|

The Economic Problem |

Scarcity, choice and the basic economic problem

|

|

Economic systems produce goods, allocate them and distribute them.

|

|

|

However, the resources available to produce goods are scarce — this means, limited in supply. Therefore, there is a basic economic problem, which is the problem that scarce resources have to be allocated between competing uses. This involves people making choices over how to do this. For example, should a government spend tax revenue on defence or on education?

|

|

Opportunity costs

|

|

The allocation of scarce resources to one activity (say, education) rather than another (say, defence) creates benefits. The benefits can be measured in terms of physical output (production) or in monetary terms (the value, in money terms of the physical output).

|

|

|

Allocation of resources results in sacrifices. If we spend resources on education rather than defence we forego the benefits of the additional defence. The benefit lost from making one choice rather than another is called by economists its opportunity cost. If you have money to buy just one newspaper, and choose the Financial Times rather than The Telegraph, then the opportunity cost of buying the Financial Times is the benefit that you would have gained from buying The Telegraph.

|

|

Production possibility curve and productive efficiency

|

|

It is possible to allocate resources efficiently, or inefficiently. An efficient allocation of resources to the production of goods, results in the maximum amount of those goods being produced at the given time. Resources can be wasted, for example, through corruption or incompetence.

|

|

|

The idea of opportunity costs is illustrated by means of a production possibility curve. This curve represents the allocation of resources between, for example, two completing goods.

|

|

|

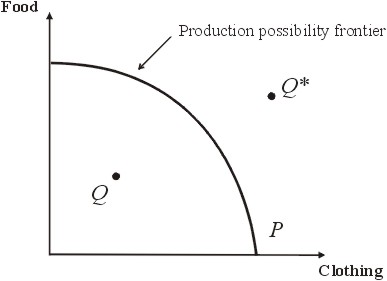

The curve is a “frontier”, showing the most efficient allocation of resources. Along this frontier there is productive efficiency. For example, suppose in a given country only two goods are produced, food and clothing. Then the graph of the production possibility frontier shows the maximum of each good that can be produced using all the resources of the country at maximum efficiency.

|

|

|

|

|

Example of a production possibility frontier.

|

|

|

This country produces only food and clothing. Along the frontier there is maximum productive efficiency. Any point within the region, say Q, is a point where the resources are not used efficiently. Any point outside the region, Q*, is a point which is not attainable using the resources of the country within the limitations of the productive techniques available at the time.

|

|

|

The diagram shows that in order to produce more food, some production of clothing must be given up, and vice versa. So this shows that there are opportunity costs involved in making any decision regarding the allocation of resources.

|

|

|

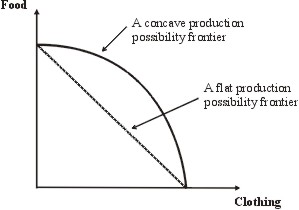

It is normal to represent the production possibility frontier as outwardly bulging (concave) rather than as a straight line.

|

|

|

|

The production possibility frontier bulges outward

|

|

|

This is because some resources are better adapted to the production of one good rather than another. For example, some land is not very suitable for farming — it would be better to use it for a textile manufacture; some people are better are making clothes than at farming. So as a country specialises more and more in the production of just one good, the opportunity cost in terms of the lost production of other goods rises.

|

|

Growth and the factors of production

|

|

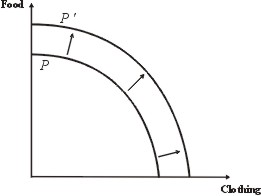

The production possibility curve can also be used to illustrate the idea of growth. This is shown by outward shifts of the production possibility curve.

|

|

|

|

An outward shift of the production possibility frontier

|

|

|

The production possibility curve shifts outwards from P to P?. This means that the economy has increased its productive potential.

|

|

|

To understand how growth can occur, we need to consider the factors of production.

|

|

|

Economists observe that in the production of any good, four factors of production are involved. These are:

|

|

| 1 | | Land

The physical land, but also comprising all the natural resources on the earth, below the earth or in the atmosphere. There is a distinction between renewable and non-renewable resources. Renewable resources are those that can be used and replaced. For example, water in a lake can be used, but can also be replenished. Non-renewable resources are those that once used cannot be used again. For example, coal and oil.

|

| | |

| 2 | | Labour

This is the workforce of the country. Each worker has a certain capacity to produce based on inherent characteristics such as intelligence, physical strength and emotional stability, and also acquired skills produced through education and training.

|

| | |

| 3 | | Capital

This comprises the stock of manufactured tools, machines, and other man-made resources, such as roads and railways, that are used in the production of goods and services. (It is worth noting that the term “capital” has many meanings. This is the economists' use of the term, and should be distinguished from “capital” in the more popular sense of “lots of cash”.)

|

| | |

| 4 | | Enterprise

Entrepreneurs are individuals who organise the other factors of production to make goods and services. They also take risks with their own money and the financial capital of others. |

|

|

|

Growth can occur because one or more of the factors of production can increase. New resources can be discovered; land can be reclaimed; the workforce can be upskilled, so that each worker is capable of producing more per hour of effort; the capital of the country can increase; and the total organisation of the factors of production, through enterprise, can improve. Technological change, as a result of enterprise, can result in better production techniques.

|

|

|

Of course, a country can also suffer negative growth; for example, a war may result in the destruction of labour and capital, and may result in land becoming useless for production.

|

|

The division of labour and specialisation

|

|

Production becomes more efficient when there is a division of labour. For example, imagine three men all making nails. Suppose the manufacture of nails requires three processes — (a) the drawing of a wire; (b) the sharpening of the point; (c) the pressing of the head of the nail. Each man performs all three processes. However, now suppose that each man specialises on just one task; then it is generally recognised that they will as a result produce more nails per hour in this way, then they did before specialisation. Thus, specialisation, which is the same as the division of labour, results in increased productivity. (When tasks are divided in such a way as they become boring, mechanical and repetitive, this can result in workers becoming emotionally dissatisfied with this work. We may generally call this “alienation”. Alienation is demotivating, so this could cause a loss of productivity, since demotivated workers do not necessarily produce as much as motivated ones.)

|

|

|

Labour productivity is the output of a worker per unit of time — for example, per hour.

|

|

Efficiency and equity

|

|

Efficiency is concerned with the allocation of resources to production. It is not concerned with how income is distributed.

|

|

|

The term equity is concerned with how income is distributed. It is concerned with fairness. Equity is the economists' term for fairness.

|

|

|

Equity is not the same as equality. Or rather, whether it is the same, depends on your point of view. For example, we can ask the question, “Is it fair that some people in this country should earn more than others?” Some people would answer “yes” to that question, and others would answer, “no”. Thus, for some, equity is the same as equality, and for others, it is not.

|

|

Positive and normative statements

|

|

The statement, “It is not fair that some people should earn more than others” is an example of a value judgement. It expresses an judgement about what is good or bad, right or wrong. Economists call such statements normative statements. By contrast, they maintain that, irrespective of what values a person may hold, it is possible to describe objectively and impartially the economic decisions that people take in a given situation. Such statements would be scientific in nature. They are called positive statements by economists.

|

|

|

It is not really possible to study economics without making normative statements. In other words, each student of economics will develop, over time, a set of beliefs regarding how their country, or the world, should be organised, as opposed to how it actually is organised. Nonetheless, much of modern economics concentrates on making positive and hopefully impartial, objective statements about how economies actually do operate.

|

|

Markets versus planning

|

|

|

In economics the most fundamental normative question that we face is the degree to which we believe economic decisions should be planned or left to markets.

|

|

|

We have already seen that an economic system is a mechanism whereby resources are allocated to the production of goods, and by which the output of the country is distributed to consumers.

|

|

|

A market is any arrangements whereby buyers and sellers communicate with each other in order to exchange goods and services.

|

|

|

There are two extreme forms of economic system: (1) the free-market system in which the allocation of resources and the distribution of finished goods and services is determined solely by the interaction of supply and demand through the market mechanism. (2) The command economy in which the allocation is determined by the state, theoretically on behalf of society as a whole. In a command economy central planners determine both the allocation of goods and the distribution of incomes.

|

|

|

However, every economy in the world is an example of a mixed economy. In no actual economy is every allocation of resources, goods and services determined solely by central planners, and in no actual economy does the state entirely leave markets to determine the allocation of resources, goods and services.

|

|

Systems of ownership

|

|

Capitalism is a system which permits the private ownership of the means of production.

|

|

|

Socialism is a system in which the resources used for production are owned by society as a whole.

|

|

|

Thus, capitalism does not mean by definition a free-market system, nor does socialism mean by definition a command economy. However, capitalism is associated in practice with a free-market economy, and socialism is associated in practice with a command economy.

|

|

|

For practical reasons, however, a capitalist economy may introduce a command economy. For example, during World War II, the UK, which remained a capitalist country, introduced a high measure of central planning as government made decisions as to what to produce and how goods and services would be distributed. On the other hand, socialist countries do also use markets as a means of allocating resources within the overall framework of a centrally planned economy.

|

|

|

However, as already noted, all economies are mixed economies, and likewise, all economies of the world exhibit features of both capitalism and socialism, though there are differences in the balance between different countries.

|

|

Planning failure

|

|

It is often claimed that centrally planned economies exhibit planning failure: (1) production is not guided by consumer preferences, and resources are consequently not used productively efficiently. This is because the price mechanism is essential to achieving optimum supply. (2) The absence of a profit motive makes production inefficient. Managers are not forced by market realities to seek for the most cost effective methods of production. (3) Inequalities of income are essential for economic efficiency. In order to motivate people to do all the jobs that need doing, there have to be differentials between wage incomes. It is claimed that in planned economies wage differentials are insufficient to achieve optimum motivation. Consequently, everyone in a planned economy may be closer to the average, but the average is very much lower.

|

|

Market failure

|

|

However, market economies may also fail to allocate resources efficiently. In fact, the study of how and why markets fail in this way forms a large part of the study of economics. Any failure of the market to allocate resources efficiently is called a market failure.

|

Economic models

|

|

Economists are concerned with explaining how scarce resources are allocated in an economy. In order to do so, they make assumptions about how people make economic decisions.

|

|

|

Two of the fundamental simplifying assumptions economists make about people are as follows:

|

|

| 1 | | The profit motive

Economists assume that the decisions taken by entrepreneurs (and the owners of businesses) are motivated by the desire to maximise profits (at least, in the long-run). In practice, this might not be entirely correct. In most large modern businesses the owners of the business, who are shareholders, do not manage the business. The owners want maximum profits, but the managers do not necessarily want this. They may have their own objectives — for example, the objective to protect their jobs. This leads to the managerial theory of profit satisficing — that is, the managers will produce sufficient profits to satisfy the shareholders, and thereafter pursue their own objectives. However, despite this observation, most economist explanations for the behaviour of managers of businesses (firms) are that they seek to maximise profits.

|

| | |

| 2 | | Maximising utility

Utility is the economists' term for the satisfaction derived from consuming a good. Economists generally assume that consumers seek to maximise their utility. For example, a consumer will spend his income so as to maximise his/her satisfaction from it. This is also a simplifying assumption, and one that assumes that people are solely concerned with consumption. In practice, people have a host of motives, and some of these may cause them to dispose of their incomes in ways that do not result in the maximisation of utility.

|

|

|