|

The Ontological Argument for the Existence of God |

I

From Descartes: Meditation V

The Existence of God |

| I can derive from my thought the idea of an object, and it follows that all that I clearly and distinctly grasp as belonging to any such object, does in truth belong to it. Applying this principle, I can derive an argument for the existence of God. It is certain that find the idea of God in my consciousness, that is, the idea of a supremely perfect being, in just the same way that I find there the idea of any figure or number whatsoever. I shall now show that I know as clearly and distinctly that an actual, that is, external, existence belongs to God in the same way as I know that anything that can be demonstrated as a property of a figure or number really does belong to that figure or number. Even if the conclusions of all these Meditations were false, I would be certain of the existence of God — at least as certain as I know of any truth of mathematics. I grant that this may appear at first to be mere sophistry rather than compelling truth. But this is only because I am used in the case of every other matter to make a distinction between existence and essence, and this makes me believe simply that God's existence can likewise be distinguished from his essence, which would entail that God can be conceived as not actually existing. But, on closer consideration, it emerges that in the case of God, his existence cannot be separated from his essence, in the same way that the idea of a mountain cannot be separated from the idea of a valley, or the idea of the sum of three angles in a triangle being the same angle as two right angles cannot be separated from the idea of a triangle. It is as impossible to separate the idea of God, that is, the idea of a supremely perfect being, from the actual existence of God, as to conceive of a mountain without a valley. |

|

|

II |

| 1 | | I have an idea of God |

| 2 | | My idea of God is an idea of a supremely perfect Being |

| 3 | | Whatever is perfect must exist. |

| 4 | | Therefore, God must exist. |

|

|

III |

|

There is the question of what this argument purports to prove. Starting with an idea of God, that is with a mental object (in this case, a concept) that is before my subjective consciousness, the argument claims to force the conclusion that there is the necessary, actual, real and external existence of God, that is, the real existence of an object corresponding to my idea of a supremely perfect being, not merely as a mental object before my mind.

|

|

|

Let us make this clear. For the argument to have any content it must act as a means for transporting me out of my merely subjective consciousness, to show me that an object external to my mind, that is a supremely perfect being, must exist.

|

|

|

The formulation of the argument by St. Anslem also makes this transition from the mental to what is external to the mind clear.

|

|

| Now [O Lord] we believe that thou are a being than which none greater can be thought. Or can it be that there is no such being, since “the fool hath said in his heart, “There is no God'”? [Psalms 14:1; 53:1] But when this same fool hears what I am saying — “A being than which none greater can be thought” — he understands what he hears, and what he understands is in his understanding, even if he does not understand that it exists. ... [So] even the fool must be convinced that a being than which none greater can be thought exists at least in his understanding ... But clearly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is actually in the understanding alone, it can be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. But obviously this is impossible. Without doubt, therefore, there exists, both in the understanding and in reality, something than which a greater cannot be thought. |

|

|

IV |

|

It is nowadays common to dismiss this argument without any serious reflection, so it is worth considering why it would “work” if it does work. The explanation would be as follows: that God himself has planted in our minds the concept of his nature, so that we are able to come to know that he must exist, and, further, so obtain objective knowledge of the nature of our existence in general.

|

|

|

This explanation must not be interpreted as making the argument circular. It explains why the argument works, if it is valid, but its validity must be derived from the argument itself. However, there are attempts to dismiss the ontological argument a priori — that is, to demonstrate that no such argument could be valid. The main attempt along these lines comes from the verificationists. Hume offers an early version of this approach in his Enquiries concerning Human Understanding.

|

|

...Or to express myself in philosophical language, all our ideas or more feeble perceptions are copies of our impressions or more lively ones.

To prove this ... when we analyze our thoughts or ideas, however compounded or sublime, we always find that they resolve themselves into such simple ideas as were copied from a precedent feeling or sentiment. Even those ideas, which, at first view, seem the most wide of this origin, are found, upon a nearer scrutiny, to be derived from it. The idea of God, as meaning an infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being, arises from reflecting on the operations of our own mind, and augmenting, without limit, those qualities of goodness and wisdom. |

|

|

|

Hume assumes the empiricist thesis — that all meanings (ideas) come from sense-experience (impressions), and therefore asserts that whatever idea of God we do have, this, too, must be compounded of elements ultimately derived from experience. Since that is the case, no idea of God could lead us to a knowledge of his necessary existence as a Being wholly independent of us.

|

|

|

However, this approach begs the question. If we know that empiricism is right, then the ontological argument must be a fallacy based on a concept that we do not understand, even if Anslem does claim that the fool who denies the existence of God does understand what God means. However, the ontological argument invites you to consider whether empiricism is right. If the ontological argument is valid, then it cannot be that our idea of God is a compound of impressions derived from sense-experience.

|

|

|

Thus, whilst one might deny that we do have an idea of God, or that the idea of God is the idea of a perfect Being, the core of the argument really lies in the premise that whatever is perfect must exist. It is this premise that we must examine very closely.

|

|

|

There is a refutation of the ontological argument in the work of Kant that is taken as the definitive refutation of it, and which centers its attack on this premise that whatever is perfect must exist. However, before examining that argument, it is worth exploring a little further the power of this third premise.

|

|

|

To do so, consider, for example, two chairs. Both chairs are alike in every respect with one exception — one of the chairs exists and the other does not. Both are made of wood, both have four legs, both have the same type of seat, both have the same colour — only, one exists and the other does not. Now, which of these chairs, we may ask, is the better chair? The answer is clearly, the chair that exists. Therefore, it is true that of two objects, the object that is better than any other is the one that exists. Therefore, existence is a perfection. Therefore, since God encompasses every perfection, God must exist.

|

|

|

There is an objection to the ontological argument based on a counter-example. The author of this argument was a contemporary of St. Anslem called Gaunilo. He argued as follows: suppose we substitute “perfect island” for “God” in the argument, we obtain the following.

|

|

| 1 | | I have an idea of a perfect island. |

| 2 | | My idea of a perfect island is an idea of an island that is perfect |

| 3 | | Whatever is perfect must exist. |

| 4 | | Therefore, a perfect island must exist. |

|

|

|

This counter-example seeks to show that the argument must be a fallacy because it has led to the absurd conclusion that a perfect island must exist. Curiously, however, the counter-example does not expose the exact location in the argument of its deficiency, so we are left not really knowing why the argument is a fallacy.

|

|

|

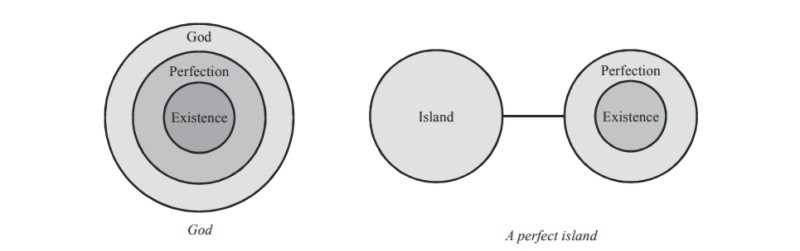

Most commentators now accept that Gaunilo's counter-example is not valid. This is indicated in the counter-example by the way in which it has turned the second premise — My idea of a perfect island is an idea of an island that is perfect — into a redundant tautology — it simply restates what a perfect island is. The second premise of the ontological argument - My idea of God is an idea of a supremely perfect Being- analyses the concept of God to discover that it is the concept of a perfect being. It is no part of the meaning of an island that it should be perfect, but it is part of the meaning of “God” that he is perfect — or so Descartes and Anselm could argue. The form of the ontological argument works only for the concept of God, and for no other concept. The idea of an island only encompasses the idea of a land mass surrounded by water; it is not part of this idea that the land mass should be “perfect”. Only in the case of the concept of God, does the concept imply, as part of its meaning, the idea of perfection. This approach to Gaunilo's objection is implied by Descartes when he comments that the argument may appear sophistical, “... but this is only because I am used in the case of every other matter to make a distinction between existence and essence”. The difference could be represented diagrammatically.

|

|

|

|

|

Descartes's reply to Caterus and Gaunilo

|

|

|

Descartes specifically dealt with this objection in his reply to Caterus's objections to his Meditations.

|

|

| ... we must distinguish between possible and necessary existence, and note that in the concept or idea of everything that is clearly and distinctly conceived, possible existence is contained, but necessary existence never, except in the idea of God alone. For I am sure that all who diligently attend to this diversity between the idea of God and that of all other things, will perceive that, even though other things are indeed conceived only as existing, yet it does not thence follow that they do exist, but only that they may exist, because we do not conceive that there is any necessity for actual existence being conjoined with their other properties; but, because we understand that actual existence is necessarily and at all times linked to God's other attributes, it follows certainly that God exists. |

|

|

V |

|

It is now time to turn to the principle objection to the ontological argument, which is found in Kant's Critique of Pure Reason.

|

|

If in a proposition asserting an identity, [Note: Such as “A perfect island is a perfect island”.] I deny the predicate while retaining the subject, a contradiction follows. [Note: In “England is a perfect island” the subject is “England” and the predicate is “...is a perfect island”. Denying the predicate in a sentence expressing the law of identity is equivalent to stating, for example, both “A perfect island is a perfect island” and “A perfect island is not a perfect island”, which is a contradiction.] Consequently, in such a proposition, the predicate necessarily belongs to the subject. But if we reject subject and predicate together, then no contradiction follows, for there remains nothing to be contradicted. To suppose a triangle exists without three angles is self-contradictory, but there is no contradiction if the triangle is not thought to exist, along with its three angles. The same point applies to the concept of an absolutely necessary being. If we deny the existence of a thing, we deny its existence along with all of its properties, and there is no question of entering into a contradiction. For there is nothing outside the proposition that is contradicted as a result, since the necessity of the existence of the object is not derived from anything external to the proposition, and there is nothing within the proposition that is contradicted, since we have denied both the existence of the thing along with all of its properties. “God is omnipotent” is a necessarily true judgment. We cannot deny the attribute of omnipotence to God once we have posited the existence of God, who is an infinite being. It is true that an infinite being is identical to an omnipotent being. But if we say, “There is no God”, neither God's omnipotence nor any other of his predicates are given; all are rejected at one and the same time together with the subject, and there is therefore not the least contradiction in such a judgment.

... [In reply to the ontological argument] my answer is as follows. There is already a contradiction when one introduces the concept of existence — no matter how this is disguised — into the concept of a thing that we profess to be thinking of solely in terms of its possibility. If we allow that move as legitimate, then an apparent victory has been won; but actually nothing at all has been said, for the assertion is a mere tautology. We must ask: is the proposition that this or that thing exists an analytic or synthetic proposition? (By doing so we acknowledge that the thing can possibly exist.) If the proposition is analytic, then the assertion that the thing exists adds nothing to the idea of the thing.... But if, on the other hand, we acknowledge, as every reasonable person does, that all existential propositions are synthetic, then how can we profess to maintain that the predicate of existence cannot be rejected without leading into a contradiction? Such a feature is found only in analytic propositions, and this is precisely what makes them into analytical sentences.

... “Existence” is obviously not a real predicate, that is, it does not signify a concept of something that can be added to the concept of a thing. It merely signifies that a thing is posited, or it asserts that some qualities exist by themselves. In logic existence merely signifies the copula of judgment. The proposition, “God is omnipotent”, contains two concepts, each of which signifies a referent — God and omnipotence. The little word “is” does not add a new predicate, but only serves to establish the relationship between the predicate [“omnipotence'] and its subject [“God”]. When we say “God is”, or “There is a God”, we attach no new predicate to the concept of God, but only posit the subject itself along with all its predicates; in fact, we posit God as an object to which my concept of him refers. The content of both my concept of God, and God himself [the object of my thought] must be the same, and [by the addition of the word “is”] nothing can have been added to the concept. The judgment [“God is”] expresses still only what is possible although I think of its object [God] by use of the expression “God is” as given absolutely. Another way of putting this is that what is thought of as real has no more properties than what is thought of as merely possible. A hundred real thalers [Note. A thaler is a unit of currency.] does not contain any more coins than a hundred possible thalers. The hundred possible thalers signifies the concept of the hundred thalers, and the hundred real thalers signifies the real object to which these hundred possible thalers corresponds. But suppose that the hundred real thalers has an additional property to the hundred possible thalers, then the hundred possible thalers would not express the whole meaning of the hundred real thalers, and it would not be an adequate concept of it. [The correspondence relationship between the idea of a hundred thalers and the real object to which this idea corresponds establishes that the properties of both the hundred possible thalers (the idea of the thalers) and the real thalers (the object) must be the same, for otherwise the idea would not be an idea of the object.] My financial position is undoubtedly very differently affected by the existence of a hundred real thalers than by the mere thought of them, that is, the thought of a possible hundred thalers! The existence of an object is never analytically contained with the concept of that object; existence is always added to a concept synthetically. However, the hundred imaginary thalers is not in the least bit increased if indeed there are a hundred real thalers which exist outside the concept of the imaginary thalers. |

|

|

|

This is not at first glance an easy passage, and it uses some logical terminology that can be off-putting.

|

|

|

It is also usual to summarise this objection under the dictum, existence is not a predicate. However, this is not quite accurate, the dictum should be existence is not a real predicate, or existence is not a property. We shall seek to explain this distinction.

|

|

|

Let us begin with the subject/predicate, object/property distinctions. In the expression, “The Tower of London is a very large”, the expression “The Tower of London” is the subject, and the remaining expression in the sentence, “... is a very large”, is the predicate. These are grammatical distinctions. It appears that declarative statements in our language all follow a subject/predicate pattern.

|

|

|

It is usual for the subject to be thought of as referring to an object. The words “The Tower of London” refer to a castle. Likewise, the predicate “... is large” refers to a property of that castle.

|

|

|

It seems that the habit of forming subject/predicate sentences is a psychological need, and we form such sentences even when there is no logical need for them. For example, in the sentence, “It is raining” the term “it” has no logical function. It is a grammatical subject, but it has no referent — there is no object in the world to which “it” refers. Thus “it” in, “It is raining” is a grammatical subject, but not a real subject; we could also say that it is not an object.

|

|

|

In the expression, “The Tower of London exists”, the predicate “... exists” is a grammatical predicate (it follows the same grammatical rules as other predicates such as “... is large”) but it is not a logical predicate — there is actually no property to which it refers. Or, in the words of Kant, no property has been added to the Tower of London when we assert of it that it exists.

|

|

|

In other words, because of the grammatical similarity between “The Tower of London is large” and “The Tower of London exists” we have been “bewitched” into thinking that existence is a property in the same way that being large is a property.

|

|

|

There is a clear distinction between the logic of predicates like “... is large” and predicates like “... exists”.

|

|

|

To pursue and clarify this objection further: what do expressions like “The Tower of London exists” mean? How and when are they used in our language? Here is an example of the way in which “existence” is used: Imagine a perfect island! It has perfect beeches, perfect restaurants and perfect hotel, which all charge perfect prices! Furthermore, it exists, and if you sign up today you can travel there on your next holiday!

|

|

|

In this example the expression “it exists” signifies that an object originally thought of as existing in thought only (as an imaginary, or merely possible object) must now be thought of as existing in reality (as an external, or actual object). The term “... exists” changes the manner in which you think of an object, but it does not add a property to the object. The properties of the imaginary and real island are the same both before and after the introduction of the phrase, it exists.

|

|

|

So every object that is thought of exists, but some objects exist merely as thoughts or concepts, and others exist as actual objects, external to thought. As Kant puts it, real money is very different from imaginary money. But imaginary money can be used to pay bills — in stories and works of fiction!

|

|

|

The ontological argument is based on the fallacy of taking a merely grammatical predicate (“... exists”) as standing for a real property of objects; hence the intelligence is bewitched into thinking that it can deduce knowledge about the objective reality that exists independently of our minds by analytical consideration of the content of our ideas alone. Our reason does not have that capacity — or, at least, if it does, the ontological argument does not demonstrate it.

|

|