|

Human Identity |

I

The problem of human identity |

|

The modern school of thought, represented by the American school of realists, and by Wittgenstein and Ryle, endeavour to debunk the Cartesian view of the mind. This leaves the field open for materialist and mechanist explanations of mental processes.

|

|

II

The logic of identity relations and the Heraclitan paradox |

|

Identity is said to be a reflexive, symmetric and transitive relations. These are logical terms which we shall immediately proceed to explain. The problem with the materialist conception of mental processes can be briefly summarized as follows: it leads to a concept of human identity that is not transitive. We will not proceed to expand on this statement and explain it.

|

|

|

When dealing with identity it is correct to distinguish between identity as a property of names (that is, as a property of terms of our language) and identity as a property of objects. In the latter case, identity is hardly a property at all — it is not something like “being red” that can be regarded as an attribute of an object. Identity of objects is said by logicians to be the relation that every object bears to itself. An object is identical to itself.

|

|

|

But identity is an important concept because of its role within language. Proper names refer to objects. Usually, different names denote different objects (have different referents). However, sometimes different names refer to one and the same object, and in this case we may assert that the two names are identical — that is, are names of the same object. This is the whole point of the language of identity. For example, the expressions

|

|

| (a) | | 2 + 2 = 4 |

| (b) | | The evening star is the morning star. |

|

|

|

are sentences asserting the identity of names. What this means, in these examples, is that the expression '2 + 2' names the same object as the expression '4'; the expression 'the evening start' names the same object as the expression 'the morning star'. [Both the evening star and the morning star are aspects of the planet Venus, which can also be discovered to be the brightest object in the sky after the Sun and the Moon.]

|

|

|

The need for the identity relation arises from psychology as much as anything. If we were gods and knew everything, then we would have no special need for sentences of the above kind. We would know everything about every object, so we would know every possible name of every object. However, the expression '2 + 2 = 4' can represent a substantial discovery — every child at some stage learnt it. It is because we don't know everything about objects that we can discover some identity between different names of the object. Each name has a referent, but also, what the logician Frege called, a “sense”. The sense is the manner in which the referent is given. In the case of the evening and morning star — a very bright object, like a star, appears in the morning; another very bright star, also appears in the evening. It is assumed they are different stars. Then someone follows their paths through the sky in relation to other stars, and makes the claim that they are in fact the same star. It is also discovered that they are moving around, and that star is discovered to be a planet, and given the name of Venus.

|

|

|

We need the identity of names because our knowledge of objects is limited.

|

|

|

In logic we say that a relations is an identity relation when it possesses three properties. These are

|

|

| 1 | | It is reflexive. That is, it bears the relation to itself. “A = A”. |

| 2 | | It is symmetric. That is if “A = B” then “B = A”. |

| 3 | | It is transitive. That is, if “A = B” and “B = C” then “A = C”. |

|

|

|

These are not properties of objects, but properties of the names of objects. In the above examples, the letters, A, B and C stand for names of objects. Thus, for example, if

|

|

A = 'the morning star'

B = ' the evening star'

C = 'Venus'

|

|

|

then the third property states, that “if 'the morning star' is a name of the same object as 'the evening star', and 'the evening star' is a name of the same object as 'Venus', then 'the morning star' is the name as the same object as 'Venus'.”

|

|

|

In the context of a materialist/mechanist interpretation of human identity, it is the transitive relation that gives cause for concern.

|

|

|

To understand why we need to examine the transitivity property more closely. By asserting this property, an identity relation cannot represent the following possibilities.

|

|

|

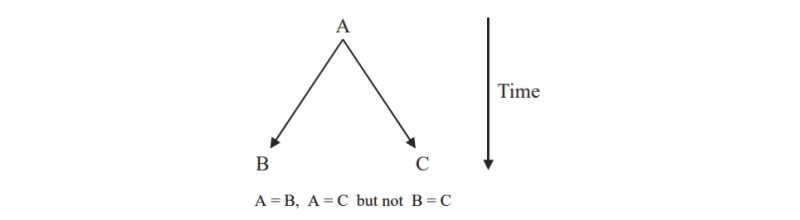

(a) Branching of “identity”

|

|

|

|

|

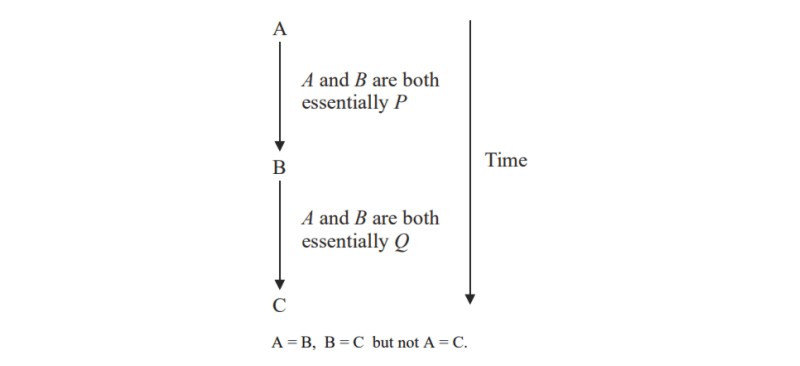

(b) Substantial change (change of essence)

|

|

|

|

| What is being denied here, for example, is that one and the same object could not be over one period of time one kind of thing, say a fish, and then for another period of time another kind of thing, say a stone. A fish cannot turn into a stone. |

|

|

|

Paradoxically, the Cartesian concept of human identity is one that is reflexive, symmetry and transitive. The concept of a soul provides an object that cannot split into two identities, nor can it undergo a change of essence. However, there are problems with the Cartesian concept of the soul. We have already seen the attack on it posed by modern realists and by Wittgenstein and Ryle. There would be practical problems in applying it as well. How would I go about determining whether the man in front of me has the same soul as the man who visited me the day before? Other people's souls cannot be directly seen.

|

|

|

In practice, we base our judgement that this person is the same person as I saw yesterday on the both (a) psychological and (b) physical criteria. Usually, if someone comes into my room and he looks like the same person I met the day before, I shall assume that he is. If this person starts behaving oddly, I may start to question that assumption. Then I will introduce psychological criteria. If it is my business or job to do so, I may ask him if he remembers being the person who visited me before.

|

|

|

This might make it seem that psychological criteria (such as having the same memories) are held in more esteem that physical criteria. However, it is the spirit of our age to reverse this primacy, and there is a tendency to regard the physical continuity of the body as a more important indicator of continuing identity.

|

|

|

Likewise, if the Cartesian concept of the soul is rejected, then materialists would argue that the only object that can form the basis of human identity is the body.

|

|

|

However, here we encounter a problem. The identity of large-scale (macro) physical objects is not transitive. Strictly speaking an identity relation (in the sense of a reflexive, symmetry and transitive relation) cannot be supplied for macro physical objects.

|

|

|

This is expressed in the Heraclitan paradox, briefly, “no river is the same river as it was a moment before”. To give a slightly fuller illustration of the paradox.

|

|

| Suppose the hero Parris bathed in the river Scamander on the first day of summer, and then again on the last day of summer. A river is water. But Parris did not bathe in the same water at the end of summer as he did at the beginning. Therefore, Parris did not bathe in the same river Scamander on both days. |

|

|

|

The problem here is that large-scale physical objects are composites of small scale physical objects. For example, molecules are composites of atoms. Perhaps there are some very tiny objects (the ultimate atoms) that retain their identity and can never undergo any change of essence (though it might be difficult to find them, even protons decay into something else after a sufficiently long period of time). If we change the composition of a large scale object, it has undergone a substantive change. It is literally not the same composition as the one we had before. Most of the time we simply ignore this fact, and act as if the object was the same composite as before. For example, with the river, we talk about bathing in the same river, but if the river is nothing but the composite of its parts, the water that flows through it, strictly speaking it is not the same river!

|

|

|

All large scale material objects are in a state of constant change and flux. A table is gradually being worn away; a bedroom wall receives a new coat of paint. The body is no exception, in fact, the material components of the body are said to be completely changed every seven years. You want to say that you are the same person that you were seven years ago, but clearly you don't have the same body. But if the identity of persons is based on the identity of bodies, then, literally, you are not the same person either.

|

|

|

Here are some other problems that relate to this problem of the material conception of identity and its relation to human identity.

|

|

“Star Trek”

“Beam me up Scotty.” - What philosophical problem must Scotty solve first?

Amoeba

When an amoeba divides, which half is the same amoeba as the amoeba that existed before the division?

The Ship of Theseus

The National Museum of Free Enterprise Land has in its possession the ship of Theseus. This is a very ancient historical treasure. Unfortunately, at one stage the timbers of the ship were slowly decaying. Piece by piece the rotten planks were exchanged for new ones — until in fact the “ship” was entirely composed of new material. Unknown to the governs of the Museum in Free Enterprise Land, agents from the Republic of Common Property had been stealing the rotten discarded pieces one by one. They treated them with a special preservative, which only they possessed. These agents were subsequently able to reconstruct the ship in the People's Museum of the Republic. Given that the process is now complete, which of the two museums possesses the real ship of Theseus?

Brain Transplant

A mad scientist decides to make an interesting experiment. He takes to men from the street, one called Smith and the other Jones, and, operating on them under anaesthetic, he swops over their brains. Which is now what was Smith? |

|

|

|

It seems that if we adopt a physicalist view of human nature, then we will be unable to provide a criterion of human identity that is transitive.

|

|

|

In fact, rather than baulk at this, many modern philosophers are acknowledging this as a logical consequence of materialism. This is illustrated by the work of Thomas Nagel. In his essay on Brain Bisection the concept of a single subsisting self is under attack. Nagel is not upset about this. His attitude is that if the disappearance of the “I” is a consequence of recent scientific experimentation and philosophical enquiry, then so much the better. Derek Parfit also agrees. He believes that the elimination of the “I” from philosophy will have the beneficial effect of reducing the level of ethical egoism. Since we do not have an identity, we also do not have an ego. The appearance of having an ego, which can serve as the end of our actions, is an illusion. Dispense with the illusion, and you dispense with the negative ethical egoism.

|

|

From Thomas Nagel: Brain Bisection and the Unity of Consciousness

... the personal, mentalist idea of human beings may resist the sort of co-ordination with an understanding of humans as physical systems, that would be necessary to yield anything describable as an understanding of the physical basis of mind. ... It is the idea of a single person, a single subject of experience and action, that is in difficulties.

... It may be impossible for us to abandon certain ways of conceiving and representing ourselves, no matter how little support they get from scientific research. This, I suspect, is true of the idea of the unity of a person: an idea whose validity may be called into question with the help of recent discoveries about the functional duality of the cerebral cortex. |

|

|

|

Nagel describes the physiology of the brain. The brain consists of two hemispheres both connected to the spinal column and also connected to each other by a band of nerve fibres called the corpus callosum. The neurologists R.E. Myers and R.W. Sperry found a technique for severing the corpus callosum, first in cats, then monkeys. There is also a treatment for epilepsy involving the severing of the corpus callosum. When this is done it can be shown that the two hemispheres of the brain are capable of functioning independently of one another. People (and animals) with split brains function as if they had two brains, and two identities, not one. He continues

|

|

| What one naturally wants to know about these patients is how many minds they have. ... If we decided that they definitely had two minds, then it would be problematical why we didn't conclude on anatomical grounds that everyone has two minds, but that we don't notice it except in these odd cases because most pairs of minds in a single body run in perfect parallel due to the direct communication between the hemispheres which provide their anatomical bases. |

|

|

|

Nagel concludes that the notion that human beings have a permanent identity is an illusion.

|

|

| The fundamental problem in trying to understand these cases in mentalistic terms is that we take ourselves as paradigms of posychological unity, and are then unable to project ourselves into their mental lives, either once or twice. But in thus using ourselves as the touchstone of whether another organism can be said to house an individual subject of experience or not, we are subtly ignoring the possibility that our own unity may be nothing absolute, but merely another case of integration, more or less effective, in the control system of a complex organism. This system speaks in the first person singular through our mouths, and that makes it understandable that we should think of its unity as in some sense numerically absolute, rather than relative and a function of the integration of its contents. |

|

|

III

Ethical conclusions |

|

Materialists generally associate themselves with utilitarianism. J.C.C. Smart is both a materialist and a utilitarian.

|

|

|

Materialists sometimes claim that the in exposing human identity as a myth they open the way for a new morality —one that does not place any primacy on human identity as sacrosanct. With the ego exposed as a non-existent myth, the way is opened, they claim, for a morality based on universal benevolence, in which no person's pleasures and pains are seen to be more important than another's. This line of argument is illustrated by Derek Parfit.

|

|

From Derek Parfit: Personal Identity

It is sometimes thought to be especially rational to act in our own best interests. But I suggest that the principle of self-interest has no force.

... If this is so, there is no special problem in the fact that what we ought to do can be against our interests. That is only the general problem that it may not be what we want to do.

... Egoism, the fear not of near but of distant death, the regret that so much one's only life should have gone by — these are not, I think, wholly natural or instinctive. They are all strengthened by the beliefs about personal identity which I have been attacking. If we give up these beliefs, they should be weakened. |

|

|