to the underclass. Single parenthood is associated with low income and low living standards. Single parents are less likely to own their own homes and more likely to live in council accommodation.

|

|

|

According to Sara McLanahan and Karen Booth in their American studies, children of single parents are disadvantaged. They tend to have lower earnings, and to experience more poverty as adults. They are more likely to become single parents themselves. They are also more likely to become delinquent and to be involved in drug abuse. These effects, however, are the products of low income rather than single parenting as such.

|

|

|

Ethnic diversity

|

|

|

Immigrants from different cultural backgrounds have different family forms than those of the indigenous population. Asian families, for instance, are more likely to have families comprising three generations, and less likely to have households of single persons. West Indian households have a higher proportion of lone parents. In 1989-91 51% of West Indian mothers were lone mothers.

|

|

|

For Asian families, migration may have strengthened family ties rather than weakened them. Immigrant families have to confront the apparent lack of value British families attach to kinship and family honour, and in reaction they become more conservative about their own values. Likewise, children in these families did not reject these conservative values. For example, children might expect to have more say in the question of their marriage partners but they were not against the idea of arranged marriages. Asian families maintained links with their villages of origin in Asia.

|

|

|

According to Jocelyn Barrow there are three main types of West Indian family in the Carribbean. (1) The conventional nuclear family — which is similar to the nuclear family in Britain. These tend to occur when religion is strong or the family is prosperous. (2) Common-law families. An unmarried couple cohabits. They look after children that may not be biologically theirs. This type of family is found among less economically successful groups. (3) The mother household — where a mother or grandmother heads the household and it usually contains no adult males.

|

|

|

Research indicates that these three family forms are also typical of British families of West Indian origin.

|

|

|

Counter-arguments

|

|

|

According to Robert Chester the extent to which families are changing is exaggerated. “Most adults still marry and have children. Most children are reared by their natural parents. Most people live in a household headed a married couple. Most marriages continue until parted by death. No great change seem currently in prospect.”

|

|

|

Chester points out that how the statistics are presented can distort the conclusions. If numbers of types of households are counted this appears to show that there is an increasing diversity of household types. However, if numbers of people living in a household are counted, then this diversity is decreased. This is because families contain more people. For example, in 1981 40% of households had parents and children but 57% of people lived in such households.

|

|

|

Chester also points out that the family lifecycle means that people will not always belong to a nuclear family. Most people experience a parent-children household at some stage in their life. He acknowledges that women are taking paid employment and calls this kind of family the neo-conventional family.

|

|

|

Nonetheless, in 1981 57.7% of people lived in families with parents and children compared to 50.8% in 1992. So there is a slow drift away from the nuclear family. Kathleen Kiernan and Malcolm Wicks conclude, “Although still the most prominent form, the nuclear family is for increasing numbers of individuals only one of several possible family types that they experience during their lives.”

|

|