|

Efficiency and Shareholder Ratios |

Efficiency ratios |

|

The company depends on the efficiency with which it deals with a number of processes. Trends in the efficiency of the company can be determined by analysis of the accounts. Some of the key ratio used in the monitoring and analysis of ratios are:

|

|

|

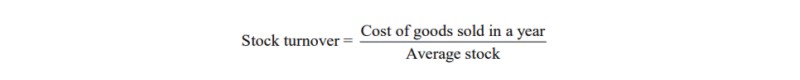

Stock turnover

|

|

|

|

This tells us how many times the average stock level is sold during a twelve month period. A rise in the turnover ratio is an indicator of increased efficiency or an indicated of increased activity.

|

|

|

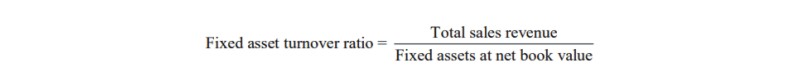

Use of fixed assets

|

|

|

|

This tells us how effectively the assets of the company are being used. A rise in the fixed asset turnover ratio indicates that for each $1 of asset value more sales are being generated.

|

|

|

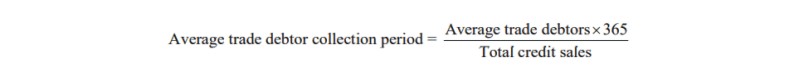

Debtor collection period

|

|

|

|

This indicates the average time taken to collect trade debts. In other words, a reducing period of time is an indicator of increasing efficiency.

|

|

|

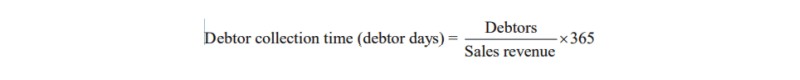

Debtors

|

|

|

|

An increase in the debtor days indicates that there is growing delay in the receipt of cash. Debtor and collection days should be studied together.

|

|

|

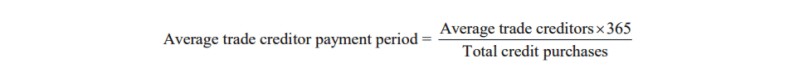

Trade creditor payments

|

|

|

|

Looks at the speed with which the company pays its bills. A falling trade creditor payment period indicates that the company is paying its bills faster.

|

|

Shareholder Ratios |

| Dividend Yield and Earnings per Share |

|

|

Two important ratios that are of primary interest to investorst are dividend yield and earnings per share. Declared dividend yield is the rate of interest paid on the nominal value of the share. If you paid more than the nominal value for the share, then your actual yield is less.

|

|

|

We have already examined the relationship between investors and the corporate life-cycle. Businesses following this cycle require investment, they grow, reap profits, decline and go into liquidation. Ideally, the investor wants to be in at the beginning. To pay $1 for a share with a nominal value of $1. Initially, the company will make losses, but the share price should not fall, provided the company is on track to make profits in the future. Once the product and the company matures, then the rate of return may be as high as 20%, 30%, 40% or more.

|

|

|

In a company following the corporate life-cycle the total dividend paid out should eventually be equal to the total profits made, since there is no further need for the profits, once the investment is made, and the company is expected to eventually go into decline. During the period of decline, when there is asset stripping, the dividend paid out may exceed the profits being made, as investors are not also being returned part of the money they originally invested. The fixed assets are being liquidated, and returned as cash through the dividends to the investors.

|

|

|

So dividends are an indicator of the value of an investment. But in practice, dividend ratios take second place to another investment ratio — earnings per share.

|

|

|

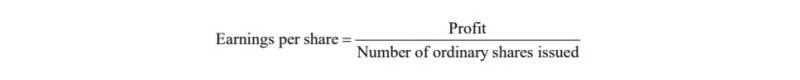

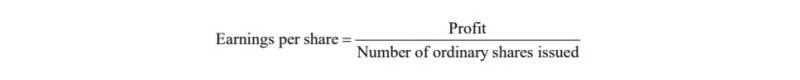

Earnings per share

|

|

|

|

|

Here profit means profit after tax and interest, but before dividends are distributed.

|

|

|

The main point here is that companies do not distribute all their profits, but retain profits in order to reinvest them as a means of internal growth.

|

|

|

In the corporate life-cycle this would occur during the early stages of the company's life, when the product has been launched, and is just beginning to make profit, but the company needs to grow in order to produce more.

|

|

|

There is a second point here too. In fact, most companies do not follow the corporate life-cycle. This is because they do not produce just one product which follows just a single product life-cycle. Even individual products can enjoy a period of rejuvenation or extension. Some products are very durable in their appeal to consumers — for example, public school education in England. More importantly, companies endeavour to extend their own life-time by developing new products. In that case, a company could be proceeding through several corporate life-cycles simultaneously, and the overall company profit arises from the adding together of the losses being made in the products undergoing development and the profits from those at their maturity stage.

|

|

|

The net effect of all of this is that at no time in most mature companies are all the profits of the company ever distributed to the shareholders in the form of dividends. Profits are always retained as a source of internal growth, ultimately in order to extend the life-time of the company, and in that way increase profits for the shareholder in the even longer-run.

|

|

|

Once an investor has bought a share, her wealth is increased each year by the total profit made by the company. That increase in her wealth is divided into two parts.

|

|

| 1 | | Cash distributed to her in the form of a dividend. |

| 2 | | Increased investment in the company, in the form of retained profits converted into new fixed assets. |

|

|

|

This is the distinction between liquid and fixed assets again. The investor gains an increase in her fixed assets, and an increase in her liquid assets at the same time.

|

|

|

But what if the investors does not wish to increase her fixed assets, but would rather have all her earnings converted into cash?

|

|

|

This is where the stock market comes in. The stock market makes it possible for such an investor to sell some or all of her shares in the company to another investor. In order to have her money now the investor with the shares must sell at a price that attracts the other investor to have the money later. This is a price that reflects the time-preference of money, the inflation premium and the risk premium over a long period of time. So, it is the earnings per share that attracts other investors to buy.

|

|

|

Investors are rewarded for their investment in two ways:

|

|

| 1 | | Through the dividend paid |

| 2 | | Through the increase in market share price |

The market share price is ultimately related to the profitability of the company, and is measured through earnings per share.

|

|

|

Questions

|

|

|

1. What is the distinction between dividend and earnings per share?

|

|

|

Companies make profits, but only part of the profits are distributed in the form of dividends. The other part is retained by the company for reinvestment. The shareholder benefits both from the investment and from the dividend. The earnings per share is a measure of the total return on the share, not just the dividend.

|

|

|

2. Why do most companies seek to avoid the corporate life-cycle?

|

|

|

Most companies do not want to go completely out of business. Therefore, they seek to maintain demand for existing products and create demand for new ones.

|

|

|

3. Why do people buy shares in companies that are already mature?

|

|

|

The term “mature” here means that the company's product is in the maturity phase of the product life cycle. People have different motives for investing in the stock market. Some people want to make rapid profits and are very attracted to speculation. Other people want a stable, secure income with little risk. Such people are attracted to “blue chip” companies with products that are mature and virtually guaranteed to continue to yield steady profits for the foreseeable future.

|

|

|

4. Is investing on the stock market a long or short-term investment?

|

|

|

Of course, it is both. However, analysis of trends in the stock market indicate that it is vulnerable to short-term fluctuations. Also there is a cost in purchasing and selling shares. The stock market makes bigger yields over the long-run. Therefore, someone interested in investing in the stock market should consider it principally a medium to long-term investment.

|

|

|

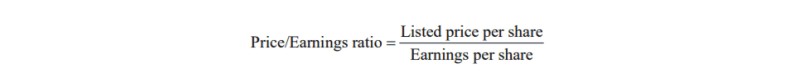

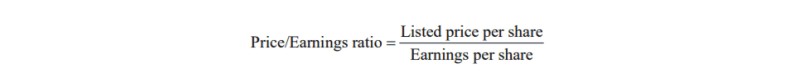

Price/Earnings Ratio |

|

|

We have already seen that investors are rewarded for their investment in two ways

|

|

| 1 | | Through the dividend paid |

| 2 | | Through the increase in market share price |

|

|

|

The market price is ultimately related to the profitability of the company, and is measured through earnings per share.

|

|

|

Suppose the risk involved in every company was the same, and each company produced a fixed rate of return, how would the share-price of one company be related to the share-price in another?

|

|

|

In this instance the ratio of price to earnings in each company should be the same.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This ratio is called the price/earnings ratio.

|

|

|

|

|

The price/earnings ratio gives some clue as to why prices of share fluctuate.

|

|

|

Suppose one company is consistently making more profit than another. In that case, the earnings per share in that company is consistently higher than the earnings per share in the other company. Consequently, the market price of that company should go up, so that, other things being equal, the price/earnings ratio is the same for all companies.

|

|

|

In practice, this is not the case, because different companies are at different stages of the corporate life-cycle.

|

|

|

Analysis of Return on Investment |

|

|

Investors want to know

|

|

|

How the earnings they are making with a share compare with the earnings or rate of interest they would make with other investments.

|

|

| 1 | | How the earnings they are making with a share compare with the earnings or rate of interest they would make with other investments. |

| 2 | | Whether the company was retaining profits for a good reason — for future investment. In that case, they would want to know how the profit the company was making compared to the profit other companies were making. |

| 3 | | How the value of the earnings per share in one company compared with the value of the earnings per share in another. |

|

|

|

Three ratios provide numerical indications of answers to these questions.

|

|

|

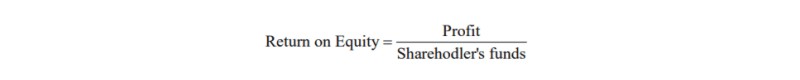

1. Return on Equity

|

|

|

|

|

In this ratio, profit means profit after tax, interest and extraordinary items.

|

|

|

2. Earnings per share

|

|

|

|

|

Here profit is profit after tax and interest but before extraordinary items.

|

|

|

3. Price/Earnings ratio

|

|

|

This ratio shows how the earnings per share in one company compares with the value of the earnings in another.

|

|

|

|