|

The Teleological Argument for the Existence of God |

I

From William Paley: Natural Theology |

In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there, I might possibly answer, that, for anything I knew to the contrary, it had lain there for ever; nor would it, perhaps, be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place, I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given — that, for anything I knew, the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone? why is it not as admissible in the second case as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, viz., that, when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day; that, if the different parts had been differently shaped from what they are, if a different size from what they are, or placed after any other manner, or in any other order than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all would have been carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use that is now served by it.

... This mechanism being observed, (it requires indeed an examination of the instrument, and perhaps some previous knowledge of the subject, to perceive and understand it; but being once, as we have said, observed and understood,) the inference, we think, is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker; that there must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use.

... Every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater and more, and that in a degree with exceeds all computation. I mean that the contrivances of nature surpass the contrivances of art, in the complexity, subtlety, and curiosity of the mechanism; and still more, if possible, do they go beyond them in number and variety; yet in a multitude of cases, are not less evidently mechanical, nor less evidently contrivances, nor less evidently accommodated to their end, or suited to their office, than are the most perfect productions of human ingenuity... |

|

|

II |

| 1 | | Nature is highly ordered, being governed by laws. |

| 2 | | Let us call this the “design of nature”. |

| 3 | | The mechanism of a watch is put there by a watch-maker. |

| 4 | | Therefore, the design of nature must have been made by a designer. |

| 5 | | God is this designer. |

| 6 | | Therefore, God must exist. |

|

|

|

This argument is also called the Argument from Design.

|

|

III |

|

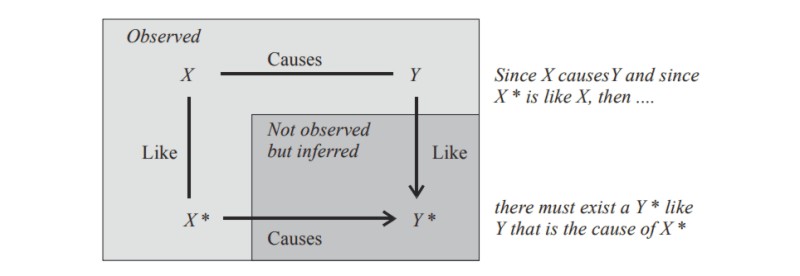

The argument is based on an analogy between one relationship of cause and effect to another. The general schema for an argument by analogy in this case is as follows.

|

|

|

|

|

Argument by analogy in the teleological argument

|

|

|

We argue by analogy from observed relations to an unobserved entity.

|

|

|

No argument by analogy is deductively sound — that is, it is not true that if the premises of the argument are true then the conclusion could not possibly be false. Therefore, it is possible to object to the teleological argument from this point of view. It is not necessary that the conclusion must follow. As an argument to prove the existence of God generally presents itself as a conclusive reason for believing in God's existence, this could be taken as the only objection to the teleological argument that is required.

|

|

|

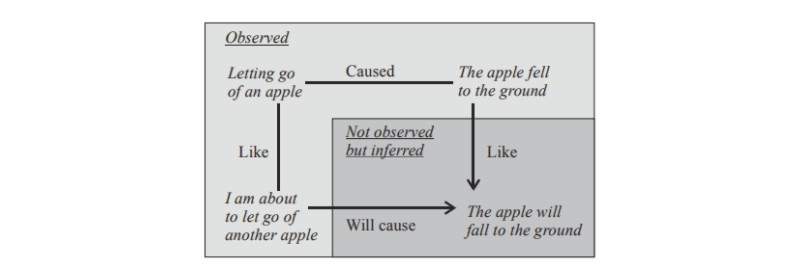

However, arguments by analogy are much more common than the reader may realize — they form the very backbone of scientific reasoning. Strictly speaking, no two events are identical, and it is only because we implicitly accept an argument by analogy that we are able to apply any past observations to present circumstances. For example, when I propose to drop an apple the event is strictly wholly distinct from any other event involving a falling apple. I argue by analogy between the event of letting go of the apple and other events where objects were allowed to fall, to the conclusion that I expect the apple to fall.

|

|

|

|

|

Argument by analogy in inductive reasoning

|

|

|

Since this kind of argument is intrinsic to our interpretation of our experience, this means that it is difficult to reject the argument from design out of hand. This is the same problem that Hume faced when he encountered the argument, and why he felt it necessary to refute it in detail. His refutation in the Enquiries, developed more fully in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion are taken by most philosophers as definitive examples of the refutation of any argument.

|

|

|

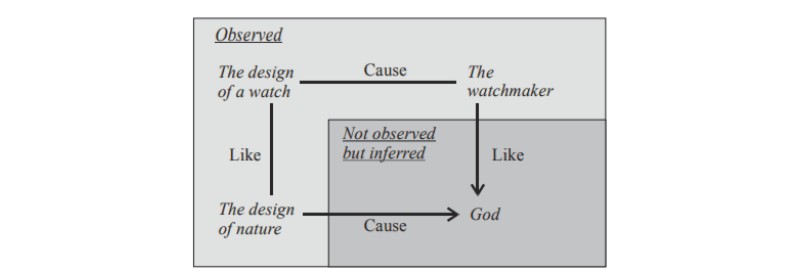

Applied to the existence of God, the analogy in the argument from design can be represented as follows.

|

|

|

|

|

Argument by analogy in the teleological argument

|

|

|

Hume's objection to the argument is based on the weakness of the analogy. An analogical argument is based on the close similarity between the different terms. The less similarity there is between these terms, the weaker the analogy. In what sense can we say that the design of nature, by which we mean the regularity that we observe in the laws of nature, is like the design of a watch? And if we say they are alike, in what sense is a watchmaker like God? These questions clearly provoke the answer: not very much or even not at all. It is this response that Hume probes in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion.

|

|

|

From David Hume: Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion

|

|

Cleanthes is defending the argument from design, and Philo, who is speaking in this extract, is subjecting it to critical scrutiny. A third member of the party is Demea, who represents the old dogmatic view of theology, and defends the medieval proofs of the existence of God such as the cosmological argument. Demea does not speak in this extract..

That a stone will fall, that fire will burn, that the earth has solidity, we have observed a thousand and a thousand times; and when any new instance of this nature is presented, we draw without hesitation the accustomed inference. The exact similarity of the cases gives us a perfect assurance of a similar event, and a stronger evidence is never desired nor sought after. But wherever you depart, in the least, from the similarity of the cases, you diminish proportionately the evidence, and may at last bring it to a very weak analogy, which is confessedly liable to error and uncertainty. After having experienced the circulation of the blood in human creatures, we make no doubt that it takes place in Titius and Maevius; but from its circulation in frogs and fishes it is only a presumption, though a strong one, from analogy that it takes place in men and other animals. The analogical reasoning is much weaker when we infer the circulation of the sap in vegetables from our experience that the blood circulates in animals; and those who hastily followed that imperfect analogy are found, by more accurate experiments, to have been mistaken.

If we see a house, Cleanthes, we conclude, with the greatest certainty, that it had an architect or builder because this is precisely that species of effect which we have experienced to proceed from that species of cause. But surely you will not affirm that the universe bears such a resemblance to a house that we can with the same certainty infer a similar cause, or that the analogy is here entire or perfect. The dissimilitude is so striking that the utmost you can here pretend to is a guess, a conjecture, a presumption concerning a similar cause; and how that pretension will be received in the world. I leave it to you to consider.

|

|

|

|

Some other relevant points: a watchmaker works with existing materials, governed by the laws of nature; a God produces the world from nothing and creates laws of nature where no laws existed before. We cannot say these are similar!

|

|

|

Suppose I was marooned on an island and discover a watch in on the sandy beech. I infer that there must have been a maker of that watch. But in so doing I proceed on my past experience of watch-makers. A watch-maker is a person, and I have met other people, some of whom may have been watch-makers. But have I met God? Or, have I met other supernatural beings — gods. In the case of the argument from design, I proceed entirely from the known to the unknown, and, as Hume rightly says, this renders the analogy very weak indeed.

|

|

|

There is also no guarantee that the creator of the universe is still alive, or that there were not many creators, who worked in a committee to make this world.

|

|

|

The whole argument makes God into a physical being, rather like the watch-maker — a “person” whom you expect to meet around the corner. This is not what God is to religious people. There is no necessary connection between the God who designed nature, and a supremely benevolent deity. We would not be able to infer from this argument any definite property of the deity (or deities) other than that he (or they) designed nature.

|

|

|

Reflections of this kind, in the words of Hume, “at last bring us to a very weak analogy, which is confessedly liable to error and uncertainty.”

|

|

IV |

|

The problem of evil is the problem that the existence of suffering and pain in this world is not consistent with the concept of a benevolent, omnipotent deity.

|

|

|

If one has a prior faith in the existence of God, there are many possible answers to the problem of evil. Notwithstanding the very real nature of suffering in this world, the suffering of innocent children, and the presence of natural evil, in the form of volcanic eruptions and the like, it is possible for a person with a strong faith in the existence of God to reconcile any amount of evil with the existence of God. In the final resort there is the recourse of mysticism, and the freewill defence has a lot of force.

|

|

|

Nonetheless, this response to the problem of evil is only possible if one proceeds from faith in the existence of God to a defence of how his existence is compatible with the existence of evil in this world. But such an argument cannot be offered when the existence of God is inferred from the evidence of his existence in the design of nature. If one concludes that God exists because of the design of nature, then any imperfections in the design of nature must also be attributed to God. Thus, to ground one's belief in God in the argument from design is to leave one incapable of finding an answer to the problem of evil.

|

|

|

Hume explores this difficulty in the following passage.

|

|

Besides, consider, Demea: This very society by which we surmount those wild beasts, our natural enemies, what new enemies does it not raise to us? What woe and misery does it not occasion? Man is the greatest enemy of man. Oppression, injustice, contempt, contumely, violence, sedition, war, calumny, treachery, fraud — by these they mutually torment each other, and they would soon dissolve that society which they had formed were it not for the dread of still greater ills which must attend their separation....

And is it possible, Cleanthes, said Philo, that after all these reflections, and infinitely more which might be suggested, you can still preserve in your anthropomorphism, and assert the moral attributes of the Deity, His justice, benevolence, mercy, and rectitude, to be of the same nature with these virtues in human creatures? His power, we allow, is infinite; whatever He wills is executed; but neither man nor any other animal is happy; therefore, He does not will their happiness. His wisdom is infinite; He is never mistaken in choosing the means to any end; but the course of nature tends not to human or animal felicity; therefore, it is not established for that purpose. Through the whole compass of human knowledge there are no inferences more certain and infallible than these. In what respect, then, do His benevolence and mercy resemble the benevolence and mercy of men?

Epircurus' old questions are yet unanswered.

Is He willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then is He impotent? Is He able but not willing? Then is He malevolent? Is He both able and willing? Whence then is evil? |

|

|