|

Introduction to Virtue Ethics |

I |

|

Aristotle is also the originator of the approach to ethics known as “virtue ethics”. However, this theory cannot be separated from Natural Law theory and the function argument on which that is based. This is because in The Nicomachean Ethics Aristotle tells us that

|

|

Happiness = virtuous action taken over a complete lifetime

Virtue = activity performed in accordance with a rational principle.

|

|

|

In other words, you become happy by leading a virtuous life, and you lead a virtuous life by leading the life of reason — maximising reason in all your doings. Since in the function argument Aristotle maintains

|

|

|

The function (form, purpose) of man = to lead the life of reason

|

|

|

then it follows that

|

|

|

The virtuous man performs his function well.

|

|

|

So virtue ethics is based on natural law theory, albeit it without the modern applications of that theory to such matters as sexual morality, which Aristotle would not recognise as an issue.

|

|

II |

|

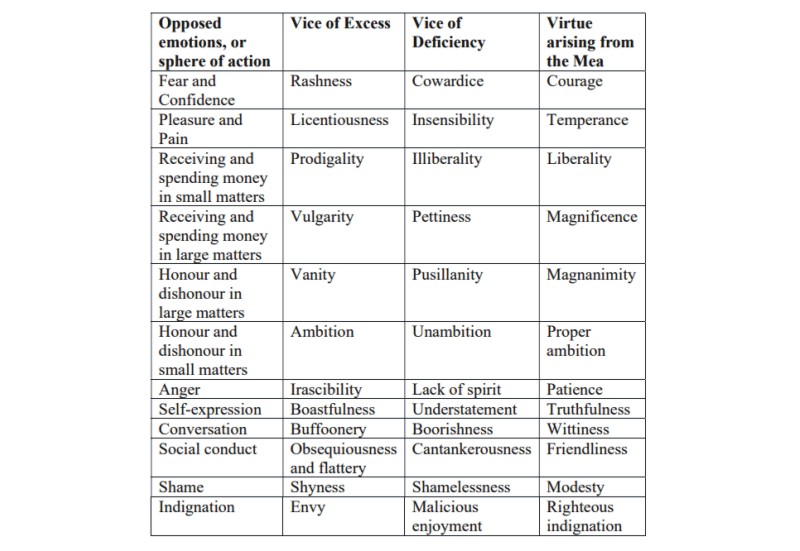

Aristotle's concept of the life of practical virtue is encompassed by his “Doctrine of the Mean”

|

|

|

|

|

|

The purpose of the Doctrine of the Mean is to show how reason can be maximised in a life of practical virtue by using it to even out the effects of conflicting emotions.

|

|

|

Emotions tend to imbalance you — and this leads you into vicious conduct. Using our reason we can prevent this destabilising effect of emotion. [For example, “In the matter of giving and taking money, moderation is liberality, excess and deficiency are prodigality. Both vices exceed and fall short in giving and taking in contrary ways; the prodigal exceeds in spending, but falls short in taking; while the illiberal man exceeds in taking, but falls short in spending. But besides these, there are other dispositions in the matter of money: there is moderation which is called magnificence, which deals in large sums of money. An excess of magnificence is called vulgarity, and a deficiency is called meanness.” (Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics Book II)]

|

|

|

|

|

Aristotle is at pains to stress that the mean is not an arithmetical mean — that is, it is not possible to arrive at a determination of what is the right action at any given time by means of a quasi-mathematical calculation. He does not regard ethics and politics as precise branches of knowledge. He believes that ethics involves a peculiar form of judgment, and the faculty for making ethical judgments is called “prudence”. He claims that prudence is not a species of any other kind of knowledge. In applying the Doctrine of the Mean we have to make prudential judgments in some kind of non-mechanical way regarding what action is appropriate. [“Virtue is a habit or trained faculty of choice, the characteristic of which lies in moderation or observance of the mean relatively to the persons concerned, in such a way as a prudent man would judge it.”]

|

|

|

Prudence involves being able to see the right principle to apply in a given situation, and to foresee accurately the consequences of an action. It requires deliberation; you are expected to deliberate over the best way to achieve a moral purpose. So to be prudent a man requires practical experience. Young men lack the experience to be completely successful and moral in their actions.

|

|

III |

|

There are other potential alternative bases to a virtue ethics. One such is the approach adopted by Hume. He takes primarily a descriptive view of ethics, and claims that what people call virtue is in every case what is useful to society as a whole. Thus virtue is measured in terms of utility. Having made this observation, Hume in fact argues that people are happiest when they are in tune with the standards of virtue set by their society. It is rational to lead a virtuous life.

|

|

IV |

|

Another virtue theory is that put forward by the British philosopher, Alasdair MacIntyre (After Virtue,1981), who advocates a return to Greek insights into moral life. He is specifically opposed to the duty ethics of Kant on the one side and the consequentialist ethics of utilitarianism on the other. He wants a return to taking moral and intellectual virtues as the starting point in ethics. He claims that the lack of concern for virtue has led to the development of the character types that are expressions of a secular society. Three such types are (1) The Rich Aesthete — a character who pursues more and more pleasure in a grandiose style, who serves to express the fantasies of the bulk of the population, who regard their lives as mundane in comparison; (2) The Bureaucratic Manager, who manages businesses in the most efficient manner, but without regard to moral considerations, being motivated solely by profit; (3) The Therapist, who charges exorbitant fees to listen to the neuroses of hollow people.

|

|

V |

|

If virtue theory is an attempt to carve an alternative approach to ethics, one that is not based on either the duty concept (exemplified by Kant) or the consequentialist principle (illustrated by utilitarianism) then it is questionable whether it represents a genuine alternative.

|

|

|

A theory of virtue tells us what makes certain characters virtuous, and what not.

|

|

|

Aristotle does seek to explain virtue in terms of a guiding principle known as the Doctrine of the Mean, and on analysis this is based on the idea of maximising reason in practical living. Thus, it is ultimately a form of duty ethic, but one that is different from that of Kant. Perhaps the mistake is to regard Kant as offering the only possible form of duty ethic.

|

|

|

By way of contrast, Hume's ethic is not a duty ethic. It is a consequentialist theory, and argues that virtue maximises utility. However, it is not identical to utilitarianism either, so it would be a mistake to identify consequentialism with utilitarianism.

|

|

|

So between Kant's theory and utilitarianism, there is a wide scope for alternative ethical theories. However, virtue theory is not a theory that is distinct from a theory of duty or a theory of consequences, or both.

|

|