|

Factor immobility |

What is factor immobility? |

|

Factor immobility occurs when a factor of production cannot move easily from one region of an economy to another. The obvious example concerns the movement of labour. Suppose, for example, there is an increase of demand for labour of all kinds in London, whilst the North of England experiences a decline in demand. Other things being equal, workers will migrate from the North to London in order to take up the jobs on offer there. However, many things may arise to hinder this process. For example, (1) there could be a lack of information; workers in the North of England might not know that they could get well-paid jobs in London; (2) There could be a lack of housing; workers that migrate to London may not be able to find accommodation, or the cost of renting the accommodation could erode the increased benefits of taking the job in London; additionally, they may not have enough money to provide a deposit for rented accommodation. Any one of these factors may prevent workers from migrating; (3) Workers in the North of England may have a different culture from those in the South; workers may be reluctant to leave their communities behind and learn a different way of living.

|

|

|

The movement of capital can also be restricted, resulting in factor immobility. However, where there is a single currency union, such as operates throughout the United Kingdom (with sterling) or through the European Union (with the Ecu), this does not tend to be a problem. Barriers to the free-flow of capital can exist between different currency unions. Some countries may prevent their currency being exported abroad by legal measures. To study this further we need to look at the theory of the gold standard — that is, the theory of fixed exchange rates.

|

|

|

Factor immobility arises from structural imperfections in an economy. In an ideal economy there would be impedance to the free flow of labour and capital from region to region or from sector to sector. In practice, however, bottlenecks develop in the flow of both, the result is unemployment.

|

|

Unemployment |

|

There are various types of unemployment:

|

|

| (1) | | Frictional unemployment — when people change jobs they may be unemployed for a while between jobs. |

| (2) | | Seasonal — there is generally more work available during summer months than during winter months. |

| (3) | | Cyclical or demand deficient unemployment — according the economist Keynes there is the possibility that there is insufficient demand for goods in the economy as a whole, which leads to unemployment. It is generally accepted that there was a lack of demand during the great depression of the 1930s. |

| (4) | | Structural unemployment. Each economy has a “structure”. This structure comprises the nature of the economy, which industries are key to the production of wealth, exports and so forth. From time to time the structure of the economy changes. When this happens, people may be employed in industries the products of which are no longer in demand. There will follow unemployment in these industries. Labour (and capital) involved in these industries needs to transfer to other new industries or services. However, this cannot happen “overnight”. It takes time, for example, to train miners to become bank-clerks. In fact, it may take generations. In the meantime, while labour retrains, there is structural unemployment. |

| (5) | | Residual unemployment. This describes the unemployment that arises when people are unwilling to work or unable to work owing to a disability. |

|

|

|

Frictional and structural unemployment can be seen as products of market failure. For example, if the flow of information was perfect then there would be no frictional unemployment.

|

|

Deindustrialisation |

|

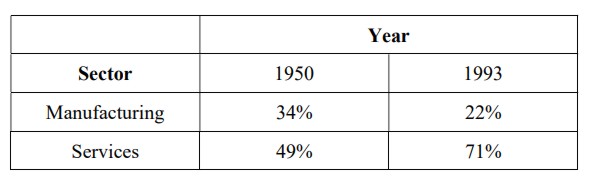

The following table shows comparisons of the people employed in Britain in the manufacturing and service sectors of the economy between 1950 and 1993.

|

|

|

|

|

This table might suggest that there was a decline in manufacturing in the British economy. In fact, manufacturing output in 1994 was 16% greater than manufacturing in 1950, but the services were 70% greater.

|

|

|

In other words, whilst the recession of 1979-81 reduced manufacturing below its 1970 level, over the last 35 years, taken as a whole, there has been some growth in manufacturing output. Nonetheless, the growth of the British economy has been in the service sector.

|

|

|

This process, whereby the proportion of the population in an economy employed in manufacturing declines is called deindustrialisation.

|

|

|

Deindustrialisation represents a substantial change in the structure of employment in the country. Therefore, it is likely to give rise to structural unemployment owing to factor immobility. One interpretation of the 1979-81 recession is that it arose from the surfacing of structural imperfections in the economy indigenous to the British economy from prior to the First World War. Major industries — coal-mining, steel manufacturing, shipbuilding and textile manufacturing — have been in long-term decline from the beginning of the C20th.

|

|

Recent British economic history |

|

The recent economic history of Britain illustrates the importance of structural unemployment. The period from 1947 to 1965 was generally a boom period masking underlying problems and rigidities in the labour market. The need to rebuild the economies of Western Europe following the war and the labour shortage meant that there were favourable conditions for steady growth and the period saw an unprecedented period of low inflation, low unemployment and high growth. However, the underlying situation in Britain was serious, and the events of the 60s and 70s brought these problems to the fore. As memories of the 1930s faded unionists became less worried about job security, and more willing to press for increased wages. Trade union power certainly increased during this period.

|

|

|

Furthermore, British industry and infrastructure was old, and in need of reinvestment. Attitudes in British industry were lacking in dynamism. There was the assumption that inferior manufactures would always find a market. Globalisation was also operating. Globalisation refers to the development of global markets for goods, services, capital and labour. It is caused by the increasing capitalisation of the largest multinational companies, by falling transport costs, and reducing tariff barriers, owing to trade agreements and the effects of successive rounds of GATT. In effect, globalisation means that a U.K. worker competes more directly for work with people in the Asian region. Thus the pressure on real wages, in the absence of improvements in productivity, must be downwards. If trade union power is such that falls in real wages can be resisted, the consequence is that unemployment must rise. If governments spend money, they will temporarily lift the economy at the expense of creating inflation. This is what happened to Britain. The problem cannot be attributed only to trade-union power. Responsibility for the poor record in Britain for investment, and the poor productivity record lie with management as well.

|

|

|

A further cause of instability in the British economy stemmed from the decision in 1973 to join the EEC. This was inevitable and essential, but occurring too late it was bound to lead to some restructuring of the economy. British industry came into direct competition with European industry. At the same time, the creation of a tariff barrier with former Commonwealth countries, meant an increase in food prices, and this may well have led labour to be more pressing in their wage demands.

|

|

|

The problems were already integral to the British economy before the major shock of the increase in oil prices following the Yon Kippur War in 1974. [In 1974 the Egyptians and Syrians attacked Isreal. At the same time Arab nations sympathetic to Egypt and Syria formed OPEC — the organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries. They raised oil prices by four times, and this resulted in a worldwide recession.] In June 1967 the Labour government devalued the currency by 15%. Given what has been said about inflation, this is already an indication that the country's balance of payments problems stemmed from an old and inefficient industry coupled to an inflexible labour market. Successive governments made attempts to control wage-cost-push inflation. They used statutory polices. Retrospectively, we see these to be misguided, since market forces cannot be “bucked”, but they are indications that at the time the threat of cost-push inflation was recognised. However, in 1972 the Barber budget reflated the economy, and must have given an impetus to inflation. The Yon Kippur War and the resultant quadrupling of the oil price, at a time when demand for it was inelastic, was a disaster for the British economy at the time. There is little doubt that the rise in oil prices helped to push up UK inflation to 16% in 1974, 25% in 1979, only coming under control with a fall to 15% in 1980. The Labour government introduced monetarist policy, which the Thatcher government of 1979 continued. The main policy instrument was interest rates, which were increased by the Thatcher government to 17%. However, there is the question as to whether the government engineered an over-deep recession primarily through their unwillingness to influence the exchange rate. The high interest rates created high demand for sterling pushing up the exchange rate, and thus making British manufactures uncompetitive abroad. This process was exacerbated by the arrival of North Sea Oil. Output of UK oil started in the late 1970s and reached a peak in 1984. The demand for oil contributed to the demand for sterling, and hence accelerated the decline in manufacturing.

|

|

|

The increase in unemployment during the 1979-81 recession and thereafter can be accounted for as follows: (1) old and inefficient capital stock making for a uncompetitive manufacturing industry; (2) downward pressure on real wages for semi-skilled labour on the global market; (3) strong trade unions committed to a policy of increasing real wages and prepared to use industrial action to achieve their objectives; (4) build-up of inflationary pressures in the economy, stemming from government demand management policies; (5) the need for restructuring of the economy in response to global pressures and membership of the EEC; (6) the build up of long-term unemployment as the recession bit.

|

|

|

The Thatcher government began the changes that made Britain's position in the late 1990s more encouraging; though the price that has had to be paid for this is quite considerable. Central to the supply side measures introduced was reform of the labour market, which in practice meant the introduction trade union legislation to reduce the power of the unions to resist downward pressures on real wages.

|

|

|

At the same time, the recession necessarily weeded out the weak and failing manufacturing industries, and forced those that survived to adopt a different culture. The evidence is now that British industry is now quite competitive, although it has not yet reached the levels of productivity of their Japanese and German rivals.

|

|

|

The evidence is also that Britain now has a very flexible labour market, and is in comparison to mainland Europe a low wage economy. Non-wage costs are also to the lower end of the European spectrum, and this makes Britain very attractive to inward investment. The revival of the British car industry was largely attributable to this process.

|

|

Common Agricultural Policy |

|

The European Economic Community (EEC) was formed by the Treaty of Rome in 1958. This created a customs union between the six founder states - Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands . They introduced the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) apparently to protect farming communities within the customs union. The aims of the Common Agricultural Policy were to (1) increase productivity; (2) raise incomes for farmers; (3) stabilise markets for farm produce; (4) ensure the continuity of supply of farm products; (5) ensure reasonable prices. [The EEC evolved into the European Union (EU) as a result of theTreaty of Maastricht (1991)]

|

|

|

In order to achieve these aims the EEC introduced a price intervention system. This requires the European Commission to purchase farm products at above the world price. It effectively created a customs barrier around the European Union. It gave rise to the formation of substantial “food mountains” as European farmers overproduced.

|

|

|

The common agricultural policy is an example of a system of preserving a structural rigidity in the labour market. In 1958, when the EEC was formed, 20% of its population were employed in agriculture, and it was Europe's largest industry. This compares with less than 2% of the population in agriculture in Britain. European agriculture is inefficient in comparison to agriculture in the USA and Canada. If there was no Common Agricultural Policy, and hence no tariff barrier around Europe, European farmers would be forced off the land. There would be high unemployment of a structural kind. The farmers would migrate to cities and become industrial workers; some would change their skills and enter markets for skilled labour. The result would be a decline in the proportion of the population employed on the land. The Common Agricultural Policy has forced this process to be much slower. Migration is still occurring but at a very much slower rate.

|

|

|

In effect the Common Agricultural Policy is a subsidy paid by European consumers to European farmers. European consumers eat less and pay a higher price for their food. It is effectively a food tax, transferring income from food consumers to farmers.

|

|

|

However, that does not mean that the policy is a mistake. The wholescale migration of farmers would have caused a degree of political unrest that Europe (still in the wake of the upheavals of the Second World War) might not have been able to sustain. It is the price that Europe has had to pay for stability.

|

|