|

Descartes: Meditation II |

I. Outline of Meditation II |

|

There are three major arguments in this meditation: (1) the Cogito, which seeks to prove that each person knows that he exists; (2) the inference from the cogito to the idea that man's essential nature is as a thinking being (sum res cogitans); (3) a thought-experiment regarding a piece of wax (the “wax argument”) which aims to show that man is endowed with intellectual powers that enable him to be understand and be acquainted with substance.

|

|

II. The Cogito |

|

Descartes writes

|

|

| It is without doubt that I exist, since I must exist even if I am being deceived. However much [the evil genius] deceives me, so as long as I am conscious of being something, he can never make it so that I do not exist. In conclusion, after deep and careful reflection, it can be asserted that the proposition I am, I exist is necessarily true whenever I express it or conceive it in my mind. |

|

|

|

The term cogito derives from Descartes' other formulation of the argument, to be found in the Discourse on the Method.

|

|

| I decided to reject as false all the reasons that I had previously accepted has having been demonstrated to be truth. I did this firstly because our senses sometimes deceive us, so it is possible that nothing is exactly what we imagine it to be, and secondly because some men deceive themselves by making errors in their reasonings, committing paralogisms even in the simplest cases of geometric proof, and I realized that I was as much prone to make errors as anyone else. Likewise, since any thought or idea that we can have while awake can occur to us in our sleep, I resolved to take everything that ever entered into my mind as containing no more truth than the illusions of my dreams. Nonetheless, immediately after forming this idea I observed that even when I thought that everything was false, it was nonetheless essential that the “I” who is the subject of this thought is something, and so I concluded that I think, therefore I am was absolutely certain and incapable of being overturned as a truth by even the most extravagant skeptical propositions. I concluded that I could without any doubt whatsoever accept this statement as the first principle of Philosophy that I had been looking for. [Descartes: A Discourse on the Method.] |

|

|

|

In Latin the phrase I think, therefore I am is cogito, ergo sum; hence the argument is called the cogito.

|

|

|

It is normal to regard the formulation in the Second Meditation as superior to the formulation in The Discourse on the Method. This is because the argument, I think, therefore, I am creates two potential sources of confusion. Firstly, the introduction of the term “therefore” may make the argument seem like a logical deduction, which it is not, as shall be shown below. Secondly, the phrase “I think” may make it appear that the argument depends on what is called ratiocintation or inner thought, like running words through one's head. In fact, Descartes is referring to consciousness in general and not to a kind of consciousness. He would not regard speech or language as essential to the performance of the cogito. This will become clearer as we proceed to explain what the cogito is.

|

|

|

The cogito has the appearance of being indubitable, but it can be objected that it rests upon a number of assumptions regarding the perception of the self, and is vulnerable to objections posed originally by Hume, and later by Russell.

|

|

|

In the Treatise of Human Nature Hume replies to Descartes as follows

|

|

| For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I can never catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception. When my perceptions are removed for any time, as by sound sleep; so long am I insensible of myself and may truly be said not to exist. And were all my perceptions removed by death, and could I neither think, nor feel, nor see, nor love, nor hate, after the dissolution of my body, I should be entirely annihilated, nor do I conceive what is farther requisite to make me a perfect nonentity. [Hume: A Treatise of Human Nature: Book I, Part IV, Section VI, Of personal identity] |

|

|

|

We need to understand the difference between these two passages, which is the key to the critique of the cogito.

|

|

|

Firstly, we have some kind of experience of ourselves and our personal identity. The question that both Descartes and Hume are addressing here, is, what exactly is this experience?

|

|

|

We shall call this experience the primitive act of self-reflective and self-reflexive consciousness. That is a more long-winded expression for the cogito.

|

|

|

Let us explain this.

|

|

| 1 | | This is an act of consciousness. The mind seeks to bring before itself some experience of its own identity. We seek to become more aware of what we are by meditating on our experience of ourselves. |

| 2 | | This is a “primitive” act. By this, we mean that it is like seeing. It is something that just happens. It is not the result of a deductive inference or the product of another argument. It is a direct awareness of something. In his reply to an objection to his philosophy posed by the Reverend Father Mersenne, Descartes sought to explain this point. “But when we become aware that we are thinking beings, this is a primitive act of knowledge derived from no syllogistic reasoning. [A syllogism is a three line deductive argument. Here the sense is not altered if you substitute “deductive” for “syllogistic” and “deduction” for “syllogism”.] He who says, 'I think, hence I am or exist,' does not deduce existence from thought by a syllogism, but, by a simple act of mental vision, recognises it as if it were a thing that is known per se..” |

| 3 | | It is self-reflective. In this act we are meditating on the nature of the self. We are seeking to find out what the self is. |

| 4 | | It is self-reflexive. Note the change of spelling. A reflexive relation is one that is doubles back on itself. The standard example is the relationship of identity. All objects are identical with themselves. This is a reflexive relation. In the cogito we are seeking to turn consciousness back on itself. The cogito attempts to be self-reflexive. However, it may not actually succeed, and this is a debating point! |

|

|

|

In these two contrasting passages Descartes and Hume present alternative interpretations of what this primitive act of self-reflective consciousness might be.

|

|

|

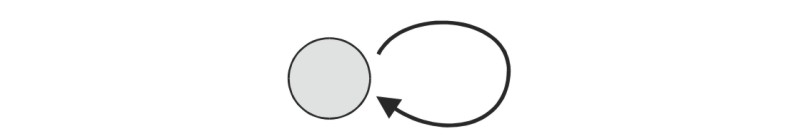

Descartes' interpretation can be represented in the following diagram.

|

|

|

DESCARTES' INTERPRETATION OF THE COGITO

|

|

| The soul looks in on itself and perceives itself, thus verifying its own existence. |

|

|

|

Descartes claims that the mind (or “soul”) can become an object of its own consciousness. In a way that is like seeing a physical object, such as a table or chair, so Descartes claims that we can see our own soul. He will go on to maintain that the soul is a kind of substance, but not a material substance. Material substance is extended in space, but the soul is not.

|

|

|

If this is a kind of “seeing”, then the analogy with physical sight must not be taken too literally, since the soul is not a physical object it will not be possible to see it in the same way. Descartes is claiming that the mind has another power of rational insight or intuition capable of presenting the soul to itself. This is highly debatable, and naturally rejected by empiricists, who have a different interpretation of what this primitive act of self-reflective consciousness produces, as illustrated by Hume's passage.

|

|

|

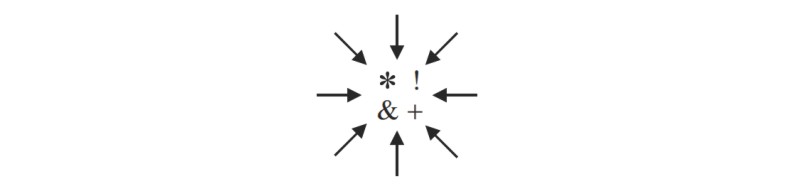

Hume's interpretation can also be represented diagrammatically.

|

|

|

HUME'S INTERPRETATION OF THE COGITO

|

|

|

|

| In this diagram the symbols represent individual ideas, thoughts and sensations, which are the experiences of which we are immediately aware. According to Hume we are aware only of unconnected thoughts, and not of ourselves as an entity. He would claim that it would be more accurate to say, “There is an idea, an experience or a thought here.” |

|

|

|

This critical observation is also supported by Russell in this explanation of the “error” that Descartes has made.

|

|

| But some care is needed in using Descartes' argument. “I think, therefore I am' says rather more than is strictly certain. It might seem as though we were quite sure of being the same person today as we were yesterday, and this is no doubt true in some sense. But the real Self is as hard to arrive at as the real table, and does not seem to have that absolute, convincing certainty that belongs to particular experiences. When I look at my table and see a certain brown colour, what is quite certain at once is not 'I am seeing a brown colour', but rather, 'a brown colour is being seen'. This of course involves something (or somebody) which (or who) sees the brown colour; but it does not of itself involve that more or less permanent person whom we call 'I'. So far as immediate certainty goes, it might be that the something which sees the brown colour is quite momentary, and not the same as the something which has some different experience the next moment. [Bertrand Russell, The Problems of Philosophy.] |

|

|

|

Both Hume and Russell explicitly deny the claim by Descartes that we become directly acquainted with the object to which the term 'I' refers. There are only isolated experiences, no self as such.

|

|

|

However, whilst the philosophical mood of our times favours empiricism, and Hume and Russell might appear to being more careful about what is actually given to consciousness in the cogito the debate is by no means over there. For both Hume and Russell in their attack on Descartes make equally bold statements about what the mind, or human identity is.

|

|

|

Hume writes

|

|

He [Descartes, and other metaphysicians like him] may, perhaps, perceive something simple and continu'd, which he calls himself; tho' I am certain there is no such principle in me.

But setting aside some metaphysicians of this kind, I may venture to affirm of the rest of mankind, that they are nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement. Our eyes cannot turn in their sockets without varying our perceptions. Our thought is still more variable than our sight; and all our other senses and faculties contribute to this change; nor is there any single power of the soul, which remains unalterably the same, perhaps for one moment. The mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance; pass, re-pass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations. There is properly no simplicity in it at one time, nor identity in different; whatever natural propension we may have to imagine the simplicity and identity. The comparison of the theatre must not mislead us. They are the successive perceptions only, that constitute the mind; nor have we the most distant notion of the place, where these scenes are represented, or of the materials, of which it is compos'd. [Hume: A Treatise of Human Nature: Book I, Part IV, Section VI, Of personal identity.] |

|

|

|

In this passage Hume denies that there is a single entity that is the soul. In short, human identity does not exist in the way in which one might intuitively (or naievely) think it does. The human mind is nothing but a “collection of different perceptions”; there is no “simple and continued” object to which the term “I” refers.

|

|

|

Thus, it may be objected that this also goes too far. Whereas Descartes' version of the cogito seems to assert too much, Hume's seems also to deny too much. So it will not come as a surprise to learn that there is a third version of the cogito that is advanced by Kant.

|

|

|

Kant writes

|

|

| The abiding and unchanging 'I' (that is, pure apperception) is the correlative of all our representations, for without it, it would be impossible that we should be conscious of any of them. In truth, all consciousness ... partakes of an all-embracing pure apperception. [Kant: Critique of Pure Reason — Transcendental Deduction A — The A Priori Grounds of the Possibility of Experience. 3. The Synthesis of Recognition in a Concept.] |

|

|

|

In this passage Kant denies that consciousness can ever become an object of its own act of awareness, in the manner in which a thought or a perception can be an object. So he is opposed to Descartes. On the other hand, he also denies Hume's claim that the soul is made only of a “collection of different perceptions”. He claims that consciousness is necessary to every act of awareness. That in order to experience an object one must be aware of it, and this awareness is not contained in the experience, nor is it a pure nothing either. We have a different experience of ourselves to the experience we have of any individual perceptions. The self, or consciousness, is only ever the subject of experience, and never the object of it. Nonetheless, the subject is always present in every experience whatsoever.

|

|

|

Furthermore, the subject is experienced as a single, unitary and abiding self. It is not experienced as a collection of unconnected selves, or separate objects. Although we do not know that the self exists as an object, we experience ourselves as subjects that are single, entire and abiding.

|

|

|

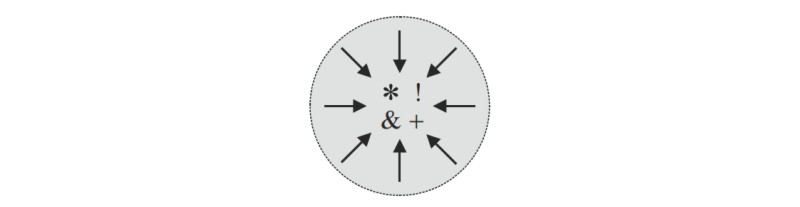

We can also represent Kant's interpretation of the cogito diagrammatically.

|

|

|

KANT'S INTERPRETATION OF THE COGITO

|

|

|

|

Here the shaded circle represents the subjective consciousness that is always present at all times, and which Hume omits.

All objects are objects of consciousness. Subjective consciousness is never an object of its own perception, but is the correlative of all experience whatsoever.

It is assumed that the self is a single, pure abiding awareness transcendent to all experience. |

|

|

|

Whilst Kant's interpretation of the cogito is mid-way between the rationalism of Descartes and the empiricism of Hume, it is not an interpretation that could be made easily compatible with empiricism. It asserts that there is a self, and, whilst denying that the self is a substance (or known to be a substance) it maintains that the self is transcendent to experience. This is not a materialist conception of the self.

|

|

|

Each person must decide how they interpret their own attempt to reflect on their own identity. Hume is definite, and writes “He [Descartes, and other metaphysicians like him] may, perhaps, perceive something simple and continu'd, which he calls himself; tho' I am certain there is no such principle in me.”

|

|

|

*

|

|

|

Another way of expressing this objection to Descartes is through an examination of the meaning of the phrases, “I think” and “I am”.

|

|

|

These are simple, atomic sentences of the English language (capable of translation into French or Latin, the languages in which Descartes wrote). The subject of “I think” is the word “I”, and the predicate is the word “think”. The sentence appears to assert consciousness of an object referred to by “I”.

|

|

|

It could be argued that the cogito arises from a “bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language”. [From Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations.] The sentence “I think” is grammatically similar to “The table is brown”, which we understand in terms of an object (the table) and its property (being brown). However, there are other sentences of our language that cannot be understood in this way. For instance, “It is raining”. Here the term “it” is a dummy subject. There is no object to which “it” refers. It is included in the sentence because we have a psychological need to use sentences that have subjects.

|

|

|

So it can be claimed that the term “I” in “I think” is also a dummy subject; that actually, “I” does not refer to anything, or if it does, it does not refer to a single, pure and abiding object, such as the soul.

|

|

|

The same sort of critique can also be levelled against the use of the term “exists” in “I exist”. We may ask, “What does it mean to exist?” In fact, in could be argued that Descartes is using terms that lack meaning.

|

|

|

However, Descartes could have a reply to this point. The cogito rests on a primitive act of consciousness, and, in order to avoid the charge of depending on the meanings of language, this primitive act must be capable of being performed independently of all language whatsoever. If there is no primitive act of self-reflective consciousness, then the cogito must be meaningless. It is the act of consciousness that gives it content.

|

|

|

Thus, Descartes is asserting in this cogito that there is such a primitive act of consciousness, and further he is claiming vaguely that this act reveals to him that he exists in some sense. At the time of performing the cogito the content of this act is still undefined, but he reserves the right to return to it again and again, and with superior powers of concentration discover more and more about it. The content of the cogito is meant to be refined and developed by all the subsequent arguments in his work. For after all these are presented as a series of meditations, and each meditation seeks to build upon the conclusions of those preceding it.

|

|

|

*

|

|

|

It is also possible to attack the cogito on the grounds that it does not refute the scepticism that Descartes presented in his method of doubt, and particularly fails to refute the “evil genius” argument.

|

|

|

In the evil genius argument Descartes imagines that a powerful and malicious demon is using all his power to convince him of lies. He claims that such a demon could not persuade him that he does not exist, when in fact he does.

|

|

|

The formulation of the evil-genius argument is very subtle. Descartes does not say that the evil genius is all-powerful (or omnipotent).

|

|

| Let me imagine, therefore, not that there does not exist a true God, who would act as the sovereign source of truth, but rather an evil demon, who is cunning, deceptive and powerful, and who employs every means he can to lie to me.

|

|

|

|

However, we may ask, why does he limit the power of the devil in this way? If we are to apply the method of doubt and raise any possibility whatsoever as a means to doubt, why should we not consider the possibility that the devil is all powerful?

|

|

|

If God is all powerful then he could, if he wishes, make me believe anything. It would be a contradiction of his omnipotence to assert otherwise. Therefore, an all-powerful, malicious demon could make me think I existed, when in fact I do not.

|

|

|

We can even go one stage further than this. Hume claims that we exist only as a collection of perceptions. Surely an all-powerful malicious demon could make me think that, although I am only a collection of perceptions, that I am something more than this, and so deceive me into thinking that I am a soul, and exist for all time, when in fact I do not?

|

|

|

So the cogito assumes that the devil could not be all-powerful; but it can be argued that this is not a correct application of the sceptical method proposed by Descartes in his method of doubt.

|

|

|

This assumption is not contained in the cogito and hence the cogito cannot be a self-evident foundation for knowledge. Something else, at least, must be assumed.

|

|

|

In fact, that is not all that must be assumed as this extract from Descartes's Principles of Philosophy will demonstrate.

|

|

Principle VI

That we possess a Free-Will which causes us to abstain from giving assent to dubious things, and thus prevents our falling into error.

But meanwhile whoever turns out to have created us, and even should he prove to be all-powerful and deceitful, we still experience a freedom through which we may abstain from accepting as true and indisputable those things of which we have not certain knowledge, and thus obviate our ever being deceived.

Principle VII

That we cannot doubt our existence without existing while we doubt; and this is the first knowledge that we obtain when we philosophise in an orderly way. |

|

|

|

We note here that in Principle VI Descartes introduces the notion of freewill; but it is in Principle VII that he introduces the cogito. It is clear that by the time of writing the Principles Descartes realised that something further was required in order to make the cogito 'work'. If we are not possessed of the free-will to assent or dissent from propositions, then a powerful, malicious demon could force us to accept as true what was not true.

|

|

|

In summary, following through the logic of this argument we can state that the cogito requires three elements in order to make it 'work'

|

|

| 1 | | The direct apprehension in the cogito of our own existence |

| 2 | | The direct apprehension that whilst there may be a devil he could not be omnipotent. |

| 3 | | The direct apprehension of free-will that gives us the power to agree or not to agree to propositions placed before us, and hence avoid believing lies. |

|

|

|

It would be possible, nonetheless, to rebuild a form of Cartesian rationalism on this basis. In other words, it could be argued that the primitive act of self-reflective consciousness does present us with a direct apprehension of all these truths

|

|

| 1 | | That we exist

|

| 2 | | That the universe is fundamentally benevolent |

| 3 | | That we have free will |

|

|

| It could be argued that the “gift” of freewill (which implies the existence of God) is the prime manifestation of the benevolence of the universe.

|

|

III. The Cogitans |

|

The cogitans is Descartes' attempt to give the cogito further content. He writes

|

|

| But what am I? ... Can I be sure that I posses any of those attributes that ... belong to the body? I pause to reflect, and I consider these attributes in my mind, and I conclude that none of them truly belongs to me. It would be tedious to pause to list them all. Let us move on to a consideration of the attributes of the soul, and see if any of these belongs to me. What about nutrition or walking...? But if it is true that I can have no body, then it is also true that I can neither walk nor eat. Another attribute is that of sensation. But one cannot have feelings without a body, and, furthermore, I have thought I perceived many things during sleep that on waking I realized that I had not experienced at all. What about thinking? And it is here that I find that thought is an attribute that belongs to me; it alone cannot be separated from me. I am, I exist, that is certain. But when is it certain? Just when I think; for it is possible that should I stop thinking completely, then I would likewise completely cease to exist. I am not going to believe in anything unless it is necessarily true: but to be precise, I am nothing more than a thing that thinks, that is, a mind or a soul or an understanding, or a reason, and these are terms that were formerly unknown to me. I am, nonetheless, a real thing and I really exist. But what thing? I have an answer: a thing that thinks. |

|

|

|

The Latin for “I am a thinking thing” is “Sum res cogitans”; hence the argument is known as the cogitans.

|

|

|

An essential property is a necessary property. It is a property without which an object would not be the object it is. To say that consciousness is my essence is to say that I would not be myself if I were not conscious.

|

|

|

Descartes claims that we know ourselves as minds more indubitably than we know ourselves as bodies. He then argues that because of this our essential identity is that of a disembodied mind, so he paves the way for the possibility we could exist without a body.

|

|

|

It could be argued that although we are more intimately aware of ourselves as subjective consciousness, we are nonetheless in fact conjoined to a material body, and when that material body ceases to exist, so does consciousness. This is the point that Hobbes makes in his set of objections to Descartes' philosophy

|

|

| All Philosophers distinguish a subject from its faculties and activities, i.e., from its properties and essences; for the entity itself is one thing, its essence another. Hence it is possible for a thing that thinks to be the subject of the mind, reason, or understanding, and hence to be something corporeal; and the opposite of this has been assumed, not proved. [Thomas Hobbes: Objections III.] |

|

|

|

In other words, although we are only aware of ourselves as conscious entities, this consciousness could not exist without a material body to produce it.

|

|

|

Descartes has a reply to this objection, which is that at this stage of the presentation of his philosophy he has not as yet asserted that body and soul are distinct entities, capable of existing separately. He states explicitly that he only does this in Meditation VI after he has proven the existence of God, and it is only with the knowledge that God exists that he can state categorically that bodies and souls are separate substances and can exist apart from each other. Here is his reply

|

|

| A thing that thinks, he [Hobbes] says, may be something corporeal; and the opposite of this has been assumed; not proved. But really I did not assume the opposite, neither did I use it as a basis for my argument; I left it wholly undetermined until Meditation VI, in which its proof is given. |

|

|

|

If this is the case it may be premature to discuss Descartes' conception of what body and soul are; however, it is normal to do so in this context.

|

|

IV. Dualism |

|

Descartes is a dualist. This means that he believes that minds and bodies belong to separate realms of existence. The mind is composed of spiritual substance; the body is composed of material substance. The essential property of material substance is extension; in other words, material objects occupy a volume of space; the essential property of minds is consciousness (to be a ”thinking thing”).

|

|

|

The concept of substance implies the existence of something that persists over time. Later in this Meditation Descartes will use the example of a piece of wax to illustrate what he means by substance. A piece of wax can melt and yet remain the same wax as before. The notion of substance is used to act as the entity that remains the same despite what other changes occur to its properties.

|

|

|

Later in this Meditation, following his presentation of his “wax argument”, Descartes explains what he means by material subtance

|

|

| It is certain that [the wax] is nothing other that something that is extended, capable of changing shape and capable of being moved. |

|

|

|

By saying that the soul is a substance Descartes is also saying that it is an entity that retains its identity over time, and acts as the eternal and unchanging object that remains the same despite changes in the contents of the mind. A man may undergo some changes in his character as he develops over time, but his identity, the person he is, remains the same regardless of these changes. In order to explain this, Descartes says that the soul (the person that he is) is a spiritual substance.

|

|

|

It is a spiritual as opposed to material substance because the soul is not extended in space. It is a substance because it possesses unity, identity and is abiding.

|

|

|

Descartes conceives of the relationship between mind (soul) and body on the model of a pilot and a ship. The soul (the pilot) directs the body what to do, and the body responds. Likewise the body conveys information to the soul through the medium of the senses.

|

|

|

Modern philosophy has seen a systematic and sustained attack on Cartesian dualism, lead by such philosophers as Wittgenstein and Gilbert Ryle. Since the attack is so thorough a description of it is left to another unit. In this attack it is argued that mind/body dualism is absurd. This is maintained on the grounds of the difficulty of conceiving the mind/body interaction (the psycho-physical gap) and on the accusation that Descartes is making certain errors of logic, such as “category errors”.

|

|

|

There is another criticism of Descartes' identification of identity with consciousness. By a “thinking thing” Descartes does mean a conscious thing. The identification of human identity with consciousness raises problems. “I am, I exist, that is certain. But how often? Just when I think...” This raises the problem of what happens when we are sleeping, for in that case do I not cease to exist since I cease to be conscious?

|

|

|

However, a reply to this could be that consciousness never wholly ceases during sleep, and that sleeping is a form of consciousness, but different from that of waking consciousness.

|

|

|

Nonetheless, the materialist conception of human identity does produce an easy solution to the problem of sleeping. It simply asserts that the body continues to exist whilst the mind is unconscious, and that human identity, in so far as there is any human identity, is closely connected to the identity of the human body.

|

|

V. The “Wax argument” |

|

Descartes writes

|

|

| Consider, for example, this piece of wax. .... Let it be placed near the fire — then its characteristic taste is lost, its odour evaporates, its colour changes, it loses its shape, it is difficult to handle, and if it is hit, it will emit no sound. Is this the same wax as before the change? It has to be admitted that it is; no one ever doubts it, or concludes differently. Then it is certain that the wax could not be any of the things that I have observed through my senses, since everything that I experienced through the sense is changed — the taste, smell, sight, touch and sound are all altered, and yet it is still the same wax. ... I conclude that ... it is the mind alone that perceives [the wax]. |

|

|

|

The wax argument is motivated by an attempt to reiterate the argument of the Mediation in the face of an objection — but surely I do know objects by means of the senses more distinctly than I know objects by means of intellectual insight alone? The wax example intends to demonstrate that the knowledge of material objects depends upon some purely non-sensuous intellectual apprehension of their substance, so that sense-experience cannot form a basis of knowledge. In effect, this argument acts as a refutation of empiricism.

|

|

|

It is claimed that the various transformations that the wax undergoes (in its solid, liquid and gaseous states) do not affect the identity of the wax. Yet there is no sense-impression corresponding to the identity of the wax, which must, therefore, be supplied by the mind alone. Consequently, the mind is endowed with a purely intellectual apperception of it.

|

|

|

Descartes seeks to persuade us that we are capable, by means of our intellect alone, of being acquainted with material substance. His argument is that the wax can take many different forms but yet we know that it remains the same wax regardless of what form it takes. He claims that this shows that our knowledge of the wax must be independent of any particular observation.

|

|

|

However, this argument is not convincing. It is open to the objection posed by Hume that no observation of an object will suggest to us any unobserved properties it may have, unless these have already been shown from experience. A man who has never seen snow cannot imagine what snow would be like. Our knowledge of objects and their causal relations is based on experience. The concept of substance is effectively a hypothesis about observed physical properties, and not something that we intuit directly with the mind (the intellect).

|

|

|

Hume, who would accept the evidence that Descartes cites regarding the changes of the wax, would argue that the correct conclusion to be drawn is that the wax does not have an identity, and that the identity we ascribe to it is an illusion. From the fact that there is no impression corresponding to substance, Hume infers that the notion of substance is strictly meaningless. The validity of Descartes' argument turns upon acceptance of the notion that we do have a grasp of the identity of objects.

|

|

|

Descartes here does distinguish between non-reflective and reflective (judgemental) knowledge. He argues that the knowledge of the substance of the wax derives from a judgement made by the mind. Here the distinction can be used against him. Since the existence of the wax's substance is only a judgement of the mind, there is no need to suggest that the substance is the object of a perception as such.

|

|

|

Descartes presents the wax argument as an aside to his main reconstruction of knowledge from the cogito onwards. Hence, we can ask the question, “How vital is the wax argument to his philosophy?” The wax argument supports the view that the mind has a direct relationship with reality in the form of an acquaintance with substances that may subsequently be shown to be created by God. The relationship between the mind and substance is essential to the validity of the cogito and the cogitans, where Descartes maintains that we have a direct relationship to the substance of our soul. If in the case of the wax argument, the relationship of the mind to material substance is shown not to exist, then this will undermine the creditability of the claim that we know spiritual substance in the same way.

|

|

VII. Universals — the men in the street |

|

Nonetheless, Descartes's wax argument is related to another argument — the problem of universals. In the problem of universals Plato does not specifically seek to demonstrate that we have knowledge of substance, yet he does seek to show us that we have intellectual knowledge that cannot be derived from experience. This knowledge consists of the ability to the mind to perceive similarities and dissimilarities between objects. This means that the mind is perceiving objects by applying concepts. Knowledge of universals is knowledge of the structure of the experience; this is why they are called forms or universals. This argument does not demonstrate that we have knowledge of substance, but does provide a good reason for supposing that the mind has faculties that are independent of material reality.

|

|

|

In an extension to the wax argument Descartes writes

|

|

| An analogous case [to the wax argument] concerns the people passing by on the street below that I can observe through a window. In this case I also do not hesitate to say that I see the men themselves, just as I say that I see the wax; and yet what do I really see through the window except their hats and cloaks, and these might be just coverings for artificial machines that are moved by means of springs? Nonetheless, I deem that there are human beings from the appearance of such, and so I realize that it is by the faculty of judgement alone, which is a mental power, that I draw this conclusion which I thought had been given to me by my eyes. |

|

|

|

This effectively also relates the problem raised by the wax argument to the problem of universals. The concept of a man is a universal. What Descartes' argument here does is remind us that the perceptions that we see of men in the street are strictly speaking not of men as such, but of individual sense-experiences of their hats and cloaks. When in perception we judge that they are men that are walking below on the street, we are applying our conceptual understanding to what we see. Thus, what we see is a function not only of what is impressed on our minds from without but also what we supply of ourselves in terms of our concepts.

|

|

|

The argument over universals was taken up by Hobbes in his Objections to Descartes.

|

|

The ancient peripatetics also have taught clearly enough that substance is not perceived by the senses, but is known as a result of reasoning.

But what shall we now say, if reasoning chance to be nothing more than the uniting and stringing together of names or designations by the word is? It will be a consequence of this that reason gives us no conclusion about the nature of things, but only about the terms that designate them, whether, indeed, or not there is a convention (arbitrarily made about their meanings) according to which we join these names together. If this be so, as is possible, reasoning will depend on names, names on the imagination, and imagination, perchance, as I think, on the motion of the corporeal organs. Thus mind will be nothing but the motions in certain parts of an organic body. [Hobbes:Objections III.] |

|

|

|

Hobbes denies in this passage that there are universals and asserts that the use of terms to denote objects is a matter of convention. Hobbes is a nominalist.

|

|

|

In his reply Descartes defends the notion that the mind has the power to grasp meanings, and that these meanings designate real properties of objects known only to the mind through its intellect.

|

|

| Moreover, in reasoning we unite not names but the things signified by the names; and I marvel that the opposite can occur to anyone. For who doubts whether a Frenchman and a German are able to reason in exactly the same way about the same things, though they yet conceive the words in an entirely diverse way? And has not my opponent condemned himself in talking of conventions arbitrarily made about the meanings of words? For, if he admits that words signify anything, why will he not allow our reasonings to refer to this something that is signified, rather than to words alone? But really, it will be as correct to infer that earth is heaven or anything else that is desired, as to conclude that the mind is motion... [Descartes: Reply to Objections III.] |

|

|

|

This leads into the problem of universals which is a topic for another chapter.

|

|

VIII. Imagination |

|

We will also deal with a minor point concerning Descartes' interpretation of what imagination is. He writes in the context of the “wax argument”

|

|

|

The concept I have of the wax is not the product of the faculty of imagination.

|

|

|

Descartes has adopted the Renaissance theory of imagination here. In the Renaissance is was customary to regard the imagination as a faculty dependent on sensation. Sensation presents sensory objects which are retained in the memory. Imagination is a weaker power of the mind whereby these ideas can be recombined into other objects. For example, I see a mountain and I see a piece of gold, and in my imagination I can combine the memory of both sensory impressions into a new idea, that of a golden mountain. Hume also adopts this theory of imagination in his statements about what fancy is, fancy being another term for imagination.

|

|

|

Thus, Descartes is simply saying that there is no way in which the concept of the wax could be produced by sensation, not directly, nor indirectly through imagination.

|

|