|

Competition Policy |

Privatisation |

|

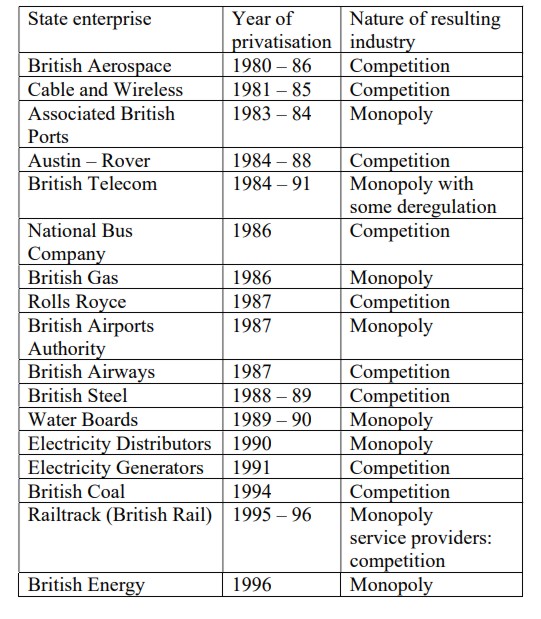

Privatisation is the process of transferring state monopolies to private ownership. Between 1979 and 1996 the British government sold £50bn of state assets. The major British privatisations were as follows

|

|

|

|

|

Privatisations of British industries, 1980 — 1996

|

|

Philosophical justification for privatisation |

|

It was believed that nationalised (state-owned) industries were prone to X-inefficiency. They were characterised by overmanning and inefficient bureaucratic processes. The aim of privatisation was to introduce the discipline of the market to these industries; to force newly privatised industries to cut out inefficient practices in order to achieve greater profits; to introduce the profit motive into these industries.

|

|

|

In addition, it was argued that the privatisation of state-owned industries would result in reduction in public spending. Private enterprise and private capital would take over the role of government in providing capital expenditure (investment) in these industries.

|

|

|

The Conservative Party, lead by Margaret Thatcher, also wished to widen share-ownership in Britain. This could be for philosophical reasons — a belief in a “property owning democracy”, or for political reasons — those who owned the shares would be more likely to vote Conservative at a future election. They may also have believed that in widening share ownership they may foster an enterprise culture.

|

|

The privatisation of natural monopolies |

|

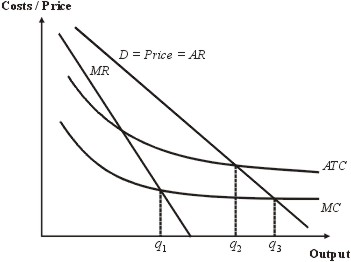

There is a particular problem is privatising a natural monopoly. A government is thought to aim at allocative (Pareto) efficiency; but allocative efficiency cannot be profitable. A privatised natural monopoly cannot both (1) earn profits, and (2) be allocatively efficient. We can show this as follows.

|

|

|

|

|

Natural monopoly

|

|

|

The profit maximising position is . This is at q1; but this is not the position of optimum allocative (Pareto) efficiency.

|

|

|

Optimum Pareto efficiency occurs when the sum of the marginal costs is equal to the sum of the marginal benefits. Since the marginal cost curve for the industry is the same as the marginal cost curve for the firm (since the firm is a monopoly), and since the price is proportional to the marginal social benefit, Pareto efficiency occurs when in the above sketch; that is at q3. (In this case we assume that there are not external costs or benefits.) But at this position, because of the way the MR curve falls faster than the AR curve, the monopoly would make a loss. At q3 the AR curve is below the AC curve, so it costs the company more on average to make each unit of output than they can charge for it, so a loss is made.

|

|

|

Another alternative is given by q2. Here AC = D. This is the position at which the natural monopoly makes no supernormal profits. However, companies in private ownership will endeavour to make supernormal profits, and will opt for the profit maximising position, which is at MC = MR.

|

|

|

The government may decide that allowing private monopolies to make supernormal profits is wrong. One way to correct this form of market failure is to take the monopoly into public ownership. This is called nationalisation.

|

|

|

However, recently there has been a move away from nationalisation. It has been felt that state run monopolies are bureaucratic, and that the benefits of private ownership can be passed onto the consumers, provided the monopoly is closely regulated. With this in mind, governments have privatised state owned monopolies.

|

|

UK regulatory policy |

|

In order to prevent private monopolies from exploiting their monopoly power to introduce higher prices without efficiency savings, private monopolies must be regulated by government appointed “watchdogs”.

|

|

|

There are two approaches to regulating a private monopoly. In the USA regulators concentrate on profits and place a cap on these. In the United Kingdom regulators concentrate on prices and impose a price formula.

|

|

|

UK regulators would argue that imposing a cap on profits creates no incentive to privately owned monopolies to improve efficiency. The permitted profit can be made either by an efficient or by an inefficient industry. Any efficiency savings cannot benefit the owners of the privatised monopoly. Therefore, the idea behind a price formula is to provide an incentive to the management of the monopoly to introduce efficiency savings leading to greater productivity. The formula divides the profits arising from improved productivity between the company and the consumer.

|

|

|

Thus the UK has regulatory bodies to control the privatised monopolies. These are OFTEL, OFFER, OFGAS and OFWAT for telecommunications, electricity, gas and water respectively.

|

|

|

They apply a price formula in the form of

|

|

|

Price = RPI − x

|

|

|

where RPI is the retail price index, and x is a factor that represents potential efficiency gains. In other words, privatised monopolies are expected to raise prices below the headline inflation figure, and any profits, supernormal or not, can only be made from efficiency (productivity) gains.

|

|

|

But there can be exceptions. At the outset of privatisation of the water, the water companies were permitted to raise prices above RPI so as to provide funds for investment. This is because it was recognised that the provision of water supplies had been under-invested for a period of time before privatisation took place, so it was “fair” to allow the privatised companies to recoup the cost of the investment they would have to undertake in order to bring the provision of water back to full efficiency.

|

|

|

The effectiveness of the regulatory bodies is often criticised. For example, the Yorkshire Water company is often cited as an example of a monopoly that seemed to abuse its monopoly power. In 1996 there were water shortages and a hosepipe ban and £47m was used to pay for a round-the-clock tanker operation to bring water to West Yorkshire during a drought. However, in 1995/6 the pre-tax profits of the company were £162.2m, which was £20m above that of the previous year.

|

|

|

There is the threat of regulatory capture. This occurs when the regulatory body that is supposed to be regulating a monopoly is infiltrated by the monopoly itself, and instead of serving the interests of the public, it starts to serve the interests of the owners of the monopoly. Really, this is a form of corruption, which is an inherent danger in any society. Regulatory capture can occur in more insidious ways. The regulator may rely on information passed to it by the company it is regulating. It is possible that the regulator may come to believe that the information it is receiving is comprehensive and impartial when it is not. Because it uses this information to make its decisions it may unwittingly be serving the interests of the company rather than the public.

|

|

Competition Law |

|

In addition to regulating formerly state-owned monopolies, the government endeavours to prevent private enterprise evolving further monopolies. Monopolies can develop in a free-market system through (1) the increasing dominance of one firm in a given market through its success in marketing its products; (2) the horizontal merger between companies in the same industry, or when one company acquires another through a takeover bid.

|

|

|

An example of (1) would be the evolution of the near world-wide monopoly in computer operating systems attained by Microsoft. This has largely been through Microsoft's success in gaining ever increasing market share. And example of (2) would be the merger of Boeing, McDonald and Douglas aircraft manufacturers into the single giant Boeing-McDonald-Douglas Corporation, the world's largest company, and effectively controller of a monopoly in the manufacture in passenger aircraft.

|

|

|

Companies that have monopoly power can exploit that power to impose higher prices on consumers without improvements in efficiency. Therefore, governments seek to prevent mergers that lead to market dominance.

|

|

|

In the UK the Monopolies and Mergers Commission (MMC) investigates cases referred to it by the Office of Fair Trading (OFT), which supervises competition and consumer law.

|

|

|

The UK government is concerned with regulating markets and preventing the threat of large firms acquiring monopoly power. In the United States monopolies have been regarded as illegal for over a century. Therefore, according to US anti-trust legislation any monopoly that develops should be broken up. Even so, despite many legal battles, the Microsoft monopoly has not yet been dismembered.

|

|

|

In the UK, since it is market dominance which poses the threat to competition, (1) a monopoly is deemed to exist when one company controls at least 25% of the market; (2) An investigation by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission can be conducted where two companies together control at least 25% of the market; (3) Mergers resulting of gross assets in excess of £30m or in control of at least 25% of the market can be investigated; (4) The Director General of Fair Trading working from the Office of Fair Trading has responsibility for overseeing competition policy. The Director General of Fair Trading has the power to refer investigations to the Monopolies and Mergers Commission.

|

|

|

However, the regulation of monopolies by the Monopolies & Mergers Commission has been critised. For example, in April 1996 there was a scandal over the inaction of the Monopolies & Mergers Commission's failure to investigate two proposed takeovers of regional electricity distributors by the electrical power generators. PowerGen proposed to take over Midlands Electricity, and National Power proposed to take over Southern Electric. These takeovers would have restricted competition, raised entry barriers to the industry, and have made the industry more difficult to regulate. Prices would have increased, and yet the MMC (Monopolies & Mergers Commission) failed to intervene, arguing that strong domestic companies are more able to compete for foreign markets. However, the Secretary for State, Ian Lang, intervened and blocked the takeover.

|

|

|

European legislation also governs competition policy. Article 85 of the Treaty of Rome makes it illegal for companies to enter into agreements that restrict or distort competition with the European Union, that is, by means of price fixing or agreements over market share. Article 86 also makes it illegal for a dominant firm or group of firms to exploit consumers. Articles 92-4 make it illegal for governments to provide subsidies which distort competition between industries or individual firms.

|

|

Collusion and cartels |

|

Collusion is the term used when firms seek to restrict competition by making agreements between them. They do this by forming a cartel — this is a group of producers who have decided on how the market is to be divided between them. In this way they can all charge higher prices and earn supernormal profits.

|

|

|

In fact, the formation of a cartel is not easy. There is always a tendency for a cartel to break down. Firstly, the companies must make an agreement. Once an agreement has been reached, it is always in the interest of any one company to cheat, so the participating companies must have some way of preventing this. Finally, since the companies make abnormal (supernormal) profits, they must be able to prevent new entrants to the market, for otherwise their profits will be eroded.

|

|

|

The fragility of a cartel is illustrated by the formation and destruction of the international cartel in coffee. Between 1962 and 1989 a cartel called the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) was formed between the major world producers of coffee beans. However, the supernormal profits that arose attracted African countries into the market, as a result of which Brazil saw its market share decline from 40% in 1962 to 24% in 1988. In 1988 Brazil left the cartel in a bid to drive coffee prices down and push out the other producers. However, they failed to do so. The cartel has so far not been reformed.

|

|

|

Cartels and collusive practices are bad for competition, for consumer prices and for efficiency. Therefore, governments legislate against their formation. It is illegal for companies to form a cartel and any trade agreements between companies must be published.

|

|

Restrictive trade practices |

|

The term restrictive trade practice is used for any strategy used by producers to restrict competition within a given market. Collusion resulting in the formation of a cartel is one such practice. Other practices that fall short of the formation of a cartel but are nonetheless against the public interest and illegal include: (a) the setting of minimum prices; (b) agreements to share markets; (c) the refusal to supply retailers that stock the products of other competitors; (d) setting different prices for different buyers (discriminatory pricing); (e) exchanging information.

|

|

|

The aim of restrictive practices is to raise prices and restrict output to the benefit of the companies practicing them.

|

|