|

The Era of Lenin — The Soviet Union 1917 to 1924 |

Conclusion of the 'October' Revolution |

|

Lenin, together with Stalin as People's Commissar for Nationalities, expected that the revolution would spread throughout Europe and that a pan-European socialist state would ensue. Thus, their Declaration of Rights of the People's of Russia of 3rd November abolished all national and ethnic privileges and called for a 'voluntary and honourable union'. They also confirmed the right of each nation to secede.

|

|

|

On 7th December, Sovnarkom, that is the Council of People's Commissars, which was at this time the self-appointed government of Russia, agreed to the formation of a force, that is to say a political police, to deal with any threat of counter-revolution — the Extraordinary Commission or Cheka. There was no formal delimitation to the powers of this organ of repression. The chairman of the commission was Felix Dzierzynski. The first victims of this body were criminals, and politicians were not its initial targets.

|

|

|

In mid-December the Left Social Revolutionaries agreed to support the Bolsheviks bringing about a two-party coalition.

|

|

|

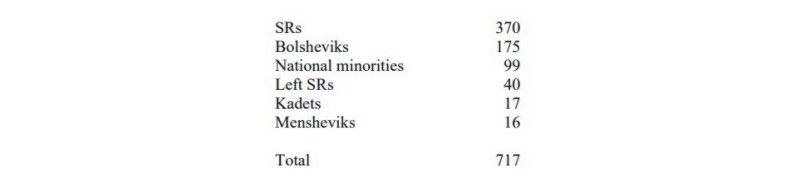

Lenin immediately wished to dispense with the elections for a Constituent Assembly, but Bolshevik propaganda committed him to going ahead with them. Polling arrangements were confirmed in November. However, the Bolsheviks gained only about 25% of the popular vote, with the Social Revolutionaries gaining 37%.

|

|

|

|

|

Composition of the Constituent Assembly

|

|

|

The Constituent Assembly met on 5th January 1918 at the Tauride Palace. Social Revolutionary leader Viktor Chernov denounced Bolshevism in his speech and affirmed his party's commitment to parliamentary democracy. At this point the anarchist Zheleznyakov announced that 'The guard is tired!' The doors of the Constituent Assembly were closed (for ever) and a demonstration in support of it was fired upon by troops loyal to Sovnarkom.

|

|

|

Lenin did not believe in democracy - he regarded it as 'bourgeois'. It was the duty of the Bolshevik Party to guide the proletariat towards fulfilment; they had the right to expect the obedience of the Proletariat. This is the theory of democratic centralism, and Lenin used it to justify disregarding election results that did not mandate his policy. Lenin stated that “To hand over power to the Constituent Assembly would again be compromising with the malignant bourgeoisie.” He justified his action by defending it as giving power to the Soviets.

|

|

|

There was more opposition elsewhere in Russia, most notably in the Ukraine, where armed conflict took place in late January 1918 and Kiev was occupied by troops loyal to Sovnarkom.

|

|

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk |

|

The Bolsheviks entered into negotiations with the Germans and Austrians. These were held at Brest-Litovsk. Lenin ordered the demobilisation of Russian armies. Trotski successfully spun out the negotiations. However, by late January 1918 the Central Powers issued an ultimatum calling for a separate peace or Russia would be overrun. Lenin advocated acceptance of the humiliating peace terms. On 8th January he gave his “Theses on a Separate and Annexionist Peace” to the Third Congress of Soviets, but it was rejected by 63 votes to 15. However, Lenin fought for agreement, and secured Trotski's private consent, and the support in the Central Committee of Sverdlov, Stalin, Kamenev and Zinoviev. The Germans began their advance, taking Dvinsk on 18th February, whereat the Central Committee agreed to Lenin's policy. Trotski vacillated when the Germans increased their demands. Lenin furiously campaigned for acceptance of the peace treaty. “These terms must be signed. If you do not sign them, you are signing the death warrant for Soviet power within three weeks!”

|

|

|

Lenin accepted that “The Russian Revolution must sign the peace to obtain a breathing space to recuperate for the struggle.” There was a division in the central committee over whether to accept the treaty. Trotsky, Stalin and Zinoviev voted with Lenin; Bukharin, Kamenev and Dzershinsky voted against. Trotsky and Lenin believed in an international revolution; the others were more patriotic. Lenin won the day by insisting on party loyalty. The peace treaty also caused a split in the Sovnarkom. Left Communists under Bukharin resigned; so did the Left Social Revolutionaries.

|

|

|

The continuing threat to Petrograd caused Lenin to move the capital to Moscow on 10th March, as a precaution in case the Germans decided to occupy the whole Baltic region. The treaty meant that Russia lost half its grain, coal, iron and human population!

|

|

|

An economic crisis loomed. The harvest of 1917 was 13% below the pre-war average, but was still 13.3 million metric tons short of the country's needs. Peasants with surpluses refused to sell them.

|

|

Consolidation of Power |

|

The popularity of the Bolsheviks rose during the last months of 1917, but by 1918 it was falling. The elections for the Constituent Assembly showed that the Russian people wanted a socialist government, but not a single-party state.

|

|

|

The Bolsheviks were also in the main only supported by Russian people. Their support derived from Russian cities or cities outside Russia where there were many ethnic Russian workers. Only in the Baltic states, where hatred of Germans was greater than fear of Russians, did the Bolsheviks gain any non-Russian support. So from the start the Bolshevik dictatorship was based on the practical reality of ethnic divides. The empire was also fragmenting. Turkish support enabled independent states to be established in Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia. The communists were pushed out of Baku and had no control over the Transcaucaus whatsoever.

|

|

|

Lenin instituted a policy of federation. On 5th December he published a Manifesto to the Ukrainian People calling for a federal government. His Declaration of the Rights of the Toiling and Exploited People called for a “free union of nations as a federation of Soviet republics”, and he proclaimed the formation of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic (RSFSR) in late January, after the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly.

|

|

|

The exact term in Russian for 'Russian' emphasised that all nations within the geographical area of the former empire were to be treated on an equal footing. The intention was that ethnic Russians would not enjoy a privileged position within the new nation.

|

|

|

Whatever they wanted in theory to achieve, by mid 1918 the Bolsheviks were trapped in a Russian enclave. In order to break out of this enclave the Red Army would need to impose its will on the borderlands.

|

|

|

The Bolsheviks gained most support from the Decree on Land. This was most effective in the central areas, where peasants felt no inhibition in moving against the historic landowners. Elsewhere, there were some inhibitions and less redistribution of land took place — for example, in regions close to the Eastern front or in central Asia.

|

|

|

The soldiers of the armed forces also benefited from the Bolshevik revolution. Many conscripts returned to their peasant villages in order to partake of the general carve up of land. For those that remained there was increased internal democracy in the forces, with election of officers not being uncommon. Such units often became supporters of the revolution and fought in the early campaigns to consolidate it. They received good rations. The units with high morale and good leadership were nutured by the Bolsheviks. Most such regiments were non-Russian. The Latvian riflemen were particularly important.

|

|

|

Workers also benefited. They seized the large houses of the rich and turned them into flats. The Bolshevik leadership also prioritised food supplies to the industrial labour force. The workforce became less militant. Fearing for their security, they sought to keep their workshops open, and many workshop committees nationalised the factories they worked in as a means to this end. Thus nationalisation took place at a pace faster than that actually advocated by official party policy. Anyone who hired labour for profit was deprived of voting rights.

|

|

|

Although peasants gained from the Decree on Land, this did not induce them to offer idealistic support for the regime. In other words, peasants were not more willing to send food-supplies to the cities simply because they had benefited from the revolution. So a food-supplies crisis developed. There was also no increase in output as a result of the land redistribution. Peasants did not overnight adopt improved farming techniques or share farming implements.

|

|

|

The Bolsheviks were opposed by the Orthodox Church, which elected its first Patriarch for 200 years in November 1917. This was the Moscow bishop, Tikhon. The Orthodox Church was alarmed at the atheistic philosophy of the Bolsheviks.

|

|

|

The Bolsheviks were keen to enlist the support of the intelligentsia, but most poets, painters, musicians and teachers were not sympathetic to the revolution. Nonetheless, teachers were the most supportive of this group; they also wanted universal literacy and numeracy and would have to cooperate if they wanted to be paid.

|

|

|

Some artists did respond positively to the offer of material inducements. For example, opera singer Fedr Shalyapin, painter Marc Chagall and poets Sergei Yesenin and Alexander Bok gave tacit support to the regime. But intellectuals were slowly cajoled into giving support for the regime by the realities of hunger.

|

|

|

In industry Lenin advocated that small and medium-sized enterprises should be nationalised and combined into single large syndicates — one for each industry. He wanted these to be run as vast capitalist enterprises. He accepted the need for capitalism in the transition phase. Once capitalism had served its purpose it would be dispensed with. Lenin called this form of mixed economy, 'state capitalism'. One example of his commitment to this policy occurred in April 1918 when he advocated a joint state-capitalist enterprise between the government and a consortium of entrepreneurs led by V.P. Meshcherski.

|

|

|

The Bolsheviks sought to extend their membership among the working classes. People of working-class origin were invited to join the administration. There was positive discrimination in favour of people of working class background. However, there were not enough talented people of this sort to fill all the positions.

|

|

|

However, opposition to the Bolsheviks developed in response to the use of violence by Sovnarkom. The Petrograd metal and textile workers, former supporters of the Bolsheviks, led the outcry by forming an Assembly in Petrograd in spring 1918. But the Bolsheviks responded ruthlessly, using armed troops, for instance, to crush a demonstration by Assembly supporters in the industrial town of Kolpino.

|

|

|

The exercise of arbitrary power was increasing, not decreasing. The number of administrators was increasing, and the extent to which the administration intruded into ordinary people's lives was also increasing. The failure of Sovnarkom to attain political and economic objectives was assumed by Lenin to be a sign of a lack of hierarchical supervision, and so, rather than decrease bureaucracy, he tended to increase it, creating new institutions whose function was to supervise others, and more and more paperwork. Citizens were increasingly aware that their rights were not inalienable. Local officials became less cooperative towards Moscow.

|

|

The Civil War 1918 — 20 and the Foreign Interventions |

|

It seems that neither Lenin nor the Central Committee anticipated Civil War, nor did they explicitly prepare for it. Following a successful victory over a group of Cossacks in the Don region in late January 1918, Lenin assumed that the struggle for power was over. The Bolsheviks started building a Red Army from February onwards, but they did so mainly for the purpose of being able to intervene in favour of an uprising in Berlin, which they still expected.

|

|

|

Trotsky created the Red Army and became commissar for war after the signing of the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk. He used many ex-tsarist officers but attached to each one a political commissar. Military orders had to be countersigned by the political commissar. Desertion or disloyalty carried the death sentence. Initially, graded ranks were removed, but Trotsky soon decided to reinstate them. Election of officers was dispensed with. There was forced conscription in some areas. Possible dissidents were conscripted and forced into labour camps. Elite troops were drawn from the workers. The morale of the Red Army was relatively high. Defeated enemy troops were offered the choice of 'join-up or we'll kill you.'

|

|

|

However, in May 1918 the Socialist Revolutionary leadership fed to Samara on the river Volga, where they established a Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly (Komuch). Armed conflict between the two centres was inevitable.

|

|

|

Meanwhile generals Alekseev and Kornilov had escaped to southern Russia and were gathering an army of volunteers. Admiral Kolchak was forming an army in mid-Siberia. General Yudenich was organising in the north-west. These forces became known as the White armies.

|

|

|

The Left Socialist Revolutionaries planned an insurrection against the Bolsheviks. They also organised the assassination of the German ambassador in Moscow, Count Mirbach, on 6th July, when they also took Dzierzynski hostage. Lenin sent his condolences to the Germans and instructed the Latvian Riflemen to arrest all Left Socialist Revolutionaries. The Fifth Congress, sitting at the time, endorsed this policy.

|

|

|

There was also a legion of Czech and Slovak prisoners-of-war being transported along the Trans-Siberian railway. This legion resisted being disarmed, and moved back over the Urals, reaching Samara on the Volga by May. It was persuaded by Komuch to join them. The Czech legion took Kazan on 7th August, 1918. Trotsky organised the Red Army's response, and in September it was recaptured by the Red Army. On 7th October the Red Army overran Samara and the Czech Legion retreated to the Urals, and joined the command of Admiral Kolchak. Kolchak temporarily recognised Komuch as the legitimate government, but on 17th November he had most of its ministers arrested and proclaimed himself 'Supreme Ruler'. The Social Revolutionary party was finished. His forces captured Perm in late December and started to march on Moscow.

|

|

|

Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated on 9th November, and this cancelled the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Lenin encouraged the formation of a German Communist Party and supported Bolsheviks in setting up Soviet republics in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Ukraine.

|

|

|

The Cheka's powers were extended. Left Socialist Revolutionaries were arrested. Lenin, Trotski and Dzierzynski had many opponents killed. The family of the Romanovs were murdered on 17th July at Yekaterinburg. It is unlikely that this occurred without the approval of Lenin and the Central Committee.

|

|

|

There were changes to the government. As the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party was unable to meet regularly, two inner subcommittees were created in January 1919. These were the Politburo, responsible for state policy, and the Orgburo, assisted by a Secretariat, which was responsible for party administration. Power passed from the Sovnarkom (the Council of People's Commisars) to the Politburo. Lenin chaired the Politburo, which became effectively the government cabinet, though not formally recognised as such. The first Politburo comprised Lenin, Trotski, Kamenev and Kretinski. There were personality conflicts between Stalin and Trotski. Stalin sought to undermine Trotski's policy of using former Imperial Army officers in the Red Army and create an opposition to Trotski within the military. Trotski attached political commissars to each high ranking officer, and defended the use of terror in his book Terrorism and Communism published in 1920.

|

|

|

The Red Army defeated Kolchak in April 1919, taking Perm in July and Omsk in November. Kolchak was captured and executed in 1920. General Denikin took over command of the armies led by Generals Alekseev and Kornilov, and advanced into the Ukraine during the summer of 1919. He took Kharkov in June, Kiev and Odessa in August, and Orel in mid-October. However, the Red Army counter-attacked and recaptured Kiev and re-established the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. General Yudenich's attack from Estonia was also repulsed, and by November the Civil War in Russia was over. Siberia and the Ukraine were back under the control of the Reds.

|

|

|

Elsewhere the Civil War brought ethnic conflicts to the fore and in the Transcaucasus Georgians fought against Armenians, Armenians fought Azeris, Georgians fought Abkhazians. Atrocities were committed. After the defeat of the White Armies the Red Armies intervened.

|

|

|

Lenin and Stalin sought to develop the idea of a federation, and aimed to set up autonomous republics wherever Russians were in a minority. They aimed to establish a Tatar-Bashkir Republic but this failed as the two ethnic groups would not cooperate with each other. The Ukraine was proclaimed to be a Soviet Republic, and Soviet republics were established in the Transcaucasus in March 1921 — Belorussia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia became Soviet Republics. The RSFSR was a separate soviet republic and bilateral agreements were established between each republic and the RSFSR. However, bilateral relations between the other republics were expressly disallowed.

|

|

|

However, in practice the entire RSFSR was highly centralized and that the other Soviet republics were subject to the Politburo.

|

|

|

Nonetheless, the Reds offered non-Russians more than the Whites. Jews, in particular, were terrified of the White's anti-Semitic bias. Both Reds and Whites committed atrocities. Most notably, the Reds often butchered religious leaders, both Christian and Muslim. The Whites, on the other hand, closely identified themselves with Russian imperialism, and hanged trade unionists.

|

|

|

The Bolsheviks won the battle to control the railways, whilst the Whites lacked a coordinated policy. The Reds were concentrated and maintained their communication and supply lines. They also controlled the industrial centres. The Whites were dependent on foreign support which cast the Reds in the role of Russian patriots. Atrocities were committed on both sides, but the Whites certainly did not amass popular support. The Reds were able to play on the fears that the Whites would prevent the peasants keeping the land they had seized. The Reds had much more conviction and Trotsky succeeded in creating a formidable army. The Whites lacked creditable leaders.

|

|

|

The mood of the foreign powers also swung against intervention, and in 1920 the Supreme Allied Council lifted the economic blockade against the RSFSR, thus leaving the Whites without allies.

|

|

|

The Bolsheviks in general had no intention of holding free elections. They had come to accept one-party dictatorship and the use of terror as a way of life. However, there was some opposition to these policies. In 1919 there was a group of Democratic Centralists arguing that power was concentrated in too few hands. A group called the Worker's Opposition emerged in 1920 arguing that workers' aspirations had not been fulfilled. However, both these groups still endorsed the policy of a one-party state and represented very small numbers of people.

|

|

|

There also emerged the phenomenon of party cleansing — or the purge (chistka). The first purge of May 1918 was not violent and the aim was to remove criminals from the party — by mid 1919 party membership was halved to 150,000. The Central Control Commission was established in 1920 to eliminate abuses in the party.

|

|

|

There was resistance to control. Lower ranks were ill-disciplined, and there may have been up to a million deserters by the end of 1919. Food supplies were disrupted, and disease and malnutrition resulted in 8 million deaths in the period 1918-20. There were mutinies in army garrisons. There were peasant rebellions, 344 by mid-1919 according to official figures. In response the Bolsheviks intensified the repression.

|

|

|

The Poles invaded the Ukraine in 1920, and took Kiev in May 1920, but they were defeated and pushed back into Poland. The Red Army pushed into Poland in its turn, but were defeated by the Poles at a battle near the river Vistula.

|

|

|

Lenin started to promote policies that led to the establishment of the New Economic Policy. He wanted foreign concessions to be granted to restore the Baku oilfields, and at the Eighth Congress of Soviets in December 1920 he advocated the policy that richer peasants should be rewarded for increased grain production rather than persecuted as kulaks. The Congress rejected this scheme in horror.

|

|

Foreign Interventions |

|

France and Britain had offered the Provisional Government considerable quantities of capital and military aid in order to continue fighting Germany. They cautiously made the same offer to the Bolsheviks. But the Bolsheviks concluded an armistice and fighting ceased in December 1917. After this the allies were worried that war-supplies on loan to Russia would go to Germany. They proposed to intervene in Russia. British, French and US forces took over Murmansk and Archangel. Italy and Japan also intervened. Czechoslovakia, Finland, Lithuania, Poland and Romania all sought territorial independence from Russia. British land forces occupied parts of Southern Russia from 1918. The French also occupied Odessa. In April 1981 the Japanese occupied Vladivostok. The Bolshevik government declared that it would not honour foreign debts. French investors were particularly affected. The French were foremost in urging international intervention.

|

|

|

But there was no cooperation among the allies. The Allies came under pressure to withdraw once Germany collapsed and the armistice was signed in November 1918. In 1918 the ex-tsar and his family were murdered. The US were unwilling to send ground troops. Although US troops were sent to Russia, they were sent to prevent other powers from excessive action. There was no coordinated plan to remove the Bolsheviks and the foreign powers were war-weary. There were threats of mutiny in some French and British units and the campaign did not have the support of trade unionists. In general, foreign forces made only feeble attempts to cooperate with White Russians. However, British warships did support the successful struggle for independence of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Foreign troops were withdrawn and by the end of 1920 all Western forces had left; but the Japanese persisted until 1922. The Bolsheviks were able to present themselves as the patriotic saviours of their country.

|

|

|

It was success in the civil war that encouraged the Bolsheviks to attempt aggressive policies and lead in 1920 to the Red Army attacking Poland, in the expectation taht Polish workers would rise in rebellion. But this did not happen. The Red Army was repulsed and humiliated.

|

|

|

Lenin concluded that an international revolution was not possible. The Bolsheviks became less militant towards other countries and sought to survive by playing one capitalist country off another. Thus Lenin's foreign policy fitted into the traditional mould of fear of Western intervention in Russia and a desire to maintain the integrity of its borders.

|

|

The Terror and the Kronstadt Rising 1921 |

|

On the 30th August, 1918, there was an assassination attempt on Lenin's life, whilst he was addressing workers of the Mikhelson Factory in Moscow. A partially blind woman, Fanya Kaplan, was charged with the attempt, and was executed. This was followed by the Red Terror. Over 1300 prisoners were shot without trial in Petrograd alone. Lenin, whilst recovering at a state sanatorium on the Gorki estate, wrote his pamphlet Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade K. Kautsky, which developed the theory of dictatorship and terror. He instructed Bolshevik leaders in cities and towns around Russia to make examples of potential dissidents, writing to the leaders in Penza in a telegram of 11th August: “Hang no fewer than a hundred well-known kulaks, rich-bags and blood-suckers (and make sure the hanging takes place in full view of the people)”. The aim was to terrorise hostile social groups into submission. Officially 12,733 prisoners were executed by the Checka during 1918-20, but the figure may really be as high as 300,000. Concentration camps were established following decrees of September 1918 and April 1919.

|

|

|

The Bolshevik repression was called The Terror. Lenin had no qualms about the use of terror. He wrote, “coercion is necessary for the transition from capitalism to socialism.” The Cheka took over from the Okrana as the secret police. It was created in December 1917 with Felix Dzerzhinsky as its head. The Cheka created terror. SRs assassinated the German ambassador in July 1918 and killed the Petrograd chairman of the Cheka. These attacks were used as the pretext for the terror. The Cheka made no attempt to abide by legal forms. Party members supported the excesses of the Cheka because they believed the situation was extremely dangerous. Dzerzhinsky believed that only extermination of the 'enemies of the working class' could work.

|

|

|

The terror made the Bolshevks unpopular. There was rebellion in the central Russian province of Tambov. The labour commissar, Shlyapnikov, and Alexandra Killontai led opposition within the party to war communism. In February 1921 Petrograd workers and Kronstadt sailors demonstrated for greater freedom. Political commissars were humiliated. Petrochenko was elected as chairman of a revolutionary committee, which published a manifesto making liberal and democratic demands. Trotsky ordered the Red Army to crush the uprising. There was an artillery bombardment followed by the storming of the Kronstadt base by 60,000 troops. Resistance was fierce. The leaders of the uprising were shot. The Cheka pursued anyone who succeeded in escaping. In response to the rising Lenin decided to introduce his New Economic Policy.

|

|

|

The Central Committee was mainly in agreement about the use of terror. Disagreements were not exactly over principles. For example, Bukharin and Kamenev were opposed to the licence given to the Cheka to execute in secret and without trial, but they were not opposed to the executions provided some form of trial had been held.

|

|

|

The membership of the Bolshevik party rose, from 300,000 in 1917 to 625,000 by early 1921. Most of these members fought in the Red Army.

|

|

Economic Policy |

|

State Capitalism 1917-18

|

|

|

State capitalism was a transition stage following the October Revolution in which the Bolsheviks used existing economic structures. Lenin recognised the need for specialists and the need to pay them higher salaries. Russia faced economic disaster and nearly collapsed as a result of the strain of the war. Capital was reduced, there was uncontrollable inflation, the transport system was crippled, grain supplies were disrupted and the Ukraine had been lost. There was the problem of feeding the population.

|

|

|

In November 1917 the Bolsheviks issued a Decree on Land and a Decree on Worker's Control. The first abolished private ownership of land. It sanctioned what had already happened - the peasants had largely taken possession of their former landlord's land. The Decree on Worker's Control legitimated the workers' takeover of many factories. Most of the takeovers were without government approval and were not always initiated by Bolsheviks. In December 1917 there was the establishment of the Vesenkha, the Supreme Council of the National Economy. It lacked authority at first but did establish a State Commission in 1920 to organise a national grid for electricity; banks and railways were nationalised. The government refused to honour foreign debts.

|

|

|

War Communism 1918 - 21

|

|

|

After summer 1918 Lenin adopted 'war communism' in reaction to the Civil War. With the Cheka (secret police) and Red Army Lenin sought to centralise industry. Political commissars were introduced to workers' committees. In June 1918 there was a Decree on Nationalisation that brought industry under central control within 2 years. Lenin still needed the former managers and specialists. The emphasis was on military production. The factories lacked adequate man-power owing to conscription into the Red Army and population from town to country. However, war communism did not create industrial growth. Compared to 1913 the economy had collapsed.

|

|

|

The Kulaks were the richer peasants and the Bolsheviks did not like them and thought they hoarded grain to benefit from higher prices. To prevent this the government was prepared to use force. Lenin also sought to play off poorer peasants against the kulaks but this didn't work because such rivalries were not common. Hence, coercion was used. On 9th May 1918 the Food-Supplies Dictatorship was proclaimed and armed requisitioning of grain was made general policy. Orders issued in August 1918 by the people's commissar for food sanctioned the use of force. The use of force was brutal and counterproductive, because surpluses were confiscated and peasants only produced what they needed. By 1921 there was a national famine. The harvests of 1920 and 1921 were half those of 1913. Relief came mainly from the USA organised by the American Relief Association (ARA), but during the Civil War about 10 million died of which 5 million were due to starvation.

|

|

|

The Food-Supplies Dictatorship established grain quotas for each district. In practice grain was expropriated indiscriminately, and many peasant households starved. In June 1918 Lenin attempted to establish village committees of the poor (kombedy) which were invited to report on richer peasants who were hording grain in return for a hand-out, but kombedy was resented by all peasants and did not succeed in its intended effect. It was abolished by Lenin in December. The state procurement of grain increased fourfold between 1917/18 and 1918/19. Villages tried to cut themselves off from towns and to hoard their supplies.

|

|

|

The black market was essential to the economy. Money was devalued to 0.006% of its pre-war value by 1921. Industry had collapsed; for example, large-scale enterprises in 1921 produced only 20% of the 1913 output. The government sought to maintain key armaments and textile factories. By 1919 all large factories and mines had been nationalised.

|

|

|

Within the party there was debate about the shape of economic policy. Left Bolsheviks, for example, Bukharin and Preobrazhensky, wanted war communism to continue, and Lenin favoured it. But the failure of the policy to revive the economy and anti-Bolshevik uprisings in 1920-1 made him change his course and he announced in March 1921 the New Economic Policy (NEP) at the 10th Party Conference.

|

|

|

The New Economic Policy

|

|

|

Lenin told the conference that “there must be a certain amount of freedom for the small private proprietor; and ... commodities and products must be provided.” The famine in 1921 convinced delegates that Lenin was right. State requisitioning was abandoned and a market economy reintroduced. Lenin saw this as only a brief and limited move towards capitalism. The NEP also allowed for small-scale industrial manufacture to be privately owned. By 1922 it was apparent that there would be no international proletarian revolution. Thus the Russians would have to build socialism in one country.

|

|

|

But Trotsky and Preobrzhensky were among Left Bolsheviks that preferred the coercive methods of communism. There was thus a considerable split within the party and only Lenin's authority prevented it from developing into something worse. Thus the 10th Party Congress gave massive support to Lenin's proposal 'On Party Unity' which outlawed factionalism within the Party and also made all other parties illegal. Thus Russia became formally a one party state, which strengthened Lenin in his claim that the NEP represented no weakening of communist idealism. In fact, Bukharin dropped his opposition to the policy, and gave it strong support. Bukharin became Lenin's closest adviser in the last two years of Lenin's life - Lenin suffered a series of strokes and died in January 1924. Bukharin wrote for Lenin two justifications of the NEP - On Co-operation and Better Fewer, But Better.

|

|

|

Statistics show a steady improvement in output from 1921 to 1925. The grain harvest in 1921 was 37.6 million tons, in 1925 it was 72.5%. Coal output rose from 8.9 million tons to 18.1 million tons in 1925. Average monthly wages of urban workers rose from 10.2 roubles in 1921 to 25.2 roubles in 1925. Agriculture and trade were largely privatised, but industry remained largely state controlled.

|

|

|

With Lenin's illness removing him from active politics, divisions within the Party grew. Trotsky refused to serve on the 'Scissors Committee' and instead became spokesman for opponents of the government's policy - a group known as 'the Platform of 46' after 46 party members that signed a letter openly critical of the government's economic plan. [This committee was convened to discuss the problem of the terms of trade between the countryside (villages) and towns. In the early parts of 1918 trade favoured the villages, although the famine prevented villages from taking advantage of this. However, by 1923 the situation had reversed, with villagers having to pay relatively high prices for manufactured goods of the towns. Hence the term “scissors” since a graph of the relative prices of industrial and agricultural goods during this period would look like two blades of a pair of scissors.] The Vesenkha (that is the “Supreme Council of National Economy” by this time superceded in its functions by another committee called Gosplan, the “State Planning Commision”) had failed to provide a coherent national strategy for the economy. But after October 1923 industrial prices started to fall and the blades of the scissors started to close. But there was still a lack of economic planning and the party was still split ideologically over the New Economic Policy, thus providing the framework for the power struggle that would ensue on Lenin's death.

|

|