|

Organisational and management structures

|

Organisational structures |

| The aim of any business is to maximize profit. In order to do this there must be division and specialization of labour. This implies that different people come together in order to create a product that has value to consumers. Hence, the activities of different people involved in a business must be coordinated. So there is a need for an organisational structure that brings this coordination about. People in an organization must know:

|

|

| • | | What their activity is and where it fits into the product as a whole. |

| • | | What their roles is, what responsibilities they have and to whom they are answerable. |

|

|

The need to delegate |

Any organizational structure, which implies the combination of activities, is impossible without delegation. It is especially necessary in a large organization to delegate decision-making. The obvious problem is that in opposition to this imperative to delegate is the equally important need to coordinate all activities. Delegation does mean that the manager loses a measure of control. It is important that the overall shape of the organization is maintained. A great deal of management theory is focused on this issue — for example, the concept of a mission statement for the company so that everyone knows where the company as a whole is heading and can take responsible decisions accordingly.

Delegation also means empowerment — it means that subordinates have a more enriching work experience.

|

|

Structures |

| It is usual to distinguish between three types of role within an organization, and hence authority. |

|

| • | | Line. This is based on the analogy with an army. Each manager has authority over his subordinates. |

| • | | Staff. This comprises a group of advisers who do not have authority to command the general staff, but have the right and duty to advise managers. |

| • | | Companies have a choice between two types of organizational structure. (1) line only, and (2) line and staff. The line and staff organization obviously arises when companies recognize the need for an advisory body. Clearly, since business is a dynamic process, there must be changes and innovations. A company without staff may be uninventive. However, the obvious problem of the line and staff structure is that there can be clashes between line managers and staff advisors. |

|

|

Span of Control |

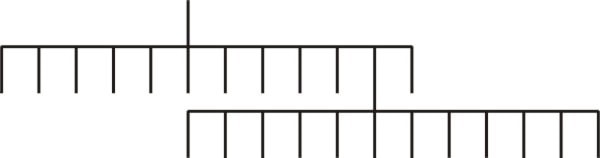

| Span of control is the term for the number of subordinate employees directly accountable to a manager. The larger the number of employees a manager controls the wider is his span of control. |

|

| • | | Narrow span. The manager controls six or fewer employees. There is close supervision of the employees, tight control and fast communication. However, the supervision can be too close, the narrow span means that there are many levels of management, resulting in a possibly excessive distance between the top and the bottom of an organisation. |

| • | | Wide span. The manager controls more than six employees. Managers are forced to delegate work, and tasks may be less closely supervised. There are possible problems with the overloading of work and with loss of control. However, there are fewer levels of management. |

|

|

The need for a line structure |

| Span of control means the number of people directly answerable to a manager. If a manager has to control too many subordinates then supervision becomes ineffective. Span of control should vary with level. Typically 4 to 8 for upper levels of organization, and 8 to 15 for lower levels are recommended. Obviously, this depends on the nature of the task. Routine tasks require less management time to supervise. It is because of span of control that a line structure has to develop. A company with 500 staff cannot have 1 manager and 500 subordinates. There must be a line of authority.

|

|

Flat or Tall? |

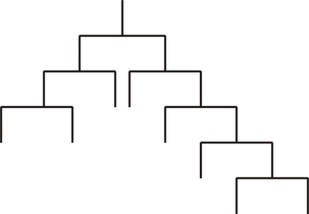

| Hence, companies must have a line structure, but companies do have a choice between flat and tall organizational structures. (1) In a tall structure each manager has a small span of control and there are many ranks; (2) in a flat structure, span-of-control is greater and there are fewer levels of management.

|

|

|

|

|

| Tall structure |

|

Flat structure |

|

|

| There is a recent development in favour of flatter structures. It is argued that this kind of structure is leaner and fitter, more flexible and better able to cope with changes in the external business environment. |

|

| Tall structures are more “military” in style, and might have the advantages of a well-run army. But being in a business is not quite like being in an army and people do not always accept the same level of authority and coordination; they can resent the military style of administration. There has recently been a movement towards “flatter” organizations which can be more democratic and innovative. |

|

| Alfred Sloan invented the concept of the decentralized, multi-visional corporation of today. He instituted “federal decentralization” at General Motors. |

|

Departmentalisation |

| Business organisations are generally divided into specific departments — personnel, purchasing, production, sales, finance, distribution — are examples. None of these departments can function properly without the other departments. |

|

| In large companies there must be departmentalisation. This means, activities must be coordinated by organizing them into departments. A company obviously faces the problem of how best to organize its departments. The solution must depend on each company, its market and also culture. Any departmental organization means that there can be conflict between departments and a loss of communication. It also means that the company loses the benefit of organizing one way by organizing in another. Departments can be orgainised by: |

|

| • | | function — for example, personnel, production, marketing; |

| • | | product |

| • | | territory (geographical region) |

| • | | market segment or customer |

| • | | time — for example, by shift |

| • | | numbers — that is, to produce teams of a specific size |

| • | | equipment |

|

|

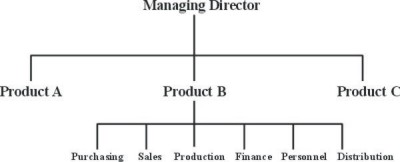

| However, the usual choice facing a company is whether to organize by function, or by product. |

|

Organisation by function or product? |

| The functional approach is used in large organisations. Another alternative is to organise the company according to products. That is, the company is divided into separate organisations, each of which is responsible for a separate product. This is a product approach to organisation. In this case each division within the company is a profit as well as a cost centre. |

|

|

|

|

| | |

| Functional approach |

|

Product approach |

|

|

| Only large companies can effectively employ a product approach to organisation, and the functional approach is suitable for small companies producing a limited range of products in conditions of relative stability. |

|

Matrix structure |

| Different structures can be combined together. When one has two parallel organizational structures this is called a matrix structure. The idea is to combine the advantages of two structures, but this has the obvious disadvantage of being harder to coordinate and introducing more potential conflict. |

|

| In the past most large companies were centralized — that is, involved structures in which decisions were taken at the centre or upper levels of organization. Just as there has been a move to flatter organizations, so there has been a move to decentralized ones. |

|

Centralised/Decentralised |

| A centralised company is one where the decisions are taken at the centre of the company; a decentralised company is one where the decision-making is delegated to lower levels of management within the organisation. |

|

|

|

| Modern theorists tend to argue in terms of adopting a contingency approach. What this means is using the approach that is most appropriate in the circumstances, as we have already seen that both a wide span and a narrow span have their attendant advantages and disadvantages. |

|

| Alfred Chandler argues that structures follows strategy in organizations. Strategy is the determination of long-term goals and objectives, courses of action and allocation of resources, and structure is the way the organization is put together to administer the strategy, with all the hierarchies and lines of authority that the strategy implies. |

|

Informal/formal organisations |

| Within any company there are two types of organisation — the formal structure and the informal structure. Both effect the organisation and relationships between staff.

|

|

| The formal organisation refers to the formal relationships of authority and subordination within a company. The primary focus of the formal organisation is the position the employee/manager holds. Power is delegated from the top levels of the management down the organisation. Each position has rules governing what can and cannot be done. There are rewards and penalties for complying with these rules and performing duties well. |

|

| The informal organisation refers to the network of personal and social relations that develop spontaneously between people associated with each other. The primary focus of the informal organisation is the employee as an individual person. Power is derived from membership of informal groups within the organisation. The conduct of individuals within these groups is governed by norms — that is, social rules of behaviour. When individuals break these norms, other members of the group impose sanctions on them. |

|

| Clearly, the informal structure can be either beneficial or detrimental to the functioning of the company or both. |

|

| People who work in an organization are only human and their effectiveness may depend on their personal relations with those around them. An obvious illustration is that if a manager is aware of a personality clash between employees he must respond. |

|

| Joseph Juran devised a structured concept known as Company-Wide Quality Management. He saw greater empowerment of the workforce as the key to achieving quality through self-organization and self-supervision. He thought that quality is indissolubly linked with human relations and teamwork. He praised the Japanese use of quality circles for their effect on human relations in the workplace. |

|

| Elliot Jacques developed a theory of measuring the value of work by the time span of “discretion” that elapses before the decisions are monitored. He noted that a confusion of roles or unclear boundaries of responsibility lead to frustration and insecurity, and to a tendency in management to avoid authority and accountability. A worker may see his “real” boss — the one he feels he has a chance of getting a decision about himself — as someone quite different from the person next in line up the hierarchy. |

|

Weber and the issue of Authority |

| Businesses generally require one person to exercise authority over another. Weber”s classified authority in terms of (1) authority derived from tradition — that is the authority of a tribal chief; (2) authority derived from charisma — the authority of a dictator or saint; and (3) authority derived from position on a “rational legal basis”. |

|

| The last category applies to the classical view of a business organisation in which authority originates high up in the organisation and is passed down. |

|

| Weber was a sociologist who had a high respect for bureaucracy as a form of business and social organization and he believed that authority should be vested purely in position and not in character. Whilst every business involves elements of bureaucracy, it is now generally recognized that a purely bureaucratic structure for a company and a bureaucratic culture is a potentially damaging form of organization. This is because business is a dynamic, changing activity and only those companies that constantly adapt to new environments will survive and prosper. From the motivational point-of-view people may not obey a manager when his authority rests purely in his position. Managers are generally appointed on merit, and must earn respect, hence in addition to authority based on position there must be authority based on respect. |

|

| The modern view of authority is the acceptance view. Acceptance of authority is necessary if the communication is to carry authority. The authority of the superior is more acceptable if he or she is respected. Combining the classical and modern view we can state that authority is distinguished by three characteristics: |

|

| 1. | | It is vested in positions, not people |

| 2. | | It is accepted by subordinates |

| 3. | | It flows down the vertical hierarchy |

|

|

| If authority means the right to make a decision, then responsibility is the duty to perform a task or activity that has been assigned. When a superior assigns a task to a subordinate the latter is given the authority (or right) to carry out the task, but he or she is also given the responsibility (duty) of carrying out the task.

|

|

| Chester Barnard identified “organizational man” — the most single contribution required of the executive is loyalty — which means domination by the organization of his personality. Business organizations should be driven by the cooperation of individuals working to a common purpose rather than by authority. Authority in an organization only exists insofar as the people in that organization are willing to accept it. Good managers motivate employees towards the organization”s goals. The good manager is a value shaper. The good manager is not authoritarian. |

|

|

|

|

|