|

Class Structure in Western Societies |

How many classes are there? |

|

It is usual to draw a distinction between the working class and the middle class. From a Marxist perspective both belong to the proletariat as a whole. Usually, the working classes are regarded as undertaking manual jobs, and the middle-classes as undertaking non-manual jobs. The working classes are further sub-divided into unskilled, semi-skilled and skilled manual workers. The middle classes are sub-divided into routine non-manual labour, such as clerical and secretarial work, intermediate non-manual labour, such as teachers and nurses, and professionals, such as doctors, lawyers, accountants and senior managers. Owing to deindustrialisation, there has been a general shift in the proportion of those working in manual jobs to those working in non-manual jobs.

|

|

|

There are also gender differences to consider — women are less likely to have manual jobs than men, but they are more likely to have jobs belonging to the lower grades of the non-manual spectrum — that is, have routine non-manual jobs, or occupy the lower grades of intermediate non-manual labour, such as nursing.

|

|

The Middle Classes |

|

The middle class is usually defined to be those people having non-manual occupations. This distinction appears to correlate with income — that is, people with non-manual jobs tend to earn more than people with manual jobs. According to Westergaard and Resler, the average male non-manual wages was 176% greater than the average male manual wage.

|

|

|

However, this approach to the middle classes may be criticised. Firstly, Marx argues that there are only two classes — the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and that the distinction between manual and non-manual work is either bogus or obscures the true economic position of the proletariat by suggesting that it is more divers than it really is. Secondly, on the contrary, the middle class may be viewed as non-homogenous and highly differentiated, and it may be argued that it is of little use to group together secretaries with higher professionals, since their economic situation and life-styles are very different.

|

|

|

Small employers are usually seen as part of the middle-class. Marx called them the petty bourgeoisie. According to Guy Routh there has been a decline in the number of small employers over the C20th — from 763,000 in 1911 to 621,000 in 1971. However, since 1980 there has been a reversal of this trend, with self-employed and small employers rising as a total from 1,954,000 in December 1971 to 2,902,000 in June 1993 according to government statistics.

|

|

|

Professionals are also viewed as part of the upper middle-class, and Routh estimates that employment in the professions has risen from 4.05% in 1911 to 20.1% in 1985, owing to the increasing clerical demands made by modern business, and to the expansion of the welfare state that has increased demand is some professions (for example, the medical profession) and created other new professions (for example, social worker). There is also a distinction drawn between higher professionals, which include the legal, medical, university academic, scientific and engineering professions, and lower professionals, which include the teaching, nursing and caring professions.

|

|

|

Functionalists interpret professionals as fulfilling important, necessary functions within the organic whole. The functionalist interpretation has been attacked by Ivan Illich in Medical Nemesis, in which he claims that the “medical establishment has become a major threat to health”. He argues that it is hygiene and environment that are the major sources of good health, and that illness in society is correlated to poor hygiene and unhealthy environments, as well as to the materialist culture of acquisitiveness. Health provision is not the cure for social ills of this kind, and in fact obscures the problem. Medical treatment “is but a device to convince those who are sick and tired of society that it is they who are ill, impotent and in need of repair.” In this way, the medical profession, by obscuring the real nature of social evil, contributes to ill health rather than cures it.

|

|

|

According to Barbara and John Ehrenreich there exists a distinctive professional-managerial class consisting of “salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations.” This group comprises 20-25% of the USA population in their opinion and includes engineers, managers, administrators, marketing advisers, entertainers, social workers, psychologists and teachers. So they divide society into three classes, not two — that is, the working class, the professional-managerial class and the bourgeoisie. This professional-managerial class has the following functions: firstly, to organise production; secondly, the control the working-class; thirdly, to maintain the ideology of the ruling classes; fourthly, to promote the design of goods and their consumption, and thus maintain capitalism which is based on mass consumption. Entry to the professional-managerial class is largely by attainment of educational qualifications. Nonetheless, they maintain that membership of this class is relatively closed since the class reproduces itself by investing heavily in education. In other words, in their view, there is little social mobility.

|

|

|

Parry and Parry adopt the Weberian approach. They define professionals by their strong market situation. Professionals have the ability to obtain higher remuneration for their services than others. They do this primarily by erecting barriers to entry to the profession. This enables Parry and Parry to distinguish true professional groupings from those that only appear to be professional. For example, teachers are not really professionals because they do not have control over their market situation. Doctors have the British Medical Association to protect them, and they have established a monopoly over the practice of medicine. Teachers did not create a professional association before the state took over control of education.

|

|

|

Weberians do not agree that the position of any class should be defined in terms of its relation to capitalism and the way in which it serves the bougeoisie. They seek to understand the professional-managerial class in terms of their market situation and other factors. David Lockwood adopts a Weberian perspective, and analyses class situation in terms of three factors — (a) market situation — earnings, benefits, job security and promotion prospects; (b) work situation — degree of supervision and autonomy, relations with superior; (c) status situation — level of prestige attached to the work the individual does. Lockwood agrees that wage rates for clerical workers began to fall below those of manual workers from the 1930s onwards; however, he maintains that on other dimensions clerical workers still enjoy privileges that manual workers do not. He also opposes the view that clerical work has been deskilled.

|

|

The Proletarianisation thesis |

|

The proletarianisation thesis is advanced by Braverman. He maintains that many white-collar jobs have become less professional as a result of deskilling. The work of draftsmen, technicians, engineers, accountants, nurses and teachers has become more and more routine; these groups have lost their professional status. Braverman states that “male clerks and shop workers are now firmly among the broad mass of ordinary labour; and indeed often well down towards the bottom of the pile.” Service workers have also become deskilled — “the demand for the all-round grocery clerk, fruitier and vegetable dealer, dairyman, butcher, and so forth, has long ago been replaced by a labor configuration in the supermarkets which calls for truck unloaders, shelf stockers, checkout clerks, meat wrappers, and meat cutters; of these only the last retain any semblance of skill, and none require any general knowledge of retail trade.” The skills these people require is often no more than basic numeracy and literacy.

|

|

|

Some sociologists do not agree that the life-chances of clerks are limited. Steward, Prandy and Blackburn argue that most people who start work as clerks do not end up as clerks. For example, only 19% of those who start as clerks are doing clerical work by the age of 30; 51% by this age have been promoted to other non-clerical positions. So becoming a clerk is a stage in a career and not a final destination. Thus, clerks can be considered members of the middle class despite the routine nature of their work, because their final destination is different from that of manual workers, who do not have such career prospects.

|

|

|

However, Crompton and Jones have specifically attacked the work of Steward, Prandy and Blackburn through their study of 887 white-collar employees employed by either a local authority, a life assurance company or a major bank. Their criticisms are (a) that Steward, Prandy and Blackburn fail to deal with the position of female white-collar workers, who have minimal career prospects; (b) that the upward mobility of male clerks is exaggerated by firstly the fact that many clerks (30%) simply leave this kind of work and secondly by the fact that the boom in the expansion of managerial posts will come to an end; (c) that many managerial posts have themselves become deskilled and proletarianised.

|

|

|

Introduction of computerisation is correlated with deskilling. The more computers, the less skill is required of the employee.

|

|

The Structure of the middle-class |

|

So there is no agreement among sociologists regarding the structure of the middle class. Anthony Giddens regards the middle class as a single group defined by the “possession of educational or technical qualifications” who provide mental labour power; they are not members of the upper classes because they do not own the means of production. Goldthorpe redefines the middle class as the intermediate class and also redefines the ruling class as the service class, which includes large property owners, administrators, managers and professionals. Goldthorpe is effectively denying the Marxist interpretation of society, and making a broad distinction between two kinds of middle class rather than between the middle class (or proletariat) on the one hand and the bougeoisie on the other.

|

|

|

According to Roberts, Cook, Clark and Semeonoff the middle class is much more stratified than either of the two analyses above would suggest. In their 1972 survey of 243 male white-collar workers they found four distinct beliefs. Firstly, 27% of the sample held what they called a middle mass image of society; they thought they were members of a class that made up the majority of society sandwiched between a very small upper class, and a lower class that is decreasing in size. Secondly, 19% of the sample held a belief that they called the compressed middle class. This is the view that the middle class forms a narrow band of workers between the upper class and a large working class. Thirdly, 15% of the sample interpreted society as comprising a finely graded ladder of economic positions. Fourthly, 14% had a proletarian image of society, and regarded themselves as belonging to the working class.

|

|

|

Some sociologists believe that there has been further polarisation of society, with the upper section of the middle class moving closer to the bourgeoisie and the lower section become more proletarian. This view is adopted by Abercrombie and Urry.

|

|

|

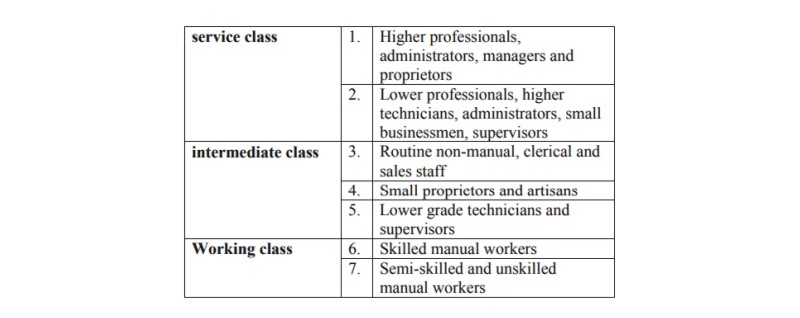

As examples of the functionalist approach, based mainly on occupational categories, Goldthorpe, following Lockwood, identifies three classes, with seven subdivisions in all, as follows:

|

|

|

|

Goldthrope — occupational categories

|

|

|

This categorisation ignores the existence of the bourgeoisie, by lumping together proprietors with higher professionals. The theoretical basis of the scheme is vague. It makes no provision for the separate status of women. It effectively treats everyone as middle class who is not working class, where working class is defined in terms of manual work.

|

|

The working class |

|

The working classes are generally regarded as comprising manual workers. Their economic, market situation is usually regarded as inferior to that of non-manual workers because (a) their earnings are, on average, lower than those of non-manual workers; (b) their wages usually reach a peak in their early thirties and thereafter decline, whereas the wages of non-manual workers usually increase throughout their career; (c) manual workers have less job-security than non-manual workers; (d) manual workers have fewer fringe benefits than non-manual workers.

|

|

|

For these reasons, statistical studies show that manual workers are more likely to die younger and suffer from poor health than non-manual workers. They are less likely to own their own homes. They are more likely to be convicted of criminal offences.

|

|

|

As a point of reference, sociologists tend to identify a stereotyped member of the working classes. Lockwood calls this the proletarian traditionalist. This typical member of the working classes is pictured to be employed in an industry employing large quantities of manual labour, such as mining, shipbuilding or docking; the working-class community they live in is dominated by a single occupational group. This means that workers live close to each other and there is very little geographical or social mobility; their aim is not to gain promotion or run their own businesses; they believe in collective goals. Their leisure pursuits are orientated towards immediate gratification and pleasure seeking, they “take life as it comes”. The proletarian traditionalist believes that society is sharply polarised into “us” and “them”, and accept a power model of society — namely that the bosses control society and the workers are relatively powerless to prevent this. This defines the sub-culture of the proletarian traditionalist.

|

|

|

The middle-class subculture is regarded as adopting a purposive approach. Middle class people are orientated towards future-time and they work for deferred gratification. The middle classes tend to adopt a status or prestige model of society — namely, that society is divided into many, many gradations of economic and social status, and it is possible to rise up this “ladder”.

|

|

|

Once again the effect of deindustrialisation must be considered: owing to deindustrialisation, there has been a general shift in the proportion of those working in manual jobs to those working in non-manual jobs.

|

|

Embourgeoisement |

|

The embourgeoisement thesis is that manual workers are increasingly entering the middle-classes and adopting middle-class attitudes. For example, highly paid affluent workers are becoming typical of manual workers. Their lifestyle and attitudes are not traditional proletarian and they are orientated towards acquisition of private property and the consumption of goods. This thesis is advanced by Jessie Bernard, who states that “The “proletariat” has not absorbed the middle class but rather the other way round ... in the sense that the class structure here describes reflects modern technology. It vindicates the Marxist thesis that social organization is “determined” by technological forces.”

|

|

|

The embougeoisement thesis has not been strongly supported by sociological studies. For example, Godthorpe, Lockwood, Bechhofer and Platt”s study (1963 to 1964), The Affluent Work in the Class Structure was based on a sample of 229 manual workers and 54 white-collar workers in Luton. They were employees of Vauxhall Motors, Skefko Ball Bearning Company and Laporte Chemicals. Just under half of these workers had migrated to Luton in search of well-paid employment. Their wages compared well to those of many white-collar workers. They were all married and 57% owned their own home.

|

|

|

The study showed that these workers had an instrumental orientation towards work — that is, they did not enjoy their work and regarded it as a means to making money. They regard trade unions as important for the purpose of collective bargaining, but join trade unions not out of class or social solidarity, but from principles of rational self-interest — namely, because collective bargaining can improve their individual pay and conditions. The soldaristic collectivism of the traditional worker is thus replaced by instrumental collectivism by the affluent worker. These workers are keen to achieve promotion to a white-collar job, and they accept that they should work hard for the firm in order to earn such opportunities.

|

|

|

Goldthorpe, Lockwood et al did not discover evidence that affluent workers adopted middle-class lifestyles in their private and family lives. They follow the traditional mould in their formation of friends, which are drawn from their wider families and neighbours. White-collar workers associate more with colleagues from work. However, the affluent worker is more home-centred than the traditional worker, and this is something he shares on common with the white-collar worker. Despite this, Goldthorpe, Lockwood et al maintain that affluent workers have no desire to become middle-class. The study also indicated that affluent workers are not more inclined to vote for the Conservative Party, and 80% of them still voted Labour.

|

|

|

Yet, unlike the traditional worker, they believe that their own actions can alter their destiny, and do not attribute their situation to fate. They hold the money model of society rather than power model of traditional workers or the prestige model of the middle classes. That is, they regard money as the basis of the division between the classes.

|

|

|

Goldthorpe, Lockwood et al conclude that the affluent worker is not being assimilated into the middle class, but propose instead that they are forming a new working class, which has some points of normative convergence with the middle class, meaning, some similarities of attitude, but no common identity.

|

|

|

Stephen Hill”s study of London dockers, conducted during the 1970s, provides further evidence for the emergence and growth of a working class with an instrumental attitude to work. The 139 dockworkers that he interviewed had very similar attitudes to those expressed by the Luton workers in the Goldthorpe et al study. Their aim was to improve their livings standards and they adopted an instrumental attitude to work. They were family centred and only 23% saw their fellow workers outside of work. They also looked on unions as instruments to achieving higher pay, and held a money model of society. However, Hill concludes that the “evidence of dock workers strongly suggests that the working class is more homogeneous than has been allowed for: those who wish to divide it into old and new greatly exaggerate the divisions which actually occur within the ranks of semi-skilled and unskilled workers.” The reason why he draws this conclusion is that the dockers might be expected to hold traditionalist views. It may well be that the whole manual working class has moved away from the views of the traditional proletarian and evolved into the instrumental, privatized worker.

|

|

|

Fiona Devine conducted a further study of affluent Luton workers between July 1986 and July 1987; her sample comprised 30 male manual workers from the shop floor of the Vauxhall car plant, and their wives. Her conclusion was opposed to that of Goldthorpe et al, and she did not believe that a new working class was emerging. In agreement with Goldthorpe et al she found some evidence of mobility, some instrumental attitudes to work and that the workers did not go to working men”s clubs, but tended to be more home centred, though not exclusively. She noted that these workers did not tend to make friends with members of the middle class, and she found evidence of declining support for the Labour Party. She concludes, “The interviewees were not singularly instrumental in their motives for mobility or in their orientations to work. Nor did they lead exclusively privatized styles of life. Their aspirations and social perspectives were not entirely individualistic. Lastly, the interviewees were critical of the trades unions and the Labour Party, but not for the reasons identified by the Luton team [of Goldthorpe et al.].”

|

|

|

Marx predicted that there would be increasing polarisation of society, and that the proletariat would become increasingly homogeneous (the same). However, Ralf Darendorf argues that the manual working class is becoming more and more differentiated, heterogeneous, this partly as a response to the introduction of computers. His thesis is that the C20th has seen a decomposition of labour — by which he means, a fragmentation of the manual working class. However, he is opposed by Roger Penn, who argues that there have always existed different levels of skill in the manual working class, a conclusion that he supports by means of his study of the cotton and engineering industries of Rochdale between 1856 and 1964. In other words, the manual working class is not more divided in the C20th than it was in the C19th.

|

|

|

Ivor Crewe supports the thesis that there is a new working class in Britain. He argues that members of this class tend to (a) live in the South of Britain; (b) be members of unions; (c) by employed by private industries and (d) own their own homes. This is in contrast to the old working class that tend to (a) live in the North of Britain; (b) be members of unions; (c) be employed directly or indirectly by the government and (d) live in council houses.

|

|

|

According to Marxist theory the proletariat will eventually develop class-consciousness. This means that individual members of the proletariat will come consciously to understand that they share a common economic situation, share common interests and are exploited by the bourgeoisie. This will lead in time to an awareness that by only by collective action can they achieve a just society, at which point the proletariat will become a class for itself. The question is to what extended members of the working classes in Britain share class-consciousness.

|

|

|

The traditional proletarian is the conception of a working class man who holds a power model of society. This means he sees society as divided into two classes, and uses the terms, “us” and “them” to describe them. This implies that the traditional proletarian has a form of class-consciousness. However, affluent workers predominantly adopt a money model of society, and believe that the gradations of society are necessary, and that they can improve their position by work. So such workers do not have class-consciousness. So if more workers are moving from the traditional proletarian position to that of affluent worker, then there is a reduction in working class-consciousness taking place, and class conflict is society is also decreasing. However, the claim that affluent workers are adopting decidedly functionalist interpretations of their economic situation is disputed, for example, by Fiona Devine who believes that the Luton workers that she studied hoped for “a more equitable distribution of resources in society as it stood, and, by implication, a more equal, free and democratic society in which people would be more justly and fairly rewarded than at present.”

|

|

|

It is also possible to argue that manual workers do not possess a coherent and consistent interpretation of society. This view has been advanced by Blackburn and Mann as a consequence of their 1970-1 study of unskilled manual workers in Peterborough. Hill also found inconsistencies in the beliefs of the London dockers that he studied.

|

|

Marx”s view of the underclass |

|

It is maintained by some sociologists that there exists an underclass — a group of people who occupy the lowest position in the social order, below that of the unskilled manual working class. Marx also wrote of an underclass, using the term lumpenproletariat he describes them as “The scum of the depraved elements of all classes ... decayed roués... vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazzaroni, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers ... brothel keepers ... tinkers, beggars ... the dangerous class, the social scum, that passively rotting mass thrown off by the lowest layers of the old society.” He also calls this group the reserve army of labour, and it is as a reserve that they are useful to the bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie use them to curb the power of the proletariat. Marx explains that “The industrial reserve army, during periods of stagnation and average prosperity, weighs down the active army of workers; during the periods of over-production and feverish activity, it puts a curb on their pretensions.” Here the underclass is equated with the unemployed, and Marx maintains that during a recession the unemployed serve the interests of the bourgeoisie since their existence frightens those who have work into accepting lower wages. During a boom, the unemployed soak up the newly created jobs, and once again force wages down. The economic power of the proletariat is thus reduced by the existence of the underclass, and so is their political power, since economic power is the basis of political power (for a Marxist).

|

|

|

Marx also used the term relative surplus population to describe those who occupy the lowest position in the social order. According to him this group was subdivided into (a) the floating surplus population, who are young people who are employed as cheap labour until they are adults, when they are replaced by other young people; (b) latent surplus population who are agricultural workers migrating to cities; (c) the stagnant population, who are people with irregular employment, and (d) paupers, whom he also calls “the actual lumpenproletariat”, comprising criminals, vagabonds, prostitutes, orphans, paupers, invalids, the old, widows, and so forth. This is a C19th view of the underclass. Marx was critical of this class because he did not believe it was capable of class consciousness and concerted political action.

|

|

Modern interpretations of the underclass |

|

American sociologist Charles Murray, in Losing Ground (1984) introduced the term underclass into modern sociology and claimed that America had a growing underclass. He also claimed that Britain has a growing underclass. However, he defines the underclass in terms of a culture of poverty rather than in terms of an economic position. He writes that the underclass are “defined by their behaviour. Their homes were littered and unkempt. The men in the family were unable to hold a job for more than a few weeks at a time. Drunkenness was common. The children grew up ill-schooled and ill-behaved and contributed a disproportionate share to the local juvenile delinquents.” This goes with the philosophy of blaming the poor for being poor, and adds little to an understanding of social stratification. His view is shared by Ralf Dahrendorf, who also characterises the underclass in terms of their sub-culture, which “includes a lifestyle of laid-back sloppiness, association in changing groups of gangs, congregation around discos or the like, hostility to middle class society, peculiar habits of dress, of hairstyle, often drugs or at least alcohol — a style in other words which has little in common with the values of the work society around.” Yet Dahrendorf at least makes some analysis of the economic causes of the existence of this group, claiming that technology has created surplus labour, and explaining that members of the underclass do not adopt the lifestyle of other citizens because they lack an economic stake in society and are provided with few benefits from society.

|

|

|

But who are the underclass? Since Murray and Dahrendorf answer this question in terms of behaviour, it is unclear who they think belongs to this group. One answer to this question is put forward by British Labour MP Frank Field. He claimed that poverty is increasing in Britain, and that there is a growing underclass made up of (1) the long-term unemployed, (2) single-parent families; (3) elderly pensioners. This group are characterized by being reliant on state benefits that are too low to give them an acceptable living-standard, and have no chance of escaping from reliance on state-benefits. Runicman also defines the underclass in this way, as “those members of British society whose roles place them more or less permanently at the economic level where benefits are paid by the state to those unable to participate in the labour market at all.”

|

|

|

Another sociologist seeking an economic explanation of the existence of the underclass is Anthony Giddens. He claims that the labour market is segmented (it is a dual labour market). In the primary sector jobs have “high and stable ... levels of economic returns.” in the secondary labour market they have “a low rate of economic return, poor job security”. Women and ethnic minorities are more likely to be included in the secondary labour market. However, Kirk Mann criticises Giddens for producing scant evidence for the segmentation of the labour market in the way Giddens describes. Additionally, racism and patriarchy are, in his view, the main causes for why women and ethnic minorities have poorer economic opportunities — it is not the market itself that determines these.

|

|

Neo-Marxist analysis of class |

|

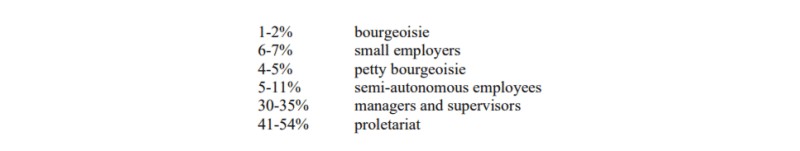

Erik Olin Wright is an American neo-Marxist. He analyzed the American class structure as follows: (a) bourgeoisie who own sufficient capital to work for themselves but not to hire others; (b) petty bourgeoisie, with some control over production and some investments; (c) the proletariat. However, there is a strata sandwiched between the bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie of small employers; these are people who employ other workers but also work in their own business. Between the proletariat and the petty bourgeoisie there is a strata of (d) semi-autonomous wage-earners. There is also a class of (e) managers and supervisors. Wright estimated that in the USA in 1969 there were

|

|

|

|

|

However, Wright has subsequently developed a new typology of the class system in a capitalist society, dividing society into those who own the means of production and those who do not; within the former category fall the bourgeoisie, small employers and petty bourgeoisie; within the latter category fall the other groups, now subdivided into nine sub-strata according to their skills and status within an organization. This approach is criticised by other Marxists as representing a departure from Marxism, since skills and organizational status are used to analyse class position, and these are not aspects purely of the relationship to capital — Marx analyses class purely in terms of the ownership of capital. The category of semi-autonomous employees has also been criticized for being too vague, and encompassing a strange mixture of different occupations, from miners to computer programmers.

|

|

|

Runciman basis his analysis of class on the concept of a role. Most people have occupational roles. Most people have occupational roles, but some do not. For example, non-working wives do not. Such people are treated as having the same occupational role as their spouses. He also identifies three source of economic power (1) ownership of the means of production; (2) managerial control of production; (3) marketable skills. A person”s class is an amalgam of all three sources of economic power.

|

|

|

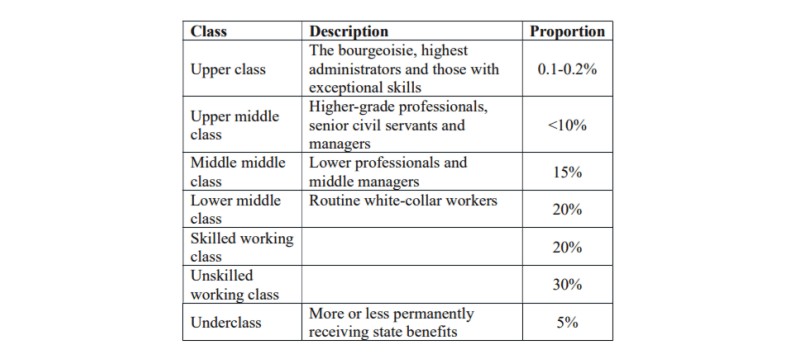

On this basis, Runciman identifies seven classes:

|

|

|

|

Runciman's seven classes

|

|

Marxist interpretation of power in modern Britain |

|

Westergaard and Resler (1975) defend the Marxist interpretation of the distribution of power in modern Britain, arguing that there is a ruling class in Britain. They claim that power is based on wealth, and point to the continued existence of the uneven distribution of wealth in Britain to defend their thesis. In their view, the ruling class comprises 5 to 10% of the population, and incorporates directors, top executives and share-holders.

|

|

|

This interpretation is rejected by Peter Saunders. He acknowledges that “a few thousand individuals at most are today responsible for taking the bulk of the key financial and administrative decisions which shape the future development of British industry and banking, but he claims that the power these individuals have derives from their position within large companies and not from their ownership of wealth. Saunders also believes that modern capitalism is responsible for redistributing wealth and power more widely.

|

|

|

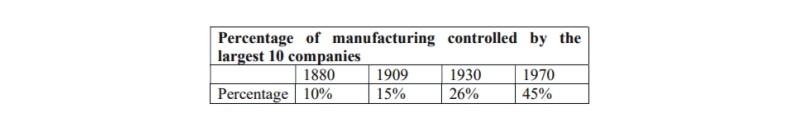

John Scott has provided an in-depth analysis of power in Britain. In his view in Britain during the C19th the upper classes were divided into three — the landowners, the manufacturers and the financiers. During the century these three groups fused into a single class. Initially, the industrial revolution created the groups of nouveau riche — the industrialists and financiers, and power shifted from land to industry. However, as industry became increasingly dominated by large-scale manufacturers, so the three sections of the upper classes came closer together; the fusion of these groups into a single class occurred during the inter-war period (1919 — 1939). Scott”s estimates of the percentage of manufacturing controlled by the largest ten companies in Britain are as follows

|

|

|

|

|

Scott agues that ownership of small numbers of shares does not make one a capitalist. To be a capitalist you must have substantial wealth. He also acknowledges that membership of the upper end of the service class may enable one to enter the capitalist class. “Those who hold directorships in large enterprises occupy capitalist locations, and if the income from employment is substantial they may be able to sustain a relatively secure foothold in the capitalist class.” However, membership of the service class does not automatically mean that you will be able to join the capitalist class. If you win your position late in your career you may not have sufficient time to accumulate the wealth necessary to count yourself a member of this class; likewise, most members of the service class are only retained for as long as they are useful to the capitalist class. In further support of his thesis, Scott points out that in 1988 there were 290 people holding directorships on the boards of two or more of the top 250 companies. All in all he claims that about 0.1% of the population comprise the ruling elite, about 45,000 individuals, with a minimum wealth of £740,000 each. These people controlled 7% of the wealth of the land. The top 200 families had assets in excess of £50m each.

|

|

|

Scott defines a power bloc to be a group of people who have established a monopoly over political power. The civil service elite is subject to this power bloc, and civil service positions tend to be recruited from members of the capitalist class via public schools. It is not true that recruitment into the top echelons of the civil service is exclusively monopolised by people with public school backgrounds, but there is a strong bias in this direction nonetheless. Government policy is strongly influenced by the financiers of the City of London, who are capitalists.

|

|